Two thousand years ago, an Athenian historian named Thucydides watched his world tear itself apart. He meticulously chronicled the Peloponnesian War, not merely as a sequence of battles, but as a tragic drama driven by forces far older and deeper than human will. His diagnosis? A timeless disease of power, a structural flaw in the very fabric of international relations. “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

This chilling observation birthed what we now call the “Thucydides Trap”: the perilous dynamic where a rising power threatens an established one, often leading to conflict as the default outcome. Is this ancient logic, forged in the crucible of classical Greece, still pulling the strings of our modern world? Are we, despite our technological marvels and diplomatic aspirations, merely re-enacting a script written millennia ago?

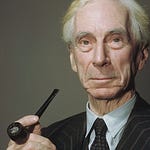

This question leads us directly to the cold, terrifying, and seemingly unavoidable reasons why great powers are so often destined to clash. We journey not into the realm of good versus evil, but into the iron cage of international politics, guided by the brutal theory of political scientist John J. Mearsheimer . His concept of Offensive Realism offers a stark, unblinking look at a world with no global 911, where survival itself dictates a relentless pursuit of power.

This is a tragedy of rational actors, caught in a system that punishes trust and rewards suspicion, forcing them toward a foregone conclusion. The analysis of Thucydides and John J. Mearsheimer has never been more relevant. If you want to understand the grim calculus that governs our world, this is a conversation we cannot afford to ignore.

The Ancient Echo: Thucydides’ Enduring Insight

Thucydides, through his monumental work “History of the Peloponnesian War”, offered humanity a mirror, reflecting not just the events of his time, but the timeless drivers of human conflict. He saw beyond the immediate provocations, identifying a deeper, more structural reality. The Peloponnesian War, to him, was not an accident but an inevitability, born from the fear and insecurity inherent in a world of competing powers.

He articulated the core motivations that drive states: fear, honor, and interest. Fear of being dominated or destroyed; honor, seeking respect and standing; and interest, the pursuit of security and prosperity. These are not merely abstract concepts; they are deeply ingrained human impulses projected onto the grand stage of international relations.

The “Thucydides Trap” describes this structural flaw: when a new power rises, its very growth generates anxiety in the established hegemon. This anxiety, often manifesting as fear, can trigger a cycle of suspicion and counter-measures, making war not just possible, but tragically probable.

It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.

— Thucydides

This isn’t a moral judgment; it’s a diagnosis of a systemic condition. Thucydides laid bare the logic of great power competition, a logic that, horrifyingly, seems to repeat itself across millennia.

The Iron Cage: Mearsheimer’s Brutal Realism

Fast forward to the modern era, and we find a direct intellectual heir to Thucydides in John Mearsheimer. A leading proponent of “Offensive Realism,” Mearsheimer picks up where the Athenian left off, but with a sharper, more unforgiving edge. His theory posits that the international system is anarchic, meaning there is no overarching authority to enforce rules or protect states.

Think of it as a world with no global 911. When trouble strikes, each nation is ultimately on its own. In such a dangerous environment, Mearsheimer argues, the only rational path to survival is the relentless pursuit of power. States cannot afford to be complacent; they must constantly seek to maximize their relative power, even at the expense of others, because intentions can never be truly known, and the capacity to harm always exists.

This isn’t about aggression for aggression’s sake, but a structural imperative. States act defensively by trying to become as powerful as possible. This creates a perpetual security dilemma: what one state does to enhance its own security is inevitably perceived as a threat by another, leading to a dangerous spiral.

States operate in a self-help world. Each state must provide for its own security, and because no state can ever be certain of another state’s intentions, it must always assume the worst.

— John J. Mearsheimer

Mearsheimer’s analysis is cold, but it claims to be accurate. He sees the dilemma as permanent, a tragic reality where rational actors, seeking only to secure their survival, are locked into a competition that often leads to conflict. There’s no escaping the “iron cage” of international politics.

