Roland Barthes: Advertising, Consumerism, & The Hidden Language That Controls You

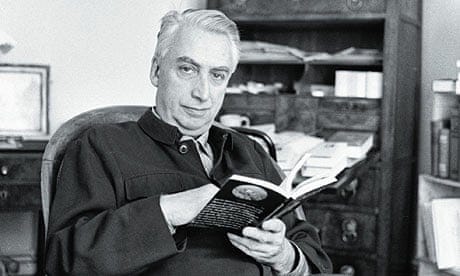

Every day, we are bombarded. From the moment we open our social media feeds to the last flick of the late-night infomercial, messages whisper, suggest, and shout. They tell us what to desire, what to fear, who to be. But what if these messages aren’t just selling products, but entire ideologies? What if the glossy image of a sports car or the smiling family in a cereal ad isn’t merely about buying, but about belief? Roland Barthes, the enigmatic French literary theorist, offered us the tools to peel back these layers, revealing an “invisible war for your mind” waged not with bombs, but with signs and symbols.

Imagine living in a world where everything you see, touch, and consume carries a secret code. A code designed to shape your perceptions, your values, your very understanding of reality. Barthes didn’t just imagine it; he meticulously dissected it. He showed us how advertising and consumerism aren’t just economic activities, but powerful systems of meaning-making, silently orchestrating our desires and directing our lives.

The Mythology of Everyday Life

Barthes’ most famous work, “Mythologies,” published in 1957, was a groundbreaking exploration of how everyday phenomena – from wrestling matches to detergents, from plastic to steak frites – are transformed into “myths.” For Barthes, a myth isn’t a false story; it’s a type of speech, a way of naturalizing a particular ideology. Think of it: an advertisement doesn’t just show a product; it wraps it in layers of cultural meaning, making a specific lifestyle, a certain value system, appear utterly natural and self-evident.

Consider the image of a gleaming SUV conquering rugged terrain. Is it merely selling a vehicle? Or is it selling freedom, adventure, masculinity, and success? Barthes argued that advertising excels at this process, taking a simple object (the car) and imbuing it with a second-order meaning (myth: the adventurous, successful life) that transcends its primary function. These myths are not neutral; they serve to reinforce dominant cultural narratives and power structures.

Myth is depoliticized speech.

— Roland Barthes

This “depoliticized speech” makes the ideological seem innocent, turning specific cultural constructs into universal truths. We accept them without question, precisely because they appear so obvious, so ‘natural.’

Decoding the Advertising Image

To understand how these myths are constructed, Barthes introduced us to the field of semiotics – the study of signs and symbols and their interpretation. Every advertisement is a complex arrangement of signs, each with a “signifier” (the image, the word) and a “signified” (the concept it evokes). When we see a perfume bottle (signifier), it doesn’t just denote a liquid in glass; it connotes elegance, seduction, luxury (signifieds).

Barthes meticulously broke down the layers of meaning within an image:

Denotation: The literal, objective meaning. What is physically present.

Connotation: The subjective, cultural, and associative meanings. What ideas and feelings the image evokes.

Anchorage: How text “anchors” the meaning of an image, directing our interpretation and often limiting the polysemy (multiple meanings) of the visual.

Advertising skillfully manipulates these layers. A picture of a healthy, glowing family eating a specific brand of yogurt is not just denoting yogurt and people; it’s connoting happiness, well-being, responsible parenting. The text often clinches this interpretation, ensuring we don’t miss the intended message. To delve deeper into how these visual tricks work, you might find this video insightful:

Consumerism as a Language

Beyond individual ads, Barthes’ insights extend to consumerism itself as a vast, interconnected system of signs. Our choices in products, brands, and lifestyles are not just practical decisions; they are acts of communication. What kind of car we drive, what clothes we wear, what coffee we drink – these become symbols, speaking volumes about our identity, our social status, our aspirations, and our values.

Advertising doesn’t just sell us products; it sells us the “idea” of ourselves. It taps into our desire to belong, to stand out, to be perceived in a certain way. We buy not just a watch, but the sophistication it represents. We purchase not just a phone, but the connectivity and status it implies. In this intricate dance, consumption becomes a language we speak, often unknowingly, to the world around us.

The world is not a collection of objects, but a collection of signs.

— Roland Barthes

This perspective transforms shopping from a mundane task into a profound, if unconscious, semiotic performance. Every purchase is a statement, every brand a word in our personal narrative.

The Ideological Undercurrents

The true power of Barthes’ analysis lies in its revelation of the ideological undercurrents flowing beneath the surface of advertising and consumer culture. These “myths” are rarely neutral. They reinforce societal norms, perpetuate class distinctions, define gender roles, and often present consumption as the primary path to happiness, freedom, and self-actualization.

Consider how ads often depict traditional family structures or ideal body types, subtly suggesting what is “normal” or “desirable.” They don’t just sell a lifestyle; they sell an ideology of how life “should” be lived. Barthes’ work highlights how advertising often exploits our deepest psychological needs and anxieties, offering consumer goods as false solutions to complex human problems, thereby perpetuating a cycle of superficial satisfaction and continuous desire. This continuous desire, fueled by manufactured images of perfection and fulfillment, keeps the engine of consumerism churning, often at the expense of genuine well-being and critical thought.

The message is clear: if you buy this, you will be happy, loved, successful. If you don’t, you risk being left behind. This isn’t just marketing; it’s a subtle form of social engineering, naturalizing specific worldviews and making them seem like the only sensible options.

The subtle language of advertising shapes our desires, defines our identities, and ultimately dictates our societal values without us ever consciously realizing it.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Beyond the Glamour: Reclaiming Our Minds

Roland Barthes provided us with a powerful lens through which to view the modern world. He didn’t just critique advertising; he gave us the tools to understand its mechanisms, to dissect its hidden messages, and to recognize its ideological ambitions. His work is a call to intellectual arms, urging us to become active decoders rather than passive recipients of cultural narratives.

In a world saturated with commercial messages, understanding Barthes is not just an academic exercise; it’s a vital act of self-preservation. By recognizing the myths woven into our everyday objects and experiences, by distinguishing between denotation and connotation, we begin to reclaim agency over our desires and our understanding of what truly constitutes a good life. It’s an invitation to question the “naturalness” of what is presented to us, to challenge the silent commands, and to finally read between the lines of the invisible script that seeks to control us.

Loved this! These ideas are like an extension of the concepts of the extended alienation and the false necessities that Marcuse talks about!

Blessings and appreciation from Sydney Australia.