You’ve done it. You’ve worked hard, saved up, and finally bought that shiny new gadget, that designer bag, or even that slightly-too-expensive car. For a moment, a fleeting, glorious moment, you feel it: a surge of satisfaction, perhaps even pride. But then, as quickly as it arrived, the feeling begins to fade, replaced by a subtle unease, a yearning for the next thing, the better thing, the thing that will truly impress.

Why do we chase these ephemeral highs? Why do we spend money we often don’t truly have, on things we don’t truly need, to impress people we don’t truly like? Is it simply personal preference, or something far more insidious, deeply embedded in the fabric of society and even our ancient biology?

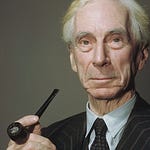

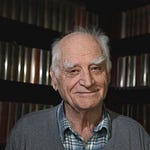

Enter Thorstein Veblen, a Norwegian-American economist and sociologist from the turn of the 20th century, whose groundbreaking work, “The Theory of the Leisure Class”, ripped open the polite veneer of modern society to expose the raw, often irrational, drive for status that fuels our consumption habits. He argued that much of our economic activity isn’t about utility, but about something far more primitive and powerful: showing off.

The Echoes of the Primitive

Before Veblen, classical economics assumed humans were rational actors, making choices based on maximizing utility. Veblen saw a different picture. He looked back at tribal societies, where status was earned through prowess in hunting or warfare. The most successful warrior wasn’t just admired; his success signaled strength, fertility, and desirability.

As societies evolved, Veblen posited, this display of prowess didn’t disappear; it merely transformed. With the rise of private property, the battleground shifted from the hunt to the marketplace. Status was no longer about demonstrating physical might, but about displaying one’s ability to accumulate and, crucially, to waste wealth. This is where “conspicuous consumption” was born.

Conspicuous Consumption: The Ultimate Flex

Think about it. Why buy a luxury watch when a simple one tells time just as well? Why a designer handbag when a practical one carries your essentials? Veblen observed that the true value of many goods in a “leisure class” society wasn’t their functional utility, but their ability to signal wealth. The more expensive, the more exclusive, the more obviously unnecessary a possession, the better it served its purpose.

This isn’t just about showing off; it’s a deep-seated, almost primitive evolutionary signal. By purchasing an outrageously expensive car or wearing a ridiculously priced item, you are, in essence, broadcasting: “I have so much surplus wealth that I can afford to waste it on something utterly non-essential. I am so secure in my resources that I don’t need to be practical.” This act of waste, Veblen argued, is a powerful, albeit often unconscious, signal of power and social standing.

In order to gain and to hold the esteem of men it is not sufficient merely to possess wealth or power. The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence.

— Thorstein Veblen

This “conspicuous consumption” becomes a trap. We’re locked into a cycle of acquiring goods not for their inherent value, but for their symbolic message. It’s an arms race of acquisition, driven by the need to constantly out-signal or keep pace with our peers.

Conspicuous Leisure: The Art of Doing Nothing Expensively

But it’s not just about what you buy; it’s also about what you *don’t* do. Veblen also introduced “conspicuous leisure” – the non-productive consumption of time. Imagine a person who spends years mastering an obscure ancient language, or an expensive sport like polo or yachting. These activities offer no practical return; their value lies precisely in their lack of utility, signifying that the individual is so wealthy they don’t need to engage in productive labor.

A personal assistant, a house staff, or even lengthy, exotic vacations are all forms of conspicuous leisure. They signal that one’s time is too valuable to be spent on mundane tasks, or that one has the freedom from necessity to dedicate significant time to non-remunerative pursuits. It’s a subtle, yet potent, display of economic power.

The Rat Race of Emulation

Perhaps Veblen’s most devastating insight was “pecuniary emulation.” He argued that the leisure class sets the standard for status, and everyone else attempts to imitate them. The working class emulates the middle class, the middle class emulates the upper-middle class, and so on. This creates a relentless, cascading desire that trickles down through all layers of society.

No matter where you stand on the economic ladder, there’s always someone above you whose consumption habits you aspire to, whose lifestyle you secretly envy. This constant striving means true contentment is always out of reach, perpetually deferred to the next purchase, the next status symbol. It’s an endless treadmill, fueled by the primal urge to belong and to be admired.

The incentive that lies at the root of ownership is the desire to excel, it is emulation.

— Thorstein Veblen

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

The Iron Cage of Status

Veblen’s ideas resonate with chilling accuracy in our modern world. Social media, with its curated highlight reels and performative lifestyles, has become the ultimate stage for conspicuous consumption and leisure. Every post, every story, every shared experience can be an unwitting act of status signaling, designed to elicit envy or admiration.

This insidious drive for status, deeply embedded in our psychology and amplified by societal structures, keeps us running on a treadmill of acquisition, never truly reaching a finish line.

We are addicted to status because, from an evolutionary standpoint, it once signaled survival and reproductive success. Today, it signals worth in a pecuniary culture. But at what cost? To our wallets? To our mental well-being? To the planet, as we perpetually consume and discard in this endless chase?

Veblen’s work is a stark reminder that our desires are often not our own, but rather echoes of ancient drives warped by modern economic structures. It challenges us to look beyond the surface of our purchases and question the true motives behind our striving. Are we buying what we need, or are we simply performing a ritual of status, trapped in a cycle designed to keep us wanting more?

Perhaps understanding this addiction is the first step towards breaking free, towards valuing utility over display, and finding contentment not in what we own, but in who we are and what we genuinely contribute.