Technology’s Double-Edged Sword: Reinforcing the Trap

One might hope that modern advancements could somehow transcend this ancient, brutal logic. Hasn’t globalization, interdependence, and shared challenges like climate change created a new paradigm? Unfortunately, from the Mearsheimerian perspective, the answer is a resounding ‘no’.

Modern technology, far from breaking the trap, has often reinforced its walls and accelerated the timeline to catastrophe. Consider:

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The race for AI dominance isn’t just economic; it’s military. The nation that masters autonomous weapon systems or advanced cyber capabilities gains a significant, potentially decisive, strategic advantage, fueling greater fear in competitors.

Cyber Warfare: The ability to cripple an adversary’s infrastructure without firing a shot introduces new vulnerabilities and opportunities for covert aggression, blurring the lines of conflict and intensifying distrust.

Weaponized Economic Interdependence: What was once seen as a guarantor of peace can now be weaponized. Sanctions, trade wars, and control over critical supply chains become instruments of power projection, deepening rivalries rather than fostering cooperation.

Each technological leap, while promising progress, simultaneously offers new avenues for gaining power and new reasons to fear one another. The fundamental structural dilemma remains, only now armed with more sophisticated tools and operating at a faster pace.

The Grim Calculus and the Human Element

The combined insights of Thucydides and Mearsheimer paint a grim picture. It suggests that major wars between great powers are not aberrations, but rather the tragic, logical outcome of a system devoid of ultimate authority. It’s a calculus where states, driven by existential fear, prioritize security above all else, often making decisions that, while rational from their own perspective, lead collectively to disaster.

This isn’t a story of irrational leaders or misguided policies alone. It’s a tragedy of perfectly rational actors caught in an unforgiving environment. Trust is a liability, transparency is a risk, and suspicion is often rewarded. The system itself seems rigged against peace, pushing nations towards a relentless, often violent, competition for survival.

Understanding this brutal logic is not an endorsement of it, but a necessary step towards navigating a world where the stakes are incredibly high. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about human nature and the anarchic nature of international politics.

Is There an Off-Ramp? A Call to Reflection

Given this seemingly inevitable logic, is there any hope? Can human foresight, wisdom, or sheer will defy this structural imperative? Can we construct an off-ramp from the “Thucydides Trap,” or is the cycle truly unbreakable?

Some argue for diplomacy, international institutions, and shared values as potential counter-forces. Others point to the catastrophic costs of modern warfare as a deterrent. Yet, the realist perspective reminds us that these factors operate within the constraints of an anarchic system, often bending to the underlying forces of fear and power.

Perhaps the off-ramp isn’t about fundamentally changing the system, but about understanding its constraints and playing within them more skillfully. It demands a clear-eyed assessment of threats, a pragmatic approach to alliances, and a constant vigilance against complacency. It means recognizing that peace is not merely the absence of war, but a precarious balance maintained through continuous effort and a deep understanding of the forces at play.

The conversation doesn’t end with the diagnosis of the trap; it begins there. How do we, as a global society, navigate these treacherous waters? What policies can mitigate the worst impulses of great power competition without succumbing to naive optimism?

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

The insights of Thucydides, echoed and amplified by John Mearsheimer, serve as a stark reminder of the enduring nature of power politics. From the ancient Greek city-states to the nuclear-armed giants of today, the fundamental drivers of fear, honor, and interest continue to shape the destiny of nations. The “Thucydides Trap” isn’t a historical anomaly; it’s a recurring pattern, a structural challenge that defines the very architecture of our world.

This isn’t a comforting narrative. It’s a call to intellectual rigor, to abandon wishful thinking in favor of a clear-eyed understanding of the world’s most dangerous dynamics. Only by grappling with the “inevitable logic of war,” by dissecting the mechanics of fear and the pursuit of power, can we even begin to chart a course away from catastrophe. The conversation about Thucydides and Mearsheimer is not just academic; it is vital. It is about the future, and it concerns us all.