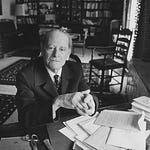

We live our lives on a stage, perpetually curating a self for an unseen audience. Every purchase, every vacation photo, every carefully chosen word feels like a line in a script we didn’t write but are compelled to perform. This suffocating sense of being watched and judged is not a modern invention of the digital age. It is a fundamental human trap, one diagnosed with chilling precision over a century ago by the economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929). In his seminal work, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Veblen revealed that our economic lives are driven less by need and more by a desperate, theatrical performance of status—a performance that has now become our reality.

We are so accustomed to disguise ourselves to others that in the end we become disguised to ourselves.

François de La Rochefoucauld

Veblen posited that individuals engage in ostentatious displays of wealth and leisure not merely to satisfy survival needs, but primarily to demonstrate social status and economic power. His insights laid the groundwork for a critical understanding of economic behavior as a socially constructed phenomenon, shaped by cultural norms and class distinctions, rather than purely utilitarian needs. His concept of conspicuous consumption describes how consumers are driven by a desire to signal wealth through the acquisition of luxury goods, which serves to reinforce social hierarchies and class distinctions. This behavior is particularly pronounced in capitalist societies, where social stratification is often reflected through ownership and display of material possessions. Veblen’s theories extend beyond consumer goods to encompass the notion of conspicuous leisure—activities performed for their social signaling value rather than their utility—illustrating how leisure itself can become a status symbol within stratified societies.