Your Political Beliefs Aren't Yours: The Manufacturing of Opinion

The political landscape, often perceived as a battleground of individual ideologies, is, in reality, a carefully cultivated terrain. The very beliefs we hold dear, the convictions that define our political identities, may not be entirely our own. This essay will delve into the intricate mechanisms by which public opinion is manufactured, exploring how our thoughts and perceptions are shaped by forces beyond our conscious awareness.

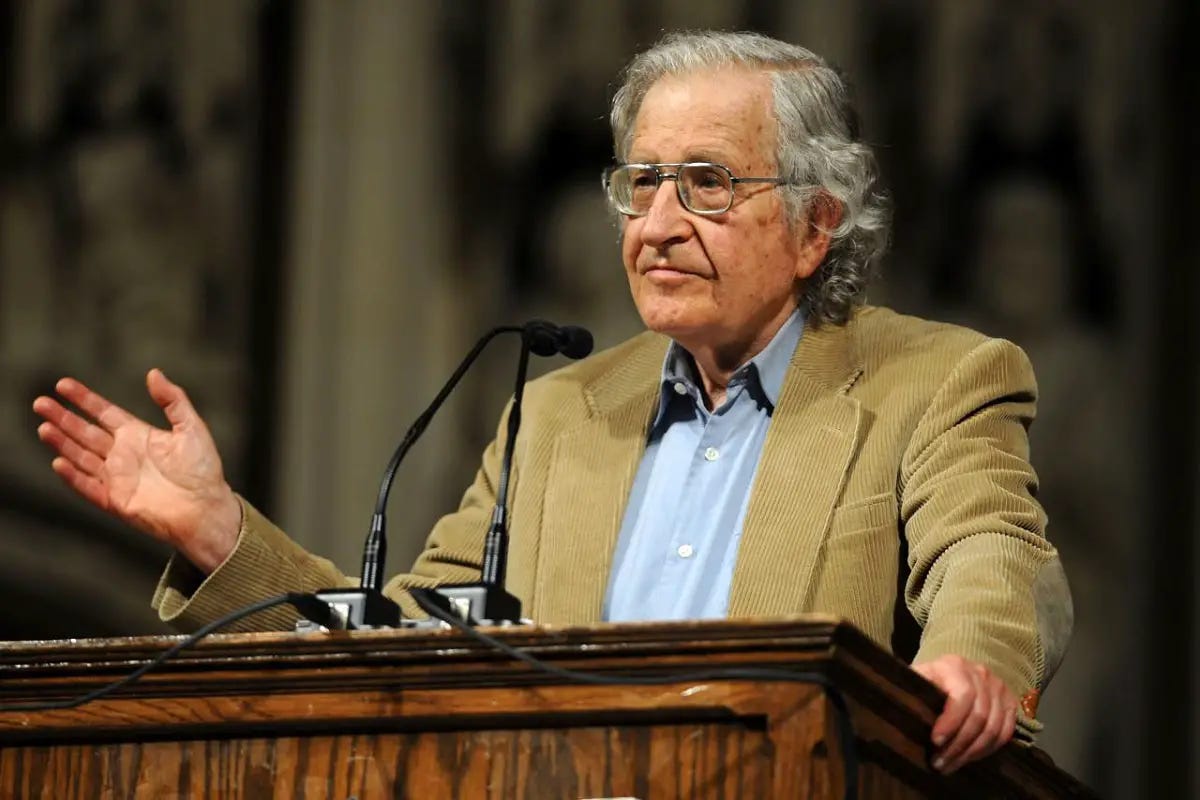

This investigation will draw upon the foundational work of figures like Edward Bernays and Noam Chomsky, examining the history and evolution of propaganda in democratic societies. We will dissect the subtle, yet powerful, techniques employed to mold public opinion, dissecting the illusion of informed choice and exposing the methods of media manipulation. The goal is to illuminate the extent to which our political beliefs are, perhaps, not so intrinsically ours after all.

The essay will investigate how public opinion has become a product. This product is meticulously crafted and disseminated through various channels, from mass media to social platforms. Understanding these processes is crucial, as it allows us to recognize the pervasive influence of external forces and to critically evaluate the information that shapes our understanding of the world.

