Imagine a grand, towering organization, a bustling hive of activity where brilliance is rewarded, and hard work recognized. Sounds ideal, doesn’t it? Now, picture a subtle, almost imperceptible force at play within this very structure, a silent algorithm diligently promoting individuals up the ladder, not towards greater achievement, but towards an inevitable, almost comical, state of inadequacy. For decades, we’ve chuckled at the idea, but what if this wasn’t just a cynical joke, but a fundamental truth about how our hierarchies actually function?

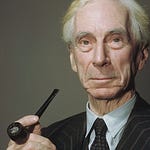

This is the unsettling revelation offered by Laurence J. Peter, a Canadian educator and management theorist whose name became synonymous with one of the most enduring observations in organizational psychology: the “Peter Principle.” It’s a concept so disarmingly simple, yet so profoundly disturbing, that once you see it, you start spotting it everywhere. What if the very mechanism designed to elevate the capable is, in fact, a carefully constructed pathway to universal incompetence?

The Ascent to Incompetence: A Universal Law?

The core of Peter’s startling argument, laid out with surgical precision in his 1969 book “The Peter Principle,” is deceptively straightforward: “In a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence.” Think about that for a moment. What does it truly mean?

Consider a competent salesperson. They excel, hitting targets, delighting customers. Naturally, they are promoted to sales manager. In their new role, the skills required change dramatically. It’s no longer about selling, but about leading, strategizing, motivating a team. If they prove competent as a manager, they might rise again, perhaps to regional director. But what if they struggle as a manager? What if they are excellent at selling but dreadful at managing? Their promotions stop. They have reached their “level of incompetence.”

The crucial insight is that individuals are promoted based on their performance in their current role, not necessarily their aptitude for the next. This seems logical, even fair. Yet, it creates a relentless upward current. The competent are elevated; the incompetent are left to languish in the positions where they can do the most harm – or at least, the least good – because they will not be promoted further.

Symptoms of a Systemic Flaw

The Peter Principle isn’t just an abstract theory; its effects are visible in every corner of our professional lives. Have you ever encountered a manager who seemed utterly overwhelmed, unable to make decisions, or a department head who actively obstructed progress without even realizing it? These aren’t necessarily lazy or malicious individuals; they are often the living embodiment of Peter’s observation.

Incompetence, once achieved, becomes a kind of organizational inertia. The individual, now at their ceiling, remains there, often supported by the very system that elevated them. They may develop elaborate coping mechanisms to mask their inadequacy, such as:

Percussive Sublimation: Also known as being “kicked upstairs,” where an individual is moved to a position of higher status but less responsibility, effectively removing them from a critical path without demoting them.

Creative Incompetence: Engaging in busywork or creating unnecessary committees to appear productive.

Rule-Following to a Fault: Adhering rigidly to procedures, even when they make no sense, as a substitute for actual leadership or problem-solving.

These are not flaws of character, but systemic outcomes. The system, by design, ensures that most positions above the lowest rung will eventually be occupied by someone who is no longer effective.

In a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence.

— Laurence J. Peter

The Mathematical Inevitability

What makes the Peter Principle so chillingly powerful is its almost mathematical certainty. It isn’t just about bad hires or poor judgment; it’s an inherent property of any hierarchical system where promotion is the primary reward for competence. If you keep promoting people who are good at X to do Y, eventually you’ll run out of people who are good at Y, and you’ll be left with people who are merely good at X (and now bad at Y).

Consider a large organization with many levels. At each level, individuals are promoted until they fail to perform adequately. Once they fail, their upward movement stops, and they remain in that position. Over time, all positions that are not at the very lowest level (where performance can always be improved upon) will tend to be filled by individuals who have reached their level of incompetence. The very success of a promotion system guarantees this outcome.

Perhaps the true genius of Peter’s observation lies not in its cynicism, but in its stark, unforgiving illumination of systemic flaws we often choose to ignore.

The job of a manager is to find what the problem is and then do nothing about it.

— Laurence J. Peter

Beyond the Principle: Navigating the Incompetent Universe

If incompetence is an organizational inevitability, are we doomed? Not necessarily. Understanding the Peter Principle is the first step towards mitigating its effects. For individuals, it encourages self-awareness. Is this next promotion truly a step forward into competence, or a leap into an abyss of inadequacy?

For organizations, the challenge is greater, requiring a re-evaluation of traditional promotion structures:

Separate Expertise from Management: Create parallel career tracks that reward technical or creative expertise without forcing individuals into management roles they’re unsuited for.

Train for the Next Role: Invest heavily in training and development for the prospective role, not just the current one, before promotion.

Focus on Skills, Not Just Performance: Evaluate candidates for promotion based on the specific skills required for the new position, not solely on their stellar performance in their current role.

Lateral Moves and Demotions: Create a culture where lateral moves are seen as development opportunities and demotions are not stigmatized but are pathways to finding a better fit.

The goal isn’t to abolish hierarchies, but to build more resilient ones that can identify and counteract the natural pull towards incompetence. It demands a shift from simply rewarding past success to strategically cultivating future capability.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

The Enduring Mirror

Laurence J. Peter’s work remains a brilliant, albeit discomforting, mirror reflecting the realities of our modern workplaces. He didn’t just coin a catchy phrase; he articulated a profound, systemic truth about human organization. His “mathematical reason” for incompetence isn’t an indictment of individuals, but a commentary on the structures we build. By understanding the Peter Principle, we gain not just a reason to chuckle, but a powerful lens through which to analyze, critique, and perhaps, even redesign the hierarchies that shape our world, striving for a future where competence, not incompetence, truly rules.