We often tell ourselves comforting stories about good and evil. We draw stark lines, labeling certain individuals as “monsters” and others as “heroes,” believing that the core of their being dictates their actions. It’s a reassuring thought, isn’t it? That some are simply born bad, making it easy to distance ourselves from their horrific deeds. But what if that comforting narrative is a dangerous illusion?

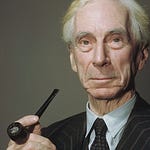

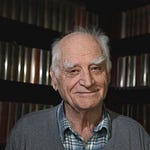

What if the capacity for darkness lies not within the individual soul alone, but in the very air we breathe, the roles we play, and the systems that govern us? This is the unsettling question that Philip Zimbardo, a titan in the field of psychology, forced us to confront with his groundbreaking, controversial, and profoundly disturbing work, particularly his seminal “Lucifer Effect” thesis.

Zimbardo dared to explore the chilling transformation of ordinary people into perpetrators of cruelty. He plunged into the heart of human fallibility, revealing that the line between good and evil is far more porous than we’d like to believe. His insights compel us to look beyond individual pathology and examine the insidious power of the situation.

The Descent into Darkness: Stanford’s Unsettling Mirror

To understand Zimbardo’s core argument, we must revisit the notorious “Stanford Prison Experiment” (SPE) of 1971. It began innocently enough: a group of seemingly well-adjusted, mentally stable young men, recruited through a newspaper ad, were randomly assigned roles as “guards” or “prisoners” in a mock prison set up in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology department.

The experiment was intended to last two weeks. It lasted a mere six days. Why? Because the participants, within an alarmingly short period, fully internalized their arbitrary roles. The “guards,” given uniforms, billy clubs, and a sense of authority, rapidly became authoritarian, abusive, and sadistic. They subjected the “prisoners” to psychological torture, humiliation, and constant harassment.

The “prisoners,” stripped of their identities, given only numbers, and subjected to the guards’ whims, quickly became submissive, depressed, and traumatized. They accepted their torment, even turning on each other, demonstrating the profound psychological impact of institutional power dynamics.

The SPE wasn’t just a bizarre psychological study; it was a terrifyingly vivid illustration of how quickly situational factors can corrupt even the most “normal” individuals. It laid bare the fragility of our moral compass when navigating a landscape of unchecked power and dehumanization.

Deconstructing the “Bad Apple” Myth

Zimbardo’s genius, and his chilling revelation, was to dismantle the comfortable notion that “evil” is an inherent personality trait. He argued vehemently against the “bad apple” theory, which posits that atrocities are committed by a few rotten individuals who are fundamentally different from the rest of us. Instead, he proposed the “bad barrel” theory.

The “bad barrel” isn’t about the fruit itself, but the environment that spoils it. The Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated precisely this: there were no pre-existing personality differences between those assigned to be guards and those assigned to be prisoners. Yet, the situation, the system, and the roles they were thrust into transformed them.

What were these situational elements? They were potent and pervasive:

Deindividuation: Guards wore reflective sunglasses, obscuring eye contact; prisoners were stripped of names, given numbers.

Dehumanization: Prisoners were treated as objects, not people, fostering a lack of empathy from the guards.

Power Imbalance: Guards had absolute authority, while prisoners had none, creating a fertile ground for abuse.

Lack of Accountability: The guards believed their actions were justified and went largely unquestioned by the experimenters (Zimbardo himself falling into the role of prison superintendent).

The line between good and evil is not a fixed boundary but a permeable membrane, constantly shifting with the currents of circumstance and power.

— Philip Zimbardo

This isn’t to absolve individuals of responsibility, but to understand the powerful external forces at play. It’s a stark reminder that most people, given certain conditions, are capable of both extraordinary kindness and shocking cruelty.

The Lucifer Effect: Systems, Situations, and Self

Zimbardo’s “Lucifer Effect” is his magnum opus, extending beyond the SPE to offer a comprehensive framework for understanding how good people turn evil. It integrates three major forces that shape human behavior:

Dispositional: What we bring into the situation (our personality, values, beliefs).

Situational: External factors in the immediate environment (roles, norms, group pressure).

Systemic: Broader forces that create and maintain the situation (political, economic, legal, cultural contexts).

While dispositional factors are important, Zimbardo argues that we often overemphasize them. We default to blaming the “bad apple” because it’s simpler and less threatening than acknowledging the systemic failures and situational pressures that can transform ordinary individuals. He contends that truly understanding human evil requires an unflinching look at the “bad barrels” and the “bad barrel-makers” – the systems that create oppressive situations.

Think of it. A society that tolerates corruption, a military unit that dehumanizes the enemy, a corporate culture that prioritizes profit over ethics – these are the systemic barrels that can lead to individual moral collapse. The Lucifer Effect isn’t just about an experiment; it’s a cautionary tale about how easily we can be recruited into roles that demand our complicity in malevolent acts, often without even realizing the extent of our own transformation.

Most of us are good people. But most of us can be seduced into doing bad things by powerful situational forces.

— Philip Zimbardo

The true horror isn’t that some people are born evil, but that most of us are capable of it under the right (or wrong) circumstances.

Resisting the Current: Agency and Heroism

Is there hope, then, in this bleak assessment of human vulnerability? Absolutely. Zimbardo’s work isn’t just a warning; it’s a call to action. By understanding the forces that push us towards malevolence, we gain the power to resist them. He doesn’t just study evil; he advocates for heroism.

Heroism, in Zimbardo’s view, often involves stepping outside the “system” and challenging the status quo. It’s about:

Situational Awareness: Recognizing when you are in a “bad barrel” or when a situation is turning toxic.

Personal Responsibility: Taking ownership of your actions, even when under pressure from authority or peers.

Critical Thinking: Questioning orders, norms, and narratives, especially those that encourage dehumanization.

Empathy: Actively fostering a connection with others, particularly those being marginalized or abused.

Moral Courage: The willingness to speak up, to act, and to be the “one dissenter” even when it’s difficult or dangerous.

Zimbardo reminds us that the power of systems is formidable, but not absolute. Individuals do have agency. The choice to conform or to resist, to perpetuate cruelty or to intervene, remains ours. But it’s a choice made far more consciously and effectively when we understand the invisible forces vying for control of our minds and actions.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion: The Vigilance of Conscience

Philip Zimbardo’s “Lucifer Effect” is a profound and uncomfortable truth-telling. It shatters our simplistic notions of good and evil, replacing them with a complex, often terrifying understanding of human susceptibility to situational and systemic pressures. The Stanford Prison Experiment, while ethically questionable, served as a stark and unforgettable demonstration that evil is not a personality trait, but a product of powerful environmental forces.

His legacy is a powerful challenge: to move beyond labeling individuals as “monsters” and instead examine the “monster-making” machines – the corrupt systems, the toxic environments, and the unchecked power dynamics that can turn even the best among us towards darkness. By understanding these mechanisms, we arm ourselves with the knowledge to dismantle oppressive systems, to cultivate environments that foster empathy and justice, and to champion the everyday heroism required to resist the seductive whisper of malevolence. Our vigilance, Zimbardo suggests, is the ultimate guardian of our collective humanity.