Picture a world where the loudest voices are not the wisest, where expertise is met with suspicion, and where the most common opinion becomes the most celebrated truth. Imagine a society not just tolerant of mediocrity, but actively demanding it, even imposing it, as the prevailing standard. Does this feel uncomfortably familiar? It should, because over ninety years ago, a Spanish philosopher saw this future unfolding and issued a stark, prophetic warning.

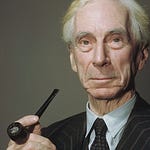

That philosopher was José Ortega y Gasset, and his monumental work, “The Revolt of the Masses” (1930), was less a sociological study and more a passionate, almost despairing, cry against what he perceived as a burgeoning crisis of civilization. Ortega didn’t just predict the rise of a new type of human; he anatomized it, revealing a dangerous psychological and cultural shift that continues to echo in our modern world.

Who is this “mass man” Ortega warned us about? And why, in an age of unprecedented access to information and opportunity, does his militant mediocrity pose such a profound threat?

The Birth of the Mass Man

To understand Ortega’s “mass man,” we must first grasp the context of his time. The early 20th century witnessed an explosion of population, industrialization, and democratic ideals. More people than ever before were entering public life, participating in the political process, and enjoying material comforts previously reserved for a select few. This was, in many ways, a triumph of progress.

But Ortega saw a shadow creeping across this bright landscape. He wasn’t speaking of a social class, like the proletariat or the aristocracy, but a psychological type that could emerge from any stratum of society. The mass man, for Ortega, was not the uneducated laborer, but rather anyone who, “feeling himself ‘just like everybody,’ is not in the least concerned about it; on the contrary, he feels at home in recognizing himself as identical with everybody else.”

He is the individual who accepts the world’s abundance as a given, without questioning its origins or the effort required to maintain it. He lives in a state of “radical ingratitude,” oblivious to the complex structures and historical struggles that made his comfortable existence possible.

The Anatomy of Militant Mediocrity

What defines this new human type? The mass man is characterized by a disturbing blend of entitlement and intellectual sloth. He doesn’t strive for excellence or challenge himself; instead, he is content to drift, to conform, and to assert his opinions without the burden of deeper thought or personal responsibility.

Consider these core traits:

Unquestioning Entitlement: The mass man believes he has a right to everything, simply by existing. He views society’s advancements as natural phenomena, not as the result of immense effort, sacrifice, and specialized knowledge.

The Demand for Rights Without Obligations: This is perhaps Ortega’s most piercing insight. The mass man asserts his demands, his desires, his “rights” with an unprecedented vigor, yet feels absolutely no corresponding obligation or duty to society, to tradition, or even to the pursuit of self-improvement.

Intellectual Arrogance in Ignorance: Here lies the true danger. The mass man not only ignores complex ideas or specialized knowledge; he actively resents them. He dismisses those who dedicate themselves to mastery as elitist or irrelevant. He celebrates his own ignorance as a form of authenticity, elevating “common sense” — no matter how poorly informed — above expertise and rigorous thought.

Imitation and Conformity: Paradoxically, despite his assertion of individual rights, the mass man finds comfort in being “like everyone else.” His opinions are often borrowed, his tastes dictated by the collective, and his worldview shaped by the prevailing currents, rather than independent reflection.

Does this sound like a familiar character in our digital age, where opinions are instantly shared, often unverified, and where echo chambers reinforce preconceived notions?

The Militancy of the Mediocre

Ortega’s central warning was not merely that the mass man exists, but that he has begun to dominate. This isn’t a passive phenomenon; it’s an active “revolt.” The mass man, filled with an “indocile temper,” feels empowered to impose his own mediocre ideas and values upon society.

He doesn’t tolerate dissenting opinions or superior intellect; he silences them. He doesn’t engage in nuanced debate; he asserts his viewpoint as definitive. When reason or expertise stands in his way, he resorts to what Ortega called “direct action”—a crude, impatient assertion of will over argument. This can manifest as an unwillingness to listen, a dismissal of facts, or an aggressive rejection of any authority beyond his own unexamined prejudices.

The greatest danger, Ortega warned, lay not just in the existence of such individuals, but in their aggressive insistence that their mediocrity be the societal standard, demanding rights without obligations and celebrating ignorance as a virtue.

The mass crushes beneath it everything that is different, everything that is excellent, individual, qualified and select. Anybody who is not like everybody, who does not think like everybody, runs the risk of being eliminated.

— José Ortega y Gasset

A World Without “Why”

The implications of this militant mediocrity are profound. When the mass man comes to power, whether politically or culturally, society begins to unravel. Innovation falters, because true progress requires specialized knowledge and dedicated effort. Institutions designed to foster intellectual growth and critical thinking are undermined, their value questioned by those who see no need for them.

Democracy itself, meant to be a system of reasoned debate and responsible participation, risks devolving into a tyranny of the unqualified majority. When everyone’s opinion is deemed equally valid, regardless of knowledge or experience, the pursuit of truth and the recognition of excellence become casualties.

The mass man is he whose life has no purpose, and who is consequently a danger to himself and to others.

— José Ortega y Gasset

Ortega saw a society losing its “why”—losing its sense of purpose, its drive for betterment, its respect for the intricate complexities of civilization. It becomes a society focused solely on consumption and gratification, devoid of the self-imposed obligations that drive true progress and cultural flourishing.

Navigating the Era of the Average

So, what can be done? Ortega’s work is not a call for a return to aristocratic rule, nor a dismissal of democratic ideals. Rather, it is an urgent plea for individual responsibility and intellectual rigor. The antidote to the “mass man” lies not in changing others, but in cultivating the “select minority” within ourselves and encouraging it in those around us.

This means:

Embracing Self-Demand: Consciously choosing to live a life of effort, striving for excellence in our chosen fields, and engaging in continuous learning, even when it’s difficult.

Cultivating Intellectual Humility: Recognizing the limits of our own knowledge and being open to expertise, different perspectives, and the complexities of the world.

Valuing Obligations: Understanding that true freedom comes with responsibility, and that our “rights” are often built upon the duties and sacrifices of others, and require our own reciprocal contributions.

Protecting Spaces for Excellence: Supporting institutions, conversations, and individuals who champion critical thinking, nuanced debate, and the pursuit of mastery, even if it goes against the popular tide.

The battle Ortega described is an invisible war for standards, for depth, and for the very soul of civilization. It is fought not with weapons, but with ideas, with habits of mind, and with the courage to demand more of ourselves than the comfortable path of least resistance.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

Ortega y Gasset’s “Revolt of the Masses” remains as relevant today as it was nearly a century ago, perhaps even more so. The “mass man” is not a relic of a bygone era; he is a pervasive presence in our hyper-connected, opinion-saturated world. His insistence on rights without obligations, his celebration of ignorance as virtue, and his aggressive dismissal of excellence pose a continuous threat to the delicate balance of a free and flourishing society.

His work serves as a powerful reminder that progress is not automatic, and that civilization is a fragile construct, constantly demanding the self-imposed obligations and intellectual rigor of individuals. The choice, as ever, lies with us: to drift on the currents of collective mediocrity, or to stand firm in the pursuit of a more thoughtful, responsible, and demanding way of being.