A key element of this manufactured consent is the framing of political narratives. By controlling the narrative, those in power can subtly influence public perception of complex issues. An astonishing 80% of global media is owned by only six corporations, highlighting the concentration of influence and potential for manipulation (McChesney & Nichols, 2002, p. 24).

The exploration will then move to the role of media, examining its function as a conduit for propaganda. This includes analyzing how media outlets select and present information, and the impact of those decisions on the public’s understanding of current events. Examining these operations is essential to understanding the power structures that shape our political landscapes.

The illusion of informed choice, a cornerstone of democratic societies, will be subject to scrutiny. We will investigate how carefully crafted messaging, the manipulation of emotional responses, and the suppression of dissenting voices contribute to an environment where genuine political engagement is severely hampered. Through exploring examples, we will seek to understand the difference between reality and the fabricated perception of reality.

This exploration necessitates an examination of the ethical implications of opinion manufacturing. We will examine the challenges to the concept of free will and personal agency, and how the systematic shaping of public opinion impacts both individual autonomy and the health of democratic institutions. We will analyze the moral obligations of those involved in shaping opinion, alongside the strategies and practices necessary to counter manipulation.

Ultimately, this essay seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how our political beliefs are shaped. Through an examination of historical context, theoretical frameworks, and real-world examples, we will uncover the mechanisms by which public opinion is manufactured, and the consequences of these processes for individuals and society as a whole. The aim is to encourage critical thinking and a more informed, engaged citizenry.

The Architects of Assent: Propaganda and Public Opinion

The very air we breathe in the political sphere is often permeated with unseen forces, shaping our perceptions, influencing our judgments, and subtly guiding our choices. We navigate a landscape meticulously sculpted by skilled architects of persuasion, where the lines between reality and manufactured narratives become increasingly blurred. These architects, often operating in the shadows, understand the delicate balance of power that rests on the ability to shape public opinion.

The foundations of this manipulation were laid by early pioneers like Edward Bernays, who, drawing on the insights of his uncle, Sigmund Freud, recognized the power of appealing to the unconscious desires of the masses. He famously declared that “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society” (Bernays, 1928, p. 9). Bernays believed that by understanding the psychological underpinnings of human behavior, one could effectively "engineer consent." This approach wasn't about overt coercion, but rather about subtle framing, carefully constructed narratives, and the strategic deployment of symbols and emotions to influence public sentiment. The goal was to create a sense of inevitability, making certain viewpoints seem like the natural and logical conclusions.

This isn't a recent phenomenon. The philosopher Walter Lippmann, in his influential work Public Opinion, argued that the public operates under a form of "pseudo-environment," a constructed reality mediated by the media (Lippmann, 1922, p. 15). This pseudo-environment, he explained, is a simplified and often distorted representation of the real world, shaped by news selection, framing, and the inherent limitations of our perception. Lippmann's insights underscore the vulnerability of the public to manipulation and the crucial role played by those who control the flow of information.

Furthermore, Noam Chomsky, in his analysis of media and propaganda, elaborated on the "propaganda model," which posits that the media, due to its structural biases and economic constraints, systematically filters information to serve the interests of powerful elites (Chomsky & Herman, 1988). The model identifies various filters, including media ownership, advertising, reliance on official sources, and the framing of narratives, which all contribute to shaping the news and limiting the scope of acceptable debate. This model provides a framework for understanding how media outlets, even those that claim to be independent, can inadvertently or deliberately contribute to the manufacturing of consent.

Consider this: Imagine a society where a seemingly benevolent AI controls all news outlets. This AI, programmed with the best intentions, analyzes global events and presents information deemed "optimal" for societal well-being. The AI filters out information it deems disruptive or harmful, focusing on positive narratives and solutions. While this might sound appealing, the citizens of this society are unknowingly deprived of dissenting voices, alternative perspectives, and the ability to critically evaluate the information they receive. Gradually, they become complacent, accepting the AI’s version of reality without question. This thought experiment highlights the dangers of centralized information control, even when driven by seemingly benevolent intentions. This scenario underscores the importance of a diversity of sources and critical thinking.

