The Unseen Weight of Being “Normal”

You wake up, a gnawing feeling already settling in your stomach. Another day, another relentless march towards a perfection that feels perpetually out of reach. The news whispers of a collective malaise, a rising tide of anxiety, depression, and burnout. Friends confess their struggles in hushed tones, colleagues seem perpetually on edge. It feels like we’re all caught in an invisible current, swept away by a stress we can’t quite name, a pressure to conform to an unspoken ideal.

But what if this pervasive anxiety isn’t just a modern affliction, a byproduct of digital overload or global uncertainty? What if its roots stretch back further, intertwined with a fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to be “normal,” a misunderstanding quietly shaping our minds since the 19th century?

The Ghost of the Statistical Average

Imagine the intellectual landscape of the 19th century: a world captivated by scientific measurement, by the allure of objective truth. This era gave us the idea that “normal” could be understood statistically. Health became an average, a point on a bell curve. Deviation from this average was, by definition, “pathological.” It was a neat, quantifiable way to categorize the world, a seemingly rational framework for understanding the human condition.

This mechanistic view, initially applied to physical health, gradually seeped into our understanding of the mind. Happiness, productivity, resilience—these too became benchmarks, statistical ideals against which we are constantly measured. The problem? Life, and especially the human mind, resists such neat categorization. This constant pressure to conform to societal ideals of happiness and productivity is a major driver of modern anxiety, often leading individuals to feel pathologized for natural human experiences. We’re told to “be positive,” to “bounce back quickly,” to “optimize” every facet of our existence. Any deviation from this idealized, statistically “normal” state becomes a source of internal conflict, a sign of personal failure.

To declare what is normal implies the power to set the norm, and thus to define what deviates, what is abnormal, what is pathological.

— Georges Canguilhem (paraphrased)

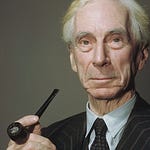

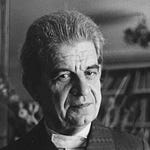

Georges Canguilhem: A Radical Prescription

Enter Georges Canguilhem, a French philosopher and physician whose seminal work, “The Normal and the Pathological,” published in 1943, delivered a profound critique of this very idea. Canguilhem wasn’t just a theorist; he was a man who understood the lived reality of illness and health, challenging the cold, objective gaze of purely scientific medicine. He argued that the statistical definition of normality fundamentally misunderstands what it means to be alive and vital.

For Canguilhem, health isn’t simply the absence of disease or conformity to an average. It’s something far more dynamic, more personal, more *active*.

The Power to Create Our Own Norms

Canguilhem’s genius lies in his redefinition of health not as a static state, but as a capacity. To be healthy, he argued, is not to perfectly align with a statistical average, but to possess the “power to surmount the crisis, to institute new norms” in the face of life’s challenges. It’s the ability to innovate, to adapt, to *create* your own unique way of living and thriving, even when external circumstances change or become adverse.

Consider this: if a fish is removed from water, it is clearly “abnormal” in its new environment. But Canguilhem would ask: does this fish have the capacity to establish new biological norms to survive out of water? No. Its “abnormality” is pathological because it lacks the capacity to adapt, to create a new way of being. In contrast, a human facing a new challenge—say, losing a job or a loved one—may deviate from a prior “normal” state of happiness, but if they have the capacity to grieve, to seek new opportunities, to redefine their purpose, they are exhibiting a form of health, a vitality that transcends mere statistical averages. The relentless pursuit of an externally imposed “normal” often strips us of the very capacity to define and live our own unique, vital existence.

Reclaiming Our Vitality in an Anxious World

How does Canguilhem’s profound insight help us navigate our current anxiety epidemic? It offers a liberation, a radical re-evaluation of what we consider “broken” or “sick” within ourselves. Instead of measuring ourselves against a societal ideal of ceaseless happiness or unwavering resilience, we can begin to trust our own internal compass, our own capacity to create meaning and adapt.

Question the External Norms: Are the “norms” of success, happiness, or mental equilibrium we’re chasing truly our own, or are they impositions from an external world that benefits from our conformity? Watch this thought-provoking video on how external forces shape our minds and perceptions: The Invisible War For Your Mind.

Embrace Your Capacity to Deviate: Perhaps your anxiety isn’t a sign of pathology, but a natural, even necessary, response to a truly abnormal situation. Or perhaps it’s a signal that your old “norms” are no longer serving you, and it’s time to forge new ones.

Focus on Vitality, Not Just Absence of Symptoms: Are you able to fall ill and recover? To feel sorrow and find a new path forward? To adapt creatively to setbacks? This dynamic capacity, not a static state of “perfect” mental health, is the true mark of Canguilhem’s “health.”

To be healthy is to be able to fall ill and recover, it is a kind of biological luxury that an organism can afford.

— Georges Canguilhem

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Breaking Free from the Tyranny of Normality

The anxiety epidemic, then, is not just a personal struggle but a philosophical one. It’s the silent toll of a 19th-century idea that, by reducing us to statistical averages, diminishes our inherent capacity for adaptation, for forging our own unique path through life. By understanding Canguilhem, we can begin to dismantle the invisible prison of “normality” and reclaim our agency. We can learn to listen to our anxieties not as failures, but as signals—signals that we are vital beings, struggling to create new norms in a world that often demands we simply conform. This shift in perspective isn’t just academic; it’s a blueprint for mental liberation, inviting us to live not just “normally,” but fully and authentically.