Have you ever felt caught between two impossible choices? A quiet sense of dread, a knot in your stomach, where no matter what you do, you seem to lose? Perhaps you’ve been told to “be spontaneous!” – a command that instantly negates the very spontaneity it demands. Or maybe you’ve encountered a subtle, yet crushing, contradiction in a relationship, where affection comes with a chilling withdrawal, leaving you questioning your own sanity.

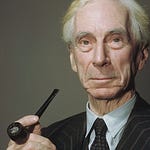

These aren’t just fleeting moments of confusion. For Gregory Bateson, the brilliant polymath who transcended anthropology, biology, and psychology, such paradoxical communication wasn’t merely frustrating; it was the very architecture of mental distress, a blueprint for invisible prisons that could erase the self. Bateson didn’t just study systems; he saw how communication itself could become a cage, twisting reality until the bars were no longer visible, but deeply etched into the mind.

The Invisible Chains of Communication: Understanding the Double Bind

At the heart of Bateson’s groundbreaking work was the concept of the “double bind.” Imagine a situation where you receive two conflicting messages, one negating the other, often on different levels of communication. The spoken words might convey love, but the tone, gesture, or context might communicate rejection. And crucially, there are two more conditions:

No Escape: You cannot leave the situation. It’s often a relationship vital for survival or identity (e.g., parent-child).

No Meta-Communication: You cannot comment on the conflict. You’re forbidden, implicitly or explicitly, from pointing out the contradictory nature of the messages.

Consider a child whose mother says “I love you” while simultaneously stiffening and pushing them away. The child is caught. To respond to the verbal message means ignoring the non-verbal; to respond to the non-verbal means rejecting the verbal. And to say, “Mom, you say you love me, but you’re pushing me away,” might be met with denial or anger, further invalidating the child’s perception.

The schizophrenic is not only unable to make choices, but he is unable to comment on the impossibility of choice.

— Gregory Bateson

This “invisible war” for the mind, as Bateson and his team realized, didn’t just create confusion; it could contribute to severe mental illness, notably schizophrenia, by continually undermining a person’s ability to interpret reality and trust their own experience. This wasn’t about individual pathology in isolation, but about the pathological patterns embedded within relationships and communication systems.

Constructing the Mental Prison

When double binds become a recurring pattern, especially in formative years, they don’t just cause momentary distress; they construct a psychological prison. The mind, constantly barraged by contradictory signals it cannot resolve or escape, adapts by internalizing the paradox. The world becomes a place of no-win scenarios, where safety and self-expression seem mutually exclusive.

This is where Bateson’s broader interdisciplinary approach comes into view. His influence on “systems thinking” extends far beyond individual psychology, showing how these dynamics play out in families, organizations, and even societal structures. The mental prison isn’t just in the individual’s head; it’s a reflection of the systemic dysfunction around them. The person learns to expect contradiction, to doubt their perceptions, and to constantly seek an impossible resolution.

The Erasure of Self: A Quiet Annihilation

The most profound consequence of living within this mental prison is the “erasure of self.” When one’s ability to discern truth from falsehood, affection from rejection, or agency from powerlessness is continually compromised, what remains of the self? The individual’s sense of identity, their authentic feelings, and their internal compass become blurred, then fragmented, and ultimately, can seem to disappear.

Imagine the profound isolation that comes from not being able to trust your own thoughts or emotions, because every attempt to express them is met with invalidation or a contradictory response. The ability to form coherent thoughts, to make choices, or even to know what one truly desires becomes a monumental struggle. It’s a quiet annihilation, a slow fading of the unique individual into a nebulous state of confusion and compliance.

The greatest prison isn’t made of steel, but of invisible, contradictory messages that twist our perception of reality and ourselves.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Pathways to Liberation

While Bateson’s insights paint a stark picture, they also offer the first step towards liberation: awareness. Understanding the dynamics of the double bind and how mental prisons are built is crucial. How do we begin to dismantle these invisible walls?

Meta-Communication: The forbidden act. Learning to talk about the communication itself. “I’m confused because your words say X, but your actions say Y.” This challenges the bind directly.

Boundary Setting: Recognizing and asserting one’s own reality. Even if the other person denies the contradiction, acknowledging it internally is a vital step toward reclaiming self.

Seeking Clarity: Actively asking for clarification when messages are ambiguous or contradictory, rather than internalizing the confusion.

External Validation: Finding others who can validate your perceptions and provide a reality check, breaking the isolation of the mental prison.

The individual is not separable from his environment; he is a part of it.

— Gregory Bateson

Bateson’s work reminds us that our mental landscapes are deeply interwoven with our relational environments. The path to freedom involves not just introspection, but a courageous engagement with the communication systems that shape us. The “additional context” that Bateson’s interdisciplinary approach and influence on systems thinking extends beyond psychology is key here: these principles can be applied to understand and improve communication in families, workplaces, and even political discourse, showing us that these “prisons” are not just psychological but systemic constructs that can be understood and, perhaps, deconstructed.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

Gregory Bateson gifted us a lens through which to see the insidious power of communication. His exploration of the double bind revealed how subtle, contradictory messages can warp our sense of reality, build mental prisons, and ultimately lead to the erasure of self. But in illuminating these dark corners, Bateson also offered a glimmer of hope: the power of conscious awareness and the courage to challenge the paradoxical. In an increasingly complex world, understanding the invisible war for our minds is not just an academic exercise; it’s a vital tool for safeguarding our sanity, preserving our authentic selves, and building healthier, more honest connections.