Imagine a perfect world. A sanctuary where every need is met, where sustenance is infinite, shelter abundant, and predators nonexistent. A utopia, by all definitions. What would happen then? Would life flourish, reaching new heights of complexity and societal achievement? Or would something far more insidious, something fundamentally disturbing, begin to fester beneath the surface of this manufactured paradise?

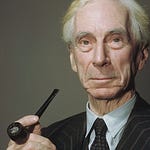

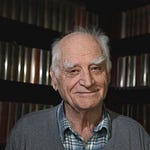

It’s a question that plagued Dr. John B. Calhoun, an ethologist and behavioral researcher, for decades. His relentless pursuit of an answer led him down a path many found unsettling, culminating in a series of experiments so stark in their implications, they continue to echo with a chilling prophecy for humanity.

Calhoun didn’t study humans, not directly. He studied rats and mice. But what he discovered about their social structures, when pushed to the absolute limits of density and resource saturation, revealed a dark potential within any complex social species, ourselves included. His most infamous creation, “Universe 25,” wasn’t just an experiment; it was a blueprint for a self-made apocalypse.

The Architect of Despair: John B. Calhoun’s Vision

Dr. Calhoun began his work in the 1950s, meticulously constructing enclosed environments for rodent colonies. His aim was simple: to observe the effects of population density on behavior. He started small, but his ambition grew, leading to increasingly elaborate setups designed to simulate an ideal existence – a “mouse utopia.”

He wasn’t merely interested in survival rates. Calhoun sought to understand the intricate social fabric of a community. How did hierarchies form? How did mothers raise their young? What happened when the pressures of resource scarcity were entirely removed, replaced by an abundance so complete it bordered on the absurd?

Many different species of animals, including man, are gregarious. Thus, a minimum density of population is necessary for normal social behavior and for healthy social development. Below this minimum, many forms of aberrant behavior are observed. When this minimum density is exceeded, other pathological behaviors appear.

— John B. Calhoun, “Population Density and Social Pathology” (1962)

This quote encapsulates the core of his hypothesis: there’s an optimal zone for social interaction. Too sparse, and communities wither. Too dense, and something far more terrifying emerges.

Universe 25: A Rodent Utopia’s Downfall

“Universe 25” was Calhoun’s magnum opus, launched in 1968. It was a perfectly designed enclosure, built to house thousands of mice. Every possible amenity was provided: an endless supply of food and water through gravity-fed dispensers, nesting materials, and an optimal temperature. Disease was kept at bay, and predators were nonexistent. It was, in essence, a paradise for mice.

The experiment began with just four pairs of mice. They thrived, as expected. With unlimited resources and no threats, their population doubled every 55 days. Life was good, and the colony expanded rapidly, filling the available space. But then, a subtle shift began to occur.

As the population approached 600 individuals, and continued to climb towards its peak of 2,200, the physical space started to feel crowded, even with abundant resources. The mice, inherently social creatures, found themselves in constant proximity. This wasn’t a struggle for food or water; it was a struggle for social space, for individual recognition, for the very meaning of their existence within the horde.

This is where the “behavioral sink” emerged.

Social Breakdown: Traditional hierarchies dissolved. Males struggled to establish territories or defend females. Females, overwhelmed, began to abandon their young, leaving them to die or even cannibalizing them.

The “Beautiful Ones”: A distinct class of males emerged. They withdrew from all social interaction, neither fighting nor mating. They spent their days meticulously grooming themselves, eating, and sleeping, completely disengaged from the chaotic world around them. They were physically perfect, but socially dead.

The “Profoundly Withdrawn”: Females, too, showed signs of extreme pathology. Many ceased reproducing altogether, becoming isolated and aggressive towards any who approached. Others would gather in specific areas, engaging in abnormal social patterns, apathetic to their surroundings.

Homogenization and Deviance: Sexual behavior became distorted. Hypersexuality coexisted with pansexuality, as mice lost the ability to discern appropriate partners or cues. Cannibalism, once unheard of, became common, targeting the weakest and the young.

The Final Collapse: Birth rates plummeted, and infant mortality soared, reaching 100% in some sections. Even when new spaces were opened, the mice seemed incapable of recolonizing them. The collective memory of how to raise young, how to engage in complex social interactions, appeared lost. The population began to decline rapidly, not from disease or starvation, but from a complete breakdown of viable social behavior. Within a mere 600 days from the start of the behavioral sink, “Universe 25” reached its grim conclusion: extinction.

The mice had been given everything, and in turn, they had lost everything.

Echoes in Our Own Halls: Human Parallels?

It’s easy to dismiss “Universe 25” as merely a mouse experiment, irrelevant to our complex human societies. But can we truly ignore the chilling parallels? Calhoun himself, in a later paper, described the “behavioral sink” as a metaphor for the potential psychological collapse of society.

We live in an increasingly urbanized world. Megacities burst at the seams. While we don’t face a lack of calories, many experience a poverty of meaning, a deficit of authentic connection. Do we see our own “beautiful ones” in the rise of extreme individualism, the retreat into digital cocoons, the meticulous curation of self without genuine engagement?

Are the rising rates of anxiety, depression, social alienation, and a general sense of purposelessness within affluent societies merely coincidental? Are we witnessing a human form of the behavioral sink, where an abundance of material resources masks a profound scarcity of social roles and meaningful interaction?

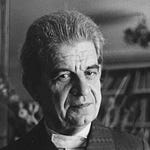

There is no example in history of a civilization in which the decline and fall has not been preceded by the decline in the value and meaning of human life.

— Arnold J. Toynbee

Toynbee’s observation rings with a haunting resonance when viewed through the lens of Calhoun’s mice. The decline wasn’t about the absence of resources, but the absence of purpose, connection, and the fundamental structures that give life meaning.

Avoiding the Sink: Lessons from a Rodent Apocalypse

Calhoun’s experiments offer a stark warning: the mere provision of resources is not enough to sustain a thriving society. Indeed, an overabundance, coupled with unchecked density, can paradoxically lead to a complete collapse of social order and meaning. The lessons from Universe 25 are not about preventing overcrowding in a physical sense, but about understanding the importance of:

Meaningful Roles: Every individual needs a purpose, a contribution, a distinct role within the social fabric. When roles become redundant or impossible to fulfill due to overwhelming numbers, individuals disengage.

Social Cohesion: The ability to form genuine connections, recognize and interact with others in a healthy way, and maintain community bonds is paramount.

Psychological Space: Beyond physical space, there’s a need for “social space”—the ability to feel unique, to have one’s individuality recognized, and to avoid the psychological burden of constant, undifferentiated interaction.

The Quality of Interaction: It’s not just about the number of people, but the nature of their interactions. A breakdown in this quality can be more devastating than any physical scarcity.

The true scarcity in a world of plenty might not be material resources, but the opportunities for meaningful existence that give us reason to thrive.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

John B. Calhoun’s “Universe 25” stands as a chilling, prescient experiment. It suggests that even in a world free from want, the greatest threat to a society might come not from external forces, but from within—from the slow, insidious decay of social bonds, purpose, and meaning when a critical mass is reached. It serves as a powerful, unsettling reminder that our human ingenuity in solving material problems must be matched by an even greater wisdom in fostering vibrant, meaningful, and genuinely connected communities. Otherwise, our utopia may become our undoing.