Imagine you’re sitting in a quiet café, lost in a book. The world outside your table has dissolved. The clatter of cups, the murmur of conversation, the hiss of the espresso machine—it’s all just distant texture. In this private bubble, you are pure consciousness, a flow of thought and imagination. You are, in a word, free.

Then, you feel a subtle shift in the atmosphere. A stillness. You look up and catch the eye of someone across the room. They aren’t staring aggressively, maybe just a fleeting, idle glance. Yet, in that single instant, everything changes. The book in your hands feels like a prop. The way you’re sitting suddenly seems awkward, rehearsed. You are no longer a person reading; you are an object being perceived, a character in someone else’s story titled “That person reading a book.”

Your universe, once centered on you, has been hijacked. It now revolves around the person watching.

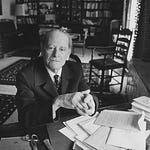

This silent, destabilizing transaction was the obsession of French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. He gave it a name: “The Look” or “The Gaze.” For Sartre, this wasn’t just a moment of social anxiety. It was the fundamental, and most terrifying, mechanism of human interaction. It is the invisible force that underpins his most famous and chilling declaration: “Hell is other people.”

The Invisible Courtroom

What makes another person’s gaze so powerful? According to Sartre, we exist in two radically different ways.

In our own minds, we are a “Subject.” We are a limitless current of intentions, possibilities, memories, and dreams. We are not a fixed thing; we are a constant process of becoming. When you are alone, you experience this freedom most purely. You are the author, director, and star of your own reality.

The moment another person looks at you, however, you are ripped from that role. Under their Gaze, you are instantly transformed into an “Object.” You become a thing in their world, defined by external properties they assign to you: “tall,” “serious,” “well-dressed,” “nervous.” Your infinite inner world collapses into a finite, external label. And the most terrifying part? You have no control over what that label is.

Their perception becomes a prison. Their judgment, even if unspoken or indifferent, builds the walls. Every encounter, then, is a silent battle for subjectivity. Who gets to be the free consciousness, and who is forced to become the defined object?

The Anatomy of a Fall

To grasp the true violence of The Gaze, Sartre asks us to imagine a man driven by jealousy to peek through a keyhole. Alone in the hotel corridor, he is pure, unthinking intention. He isn’t judging himself; he is simply a vector of curiosity, a consciousness directed at the scene in the room. In his own mind, he is a ghost absorbing the world. He is a Subject, utterly free.

Then, he hears a floorboard creak behind him.

In that stomach-dropping instant, the universe reorients. He has been seen. The person who saw him now holds all the power. They are the Subject, and he, caught in the beam of their perception, has become an Object. He is no longer an invisible flow of jealousy; he is pinned down like a butterfly in a display case. He is “a man peeping through a keyhole.” A voyeur. A sneak.

The overwhelming emotion that accompanies this transformation is shame. It’s not just embarrassment. It’s a profound, existential shame—the shame of having your very being stolen from you and replaced with a crude caricature. You are no longer living your experience from the inside out; you are forced to see yourself from the outside in, through the alien consciousness of your observer.

Shame... is the recognition of the fact that I am indeed that object which the Other is looking at and judging.

— Jean-Paul Sartre

This is what Sartre calls “the fall.” It’s the fall from the grace of subjective freedom into the hell of objective definition. Your possibilities freeze. Before the footstep, you could have done anything. After, you are trapped in that single, captured action, defined by it for an eternity in the mind of the other.

A Global Hall of Mirrors

Sartre’s terrifying transaction is no longer confined to a chance encounter in a hallway. We have taken this episodic nightmare and engineered it into the permanent architecture of modern life. The digital world is a global stage where the audience is everyone and the performance never ends.

The Gaze is no longer just the person standing behind you; it is the latent, potential Gaze of billions, filtered through the cold lens of a smartphone. We now live our lives in constant anticipation of The Look. We don’t wait for the floorboard to creak; we broadcast our location, inviting the world to turn us into an object.

Every social media post is an act of willing self-objectification. We aren’t sharing our subjective experience; we are crafting an object—”the happy traveler,” “the successful professional,” “the loving parent”—and offering it up for judgment. We are performing our own freedom, which is the most profound form of unfreedom imaginable. The anxiety of waiting for likes is the digital echo of Sartre’s shame, a confirmation that our object-self has been seen and evaluated.

This extends far beyond our screens. The open-plan office, with its culture of constant visibility and performance metrics, is an arena of mutual observation. We are not people doing a job; we are resources being optimized. We have internalized the observer so completely that we have become our own wardens, adjusting our behavior for a hypothetical Gaze even when we are alone.

The Freedom to Gaze Back

If we are living in a permanent state of being watched, is there any escape? For Sartre, the answer isn’t to find a place where no one can see you. That is impossible. The escape is to fundamentally change your relationship with The Gaze itself.

The resistance is a two-fold practice:

Gaze Back. This is not about aggression; it is about restoring equilibrium. When the man at the keyhole hears the footstep, instead of freezing in shame, he could stand, turn, and meet the eyes of his observer. In that moment, he forces the other person to become aware of their own body, their own object-hood in his eyes. He reminds them that he is also a Subject. In daily life, this means refusing to be a passive recipient of judgment. It means acting as a center of consciousness, not just a character in someone else’s play.

Live Authentically. The Gaze gains its power by freezing a spontaneous action into a permanent definition. The antidote is to choose your actions so deliberately that the external label cannot touch your internal intention. An authentic life is one lived from a self-chosen set of values, regardless of the audience. The actions flow from personal conviction, not public performance. When The Gaze falls on an authentic person, any label it creates is irrelevant, because the label was never the point. The act itself was the point.

This is a constant, moment-to-moment discipline. It is the practice of noticing the invisible pressure of the audience, acknowledging its power, and choosing to move anyway. It is accepting the vulnerability of being seen as the very proof of your freedom.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion: Beyond the Prison Walls

We began with a simple feeling—the subtle shift when a stranger’s gaze lands on you in a café. We’ve traced that feeling to the core of Sartre’s philosophy, seeing how it can turn us from free subjects into frozen objects, and how our modern world has amplified this process into a constant, humming pressure.

In the end, Sartre’s infamous line from his play “No Exit” is not a cynical complaint about annoying people. It is a precise diagnosis of the human condition.

So this is hell. I’d never have believed it. You remember all the stories you’ve heard... about the fire and brimstone, the torture-chambers... Ah, what a joke. There’s no need for red-hot pokers. Hell is—other people!

— Jean-Paul Sartre, “No Exit”

The hell is not their flaws. The hell is their consciousness—its inescapable power to define you, to pin you down, and to create a version of you that lives in their mind, completely outside of your control. Perhaps the deepest circle of this hell is realizing how often we willingly seek out this objectification, begging for our identity to be validated by likes, promotions, and nods of approval.

But to recognize the prison is the first step to finding the key. The struggle against The Gaze is the struggle for an authentic life. It is the refusal to become a finished product. True connection is not found in seeking approval, but in those rare moments of mutual recognition, when two free subjects can stand in each other’s presence without the need to conquer or define.

The choice, then, isn’t whether you will be seen. You will be. The choice is what you do in that moment. Do you freeze, accepting the object they have made of you? Or do you stand, meet their eyes, and assert your own story? The world will always try to tell you who you are. Your freedom lies in the quiet, resolute power of knowing they are wrong.