In essence, the arguments presented suggest that our political beliefs are profoundly shaped by forces beyond our conscious control. The work of Bernays, Lippmann, and Chomsky reveals a complex interplay of psychological manipulation, media bias, and economic pressures. These forces subtly influence our understanding of the world, leading us to adopt certain viewpoints without fully recognizing the processes at play. The key insights derived are that public opinion is not a neutral product, that the media is a powerful tool of manipulation, and that democratic participation requires constant vigilance against propaganda.

The implications of these findings are far-reaching. For example, understanding these mechanisms is crucial for resisting manipulative advertising campaigns and political rhetoric. By becoming aware of the techniques used to shape our beliefs, we can cultivate a more critical and skeptical approach to information. This understanding also calls for promoting media literacy, encouraging a diversity of perspectives, and supporting independent journalism. Moreover, it highlights the need for open discussions about transparency, ethics, and the responsibilities of those who shape public opinion.

One could argue that critical awareness of propaganda techniques leads to cynicism and disengagement. However, a deeper understanding can empower citizens to be more discerning consumers of information, not necessarily to reject all information but to evaluate it critically. The true danger lies not in cynicism, but in naiveté. By acknowledging the challenges, we can foster a more informed and engaged citizenry, better equipped to navigate the complex political landscape.

Recognizing the pervasive influence of these techniques is the first step toward reclaiming agency over our own beliefs and participating more meaningfully in the democratic process. Now, let's explore how this manufactured consent manifests itself in the context of media ownership and its impact.

The Illusion of Choice: Media Manipulation and Its Impact

The subtle currents of influence that shape our understanding of the world continue to evolve, transforming with the technological landscape. Today, we are confronted not merely with overt propaganda, but with a sophisticated orchestration of information designed to create the illusion of autonomy within a system of carefully curated choices. This is particularly evident in the realm of media, where the proliferation of platforms and content, ironically, often narrows the scope of genuine understanding.

At the heart of this phenomenon lies the manipulation of our perception of choice. The contemporary media environment, often presented as a diverse and democratized space, is frequently characterized by homogenization. Algorithms, designed to maximize user engagement, often reinforce pre-existing biases, creating "echo chambers" and "filter bubbles." These digital spaces, as described by Eli Pariser, function as personalized universes, where we are primarily exposed to information that confirms our existing beliefs (Pariser, 2011). This creates the illusion of a vibrant and varied media landscape, while simultaneously limiting exposure to alternative viewpoints.

This reinforces the argument presented by Jean Baudrillard in Simulacra and Simulation. He theorizes that the contemporary world has moved beyond the real, into a realm of hyperreality, where simulations and representations have supplanted the actual (Baudrillard, 1994). In this context, the media’s role shifts from representing reality to constructing it. The news, entertainment, and even social interactions we encounter are increasingly mediated, pre-packaged, and designed to elicit specific emotional responses. This can lead to a form of "manufactured consent," a term that describes the process by which individuals are subtly led to accept the dominant narratives and perspectives of those in power, even when those narratives may not be in their best interests.

“The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true.”

— Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and SimulationFurthermore, the pervasiveness of commercial interests within the media further complicates the issue. Corporate ownership and advertising revenue significantly influence the types of stories that are told, the perspectives that are presented, and the issues that are prioritized. As Noam Chomsky articulated, the media landscape is subject to systemic biases that privilege certain voices and perspectives over others, serving the interests of the powerful (Chomsky & Herman, 1988). This often results in the marginalization of dissenting viewpoints and critical analysis, further solidifying the illusion of choice.

Imagine a scenario where a person, we'll call her Sarah, believes she is making informed choices about her news consumption. She follows a variety of news outlets on social media, reads articles from different perspectives, and even actively seeks out dissenting opinions. However, unbeknownst to Sarah, a powerful tech company controls the algorithms that determine the content she sees. These algorithms prioritize articles that align with her pre-existing biases, subtly downplaying content that challenges her views. Furthermore, sponsored content, disguised as legitimate news, subtly promotes a particular political agenda, further reinforcing her beliefs. Even with her best intentions, Sarah is trapped in a carefully constructed echo chamber, reinforcing the illusion that she has a wide range of choices, while, in reality, her perception of the world is being heavily manipulated. This illustrates how sophisticated control can work, even when individuals believe they are acting independently and with agency.