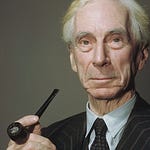

Imagine a world where political corruption isn’t just a moral failing—a few “bad apples” at the top. Imagine if the very structure of our collective endeavors, no matter how noble their initial intent, inevitably channeled power into the hands of a select few. We often tell ourselves a comforting story: replace the greedy with the good, and the system will heal. But in 1911, a German sociologist named Robert Michels delivered a chilling counter-narrative, dismantling that hope with a terrifyingly precise observation.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Michels didn’t just suggest that power concentrates because people are inherently evil; he argued it happens because efficiency demands it. He called this the “Iron Law of Oligarchy.” It’s a concept that forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: even the most democratic grassroots movements, born from pure intentions and collective will, are destined to transform into rule by a small elite. But how does this happen? Is it a theft of power, or something far more subtle and insidious?

The Inevitable Ascent of the Few

Let’s consider Arthur. Arthur was passionate, articulate, and deeply concerned about the quality of his town’s drinking water. He started the “Clean Water Coalition,” a local grassroots movement fueled by frustration and a shared desire for change. Initially, every decision was made democratically, every voice heard. Meetings were long, passionate, and inclusive. But as the Coalition grew, so did its complexity.

Suddenly, there were thousands of members, multiple sub-committees, and a pressing need for funds, legal advice, and public relations. Direct democracy, where everyone votes on every issue, became physically impossible. Who would organize the rallies? Who would draft the petitions? Who would negotiate with the city council? The “sheer weight of logistics” began to crush the original egalitarian vision.

This is where the insidious nature of Michels’ Iron Law reveals itself. As the group expanded, the need for technical expertise became paramount. Someone had to understand municipal zoning laws, water purification processes, and media relations. A division of labor emerged, separating the “directing few” from the “directed many.” These few weren’t villains; they were simply the most informed, the most articulate, or the most dedicated. They became the functional aristocracy, not through a coup, but through necessity.

The Consensual Surrender: “Gratitude of the Masses”

But why do the many allow this? Michels argued it wasn’t a forced takeover but often a “consensual surrender.” He spoke of the “gratitude of the masses”—our psychological desire to let others handle the exhausting burden of self-governance. Running an organization, understanding complex issues, and constantly engaging in debate is draining. Most people, while wanting change, are happy to delegate the heavy lifting.

We often mistakenly believe power is stolen, when in reality, it is frequently surrendered by a populace eager to delegate the exhausting burden of self-governance.

The very act of forming an organization, even one dedicated to democratic ideals, plants the seeds of its own oligarchical fate. The masses, overwhelmed by complexity, naturally defer to those with expertise and energy. This isn’t just about apathy; it’s about the pragmatic reality of managing a large group towards a common goal.

It is a fact of experience that the activity of the individual is always most effective when it is concentrated upon a single object. If, then, the individual must play his part in the collective life of the organized whole, if he is to avoid the danger of losing his individuality in the crowd, it is essential that he should specialize, and that he should choose some definite sphere of action.

— Robert Michels

The Peril of Goal Displacement

As the Clean Water Coalition grew, something else began to shift. The original mission—clean water—slowly started to blur. The focus drifted from fighting for the cause to fighting for the organization’s survival. This is what Michels called “goal displacement.” The leaders, now entrenched, with an organization to run, staff to pay, and a reputation to maintain, began prioritizing the institution itself over its founding ideals.

Decisions were made not necessarily to achieve clean water, but to ensure the Coalition’s continued existence, its funding, its public image. The organizational apparatus, once a tool, started to become the master. Dissenters were marginalized as threats to unity. New ideas were met with resistance if they challenged established procedures or the authority of the leadership. The bureaucracy, once a means to an end, became an end in itself.

The “Circulation of Elites”: A Flawed Antidote?

Is there any escape from this bureaucratic cage? Michels wasn’t entirely pessimistic, but his proposed solution offered only a temporary reprieve. He suggested the “circulation of elites” as the only antidote to this structural trap. This idea posits that new leaders, or new elites, might emerge to challenge the old, thereby preventing absolute stagnation and corruption. However, even these new elites, once in power, would eventually succumb to the same organizational pressures, perpetuating the cycle.

It’s not about replacing one set of bad leaders with good ones, but understanding that the very act of leading, within any complex organization, creates an oligarchical tendency. The system itself, driven by the need for efficiency and stability, molds its leaders into an elite, regardless of their initial intentions.

The politically uneducated masses are always ready to hail a leader, provided he has the qualities of command.

— Robert Michels

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

The Unyielding Mechanics of Power

Robert Michels’ “Iron Law of Oligarchy” is a sobering reflection on the mechanics of power. It challenges our romantic notions of democracy and forces us to consider that the concentration of power isn’t merely a moral failing of individuals, but a structural inevitability driven by efficiency and the psychological comfort of delegation. The organization, designed as a tool, constantly tries to become a master.

So, is true democracy a futile endeavor? Michels would suggest that absolute, direct democracy is indeed “mathematically impossible” in any large, complex society. The sheer scale and demands of governance necessitate a representative structure, which inherently leads to the rule of the few. Our challenge, then, is not to eliminate oligarchy, which is likely impossible, but to constantly resist its corrosive effects, to question the authority of the few, and to engineer mechanisms that encourage continuous accountability and the genuine “circulation of elites.” Only by understanding these unyielding forces can we hope to resist the slide into servitude and keep the flame of democratic ideals burning, however dimly, within the bureaucratic cage.