There’s a chill that settles deep in the bones of existence, isn’t there? A profound loneliness that gnaws at the edges of our being, driving us relentlessly towards others. We crave connection, the warmth of another soul to ward off the existential cold. We reach out, tentatively at first, then with increasing desperation, hoping to find solace, understanding, a refuge from the self.

Yet, how often does that pursuit of closeness end not in comfort, but in a familiar, searing sting? A clash of wills, an unintended wound, a sudden, inexplicable repulsion that forces us to retreat, nursing our hurts? Why does the very act of seeking intimacy so often seem to guarantee pain?

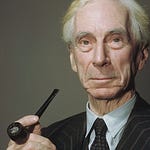

Arthur Schopenhauer, the German philosopher known for his starkly pessimistic worldview, understood this paradox with brutal clarity. He didn’t just observe it; he encapsulated it in a metaphor so piercingly accurate that it has become an enduring symbol of the human condition: “The Hedgehog Dilemma.”

The Frosty Plain of Existence

Imagine, for a moment, the world as Schopenhauer saw it: a desolate, frigid landscape where individual consciousnesses, like isolated hedgehogs, shiver in the cold. Schopenhauer believed that at the core of all being is a blind, irrational, ceaseless striving “Will,” which manifests in us as an endless stream of desires. And desire, by its very nature, is a lack, a suffering.

Our lives, then, are a constant oscillation between the pain of wanting and the fleeting, quickly satiated boredom of getting. Happiness, if it exists, is merely the brief cessation of suffering, a momentary pause before the “Will” asserts its next demand. It’s not a pretty picture, is it? But it’s within this bleak understanding that the “Hedgehog Dilemma” truly comes alive.

The Hedgehog Dilemma: Prickles and Pain

Schopenhauer painted a vivid image:

A company of hedgehogs was driven together by a cold winter’s day. Soon they felt the need for warmth from each other; but when they came too close, they felt each other’s prickles. So they moved apart again. Now the need for warmth brought them together once more, but then the prickles reappeared. This went on for some time, so that they were driven back and forth between two evils, until they found a moderate distance from which they could best tolerate each other.

— Arthur Schopenhauer

This isn’t just a charming fable; it’s a profound philosophical paradox. We humans, much like those hedgehogs, are driven by an inherent need for warmth – for connection, love, belonging. But as we draw closer, our individual “prickles” inevitably emerge. These aren’t necessarily malicious intent, but rather the sharp edges of our personalities, our unspoken needs, our incompatible desires, our deeply ingrained flaws, and our often-unreasonable expectations.

The closer we get, the more acute these collisions become. What we desire in intimacy – true understanding, unwavering support, complete acceptance – often conflicts with the reality of two distinct individuals, each carrying their own baggage, their own hurts, their own selfish “Will.” This is the bitter truth: the closer we get to others, the more we inevitably hurt each other, forcing us into a painful dance of approach and retreat, leading us back towards a lonely isolation.

The Dance of Proximity

So, what’s the solution? Schopenhauer, ever the realist, didn’t offer a magic cure. Instead, he suggested that the hedgehogs eventually found a “moderate distance” from which they could best tolerate each other. This “moderate distance” is the core of his insight into human relationships.

It’s the unspoken agreement to maintain certain boundaries, to hold back parts of ourselves, to acknowledge that absolute fusion with another is not only impossible but actively damaging. It’s why:

Friendships have limits: We share laughs, support, and companionship, but rarely the raw, unfiltered torment of our deepest selves.

Romantic relationships struggle: The initial intoxicating closeness often gives way to friction as two independent “Wills” collide, leading to arguments, resentment, and a desire for personal space.

Family ties are complex: The very people we are closest to can also be the source of our deepest wounds, simply because the shared history and proximity offer so many opportunities for “prickle” encounters.

The pain isn’t a sign of a failed relationship, but often an unavoidable consequence of its very existence. It’s the friction generated by two distinct beings attempting to share space, to merge, to truly know one another.

Beyond the Prickles: Acceptance and Awareness

Schopenhauer’s dilemma isn’t an instruction to avoid intimacy altogether, but rather a somber observation on its inherent nature. If human intimacy always ends in pain, does that mean we should simply accept loneliness?

Not necessarily. His philosophy encourages a kind of intellectual resignation, an awareness that the discomfort and occasional wounds are not anomalies, but rather part and parcel of the human experience. Understanding this can, ironically, make the pain less personal, less devastating. It helps us manage our expectations, to approach relationships with a clearer, albeit more sober, perspective.

The inherent tragedy of human connection lies in our inescapable need for proximity clashing with the unavoidable reality of our individual, wounding edges.

Perhaps, then, the wisdom isn’t in finding a way to eliminate the prickles, but in learning to appreciate the warmth that can still be found at a “moderate distance,” and in accepting the occasional sting as an inevitable cost of seeking companionship in a cold world. It’s about finding a balance, not a perfect solution. A balance between the warmth we crave and the inevitable pain we inflict, and receive, along the way.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

A Sobering Reflection

Schopenhauer’s “Hedgehog Dilemma” forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth about ourselves and our relationships. It’s a reminder that genuine intimacy is not a frictionless ideal, but a continuous, often challenging negotiation between connection and self-preservation. While his view might seem bleak, it offers a stark realism that can be strangely liberating. By understanding the inherent difficulties, we can approach our bonds with others not with naive optimism, but with a profound, compassionate awareness of the “prickles” we all carry, and the brave, often painful, dance we perform to keep the cold at bay.