What if the most powerful legislator in any society is not a king, a parliament, or a constitution, but the very air we breathe and the soil beneath our feet? This was the radical proposition of Montesquieu, an Enlightenment thinker who argued that climate is the “first empire,” a silent, invisible force that shapes our passions, our character, and ultimately, the laws that govern us.

Long dismissed as a deterministic curiosity, his theory is now staging an unnerving comeback, forcing us to confront whether our legal systems are equipped to handle a world where the climate is no longer a stable backdrop, but a volatile and vengeful sovereign.

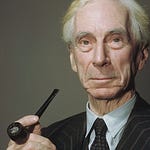

The Mind of the Theorist

Early Life and Education

Montesquieu, born in 1689, hailed from a noble family in France, which provided him with a solid educational foundation. His early exposure to various philosophical and political ideas shaped his intellectual trajectory. He studied law at the University of Bordeaux, where he developed a keen interest in the social sciences, particularly the relationship between laws, culture, and environment.

Influences on His Thought

Montesquieu’s philosophical outlook was profoundly influenced by prominent thinkers of his time, including John Locke, René Descartes, and Thomas Hobbes. These interactions enriched his understanding of governance, rights, and the nature of society, ultimately leading him to explore how environmental factors could shape human institutions.

His seminal work, The Spirit of the Laws, published in 1748, is a cornerstone of political philosophy, where he posits that laws are not universal but instead must be adapted to the specific circumstances of a society, including its climate and geography. This perspective marked a departure from the rigid determinism often attributed to him, suggesting a more nuanced view that recognizes the interplay between material conditions and human agency.

The Enlightenment Context

Montesquieu’s contributions occurred during the Enlightenment, a period characterized by a surge in rational thought and skepticism towards traditional authority. His work, particularly Persian Letters, not only reflects his critique of European society but also serves as a vehicle for examining broader themes of cultural relativism and human rights.

Through the lens of a Persian visitor to France, Montesquieu cleverly critiques the customs and norms of his own society, illustrating how cultural perceptions can shape understanding and governance.

By grounding his analysis in the relationship between climate, geography, and laws, Montesquieu laid the groundwork for later social theories and political philosophies, emphasizing the importance of contextual factors in shaping human behavior and societal structures.

An invasion of armies can be resisted, but not an idea whose time has come.

Victor Hugo

The Theoretical Framework: Law’s Natural Roots

Montesquieu’s work, particularly in The Spirit of the Laws, presents a foundational framework for understanding the intricate relationship between climate, law, and society. His exploration reveals that human laws and social institutions, which are created by fallible beings, cannot be divorced from the environmental contexts in which they exist. Montesquieu posits that laws are not merely the products of human ingenuity but are also influenced by the nature of the world and the climate within it. He asserts that “laws, in their most general signification, are the necessary relations arising from the nature of things,” implying a connection between the laws of society and the laws of nature, including climate considerations.

Climate and Legal Systems

The resurgence of interest in the intersection of climate and law stems from the pressing realities of climate change, which has underscored the urgency for legal frameworks that can effectively address environmental issues. Michaels emphasizes that this relationship is not merely scientific but inherently political, reflecting a shift from a focus on causal explanations to a recognition of the complexities and uncertainties involved in legal and environmental interactions. In this light, comparative lawyers are called to re-engage with the connections between law, society, and scientific understanding, taking cues from Montesquieu’s insights while acknowledging that contemporary contexts differ significantly from his time.

The Role of Comparative Law

In re-evaluating the entanglement of law and climate, comparative lawyers face the challenge of constructing new foundations that can bridge historical and modern perspectives. Michaels suggests that the current legal landscape reflects a re-entangled world, where climate considerations permeate legal thought and practice in ways that may not always be socially beneficial. The call for a nuanced interpretation of climate theory highlights the need for a legal understanding that embraces the dependency of human existence on climate and recognizes the socio-political dimensions of environmental issues. As such, the role of law extends beyond mere regulation; it must also incorporate ethical considerations regarding sustainability and equity, particularly for vulnerable populations such as indigenous communities who rely heavily on their climate for survival.

This theoretical framework thus underscores the critical need for a multidimensional approach to law that recognizes the significant influence of climate, urging contemporary legal scholars and practitioners to integrate these insights into their work.

The Argument: How Climate Writes the Law

Historical Context and Theoretical Foundations

The relationship between climate and law has a long-standing history, notably articulated by the philosopher Montesquieu in his seminal work, The Spirit of the Laws. Montesquieu posited that climate exerts a significant influence on the character and passions of individuals, which in turn shapes the laws governing societies. He argued that “if it is true that the character of the spirit and the passions of the heart are extremely different in the various climates, laws should be relative to the differences in these passions and to