The Silent Cataclysm

How Urbanization’s Relentless Roar is Rewiring the Human Brain

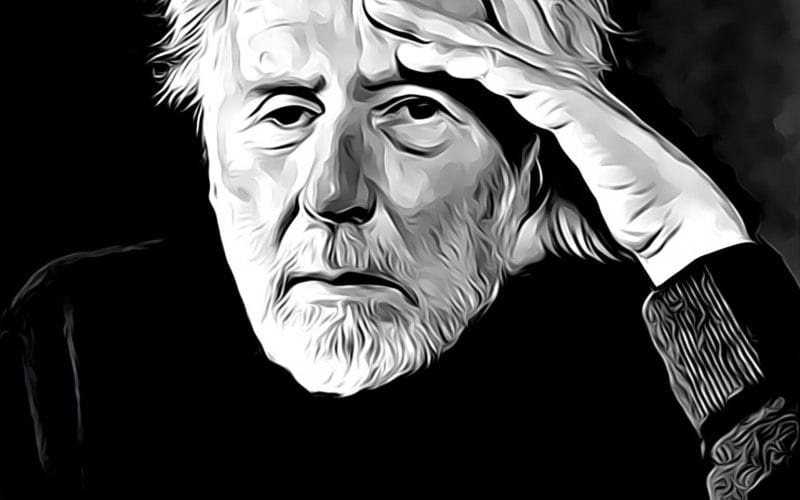

The Great Quieting: How the Loss of Our ‘Soundscapes’ is Rewiring Our Brains is a concept introduced by Canadian composer and environmentalist R. Murray Schafer, focusing on the significant transformation of our auditory environments due to urbanization and technological advancement.

This phenomenon encapsulates the shift from rich natural soundscapes to increasingly homogenized urban noise, highlighting concerns regarding the psychological and cultural impacts of diminishing sound diversity. As global urban populations surge, unique acoustic markers of nature are being replaced by monotonous industrial sounds, which has profound implications for human health and well-being.

The earth has music for those who listen.

George Santayana

Schafer’s work, particularly in acoustic ecology, emphasizes the importance of soundscapes in shaping our perception and interaction with the environment. He categorizes sounds into biophony, geophony, and anthrophony, asserting that the intricate relationships between these elements are critical for cultural memory and identity. The decline of traditional soundmarks—sounds unique to specific locations—alongside the rise of “schizophonia,” or the detachment of sounds from their original contexts, reveals a growing disconnection from our auditory heritage. This cultural shift raises alarms over the loss of meaningful sonic experiences, which Schafer argues is essential for psychological well-being.

The Great Quieting also serves as a reflection of society’s evolving relationship with silence, often perceived as uncomfortable in modern contexts. As the restorative power of quietude diminishes in urban settings, many individuals struggle with anxiety and discomfort in the absence of sound. In response, urban planners and researchers advocate for integrating acoustic considerations into urban design, promoting healthier soundscapes that enhance quality of life. This movement aims to address the adverse effects of noise pollution, foster community connections, and restore cultural identity through meaningful auditory experiences.

Ultimately, the discourse surrounding The Great Quieting underscores the urgent need to re-evaluate our acoustic environments, recognizing that sound is not merely a backdrop but a vital component of our mental and emotional health. As society continues to grapple with the implications of urban noise, there lies potential for transformative initiatives that could reintegrate the beauty of diverse soundscapes into our daily lives, thus enriching both personal and communal experiences.

Historical Context

The concept of soundscapes has evolved significantly, particularly in relation to urban environments and cultural memory. In historical districts, soundscapes have been recognized as vital indicators of authenticity and cultural identity, providing insights into the social and aesthetic meanings of different eras and communities. The traditional sounds associated with specific historical events serve as living archives that transmit cultural memory across generations, reflecting a community’s lived experiences.

As urbanization has progressed, many of these sounds have been lost, prompting discussions about the implications for cultural heritage. The disappearance of sounds, such as the calls of traditional street vendors, highlights a growing concern over cultural loss in the face of modernization. This shift has led to initiatives aimed at soundscaping, where efforts are made to preserve and reintroduce culturally significant sounds, ensuring that connections to the past are not completely severed.

The historical understanding of soundscapes also intersects with the emerging awareness of noise pollution and its effects on human health. Recent studies have shifted focus from merely addressing noise pollution to a broader consideration of urban soundscapes, which includes both natural and anthropogenic sounds. This holistic approach enables urban planners to assess and design urban spaces that not only mitigate adverse noise effects but also enhance the auditory environment by integrating natural sounds and fostering a more stimulating urban atmosphere [ 5-].

In addition, the integration of interactive soundscapes into urban planning signifies a new paradigm in how cities perceive their acoustic environments. Such initiatives encourage public engagement and co-creation, fostering a greater appreciation for the sonic heritage that shapes urban life. This growing recognition of the importance of sound in historical and contemporary contexts reflects an ongoing evolution in our understanding of cultural memory and identity, as articulated in the works of scholars such as Jan Assmann.

Key Concepts in Acoustic Ecology

Acoustic ecology is a multidisciplinary field that explores the relationship between humans and their acoustic environment, particularly how sound influences our perception and interaction with the world. It draws upon various concepts that help characterize soundscapes and their significance in both ecological and cultural contexts.

Soundscape Definition

The term “soundscape” refers to the total acoustic environment of a particular place, encompassing all sounds, from natural to man-made, that can be heard in that location. Soundscapes are shaped by the interactions between various elements, including biophony (sounds produced by living organisms), geophony (natural sounds from the environment), and anthrophony (sounds produced by human activities). R. Murray Schafer, a key figure in this field, famously described a soundscape as a collection of sounds, likening it to a painting composed of visual elements.

Key Components of Soundscapes

Schafer identified several important components within soundscapes:

Keynote Sounds: These are background sounds that are often overlooked but form the foundation of a soundscape. For instance, the constant hum of traffic in urban areas or the sound of wind in rural locations serves as a keynote for those environments.

Sound Signals: These foreground sounds are intended to be heard and convey specific information, such as bells, sirens, or announcements.

Soundmarks: Unique sounds that characterize a specific place, similar to visual landmarks. A soundmark could be the chime of a particular clock tower or the call of a native bird.

Hi-Fi and Lo-Fi Soundscapes

Schafer introduced the concepts of “hi-fi” and “lo-fi” soundscapes to describe the quality of acoustic environments.

Hi-Fi Soundscapes: Characterized by a favorable signal-to-noise ratio, allowing listeners to discern discrete sounds clearly amidst low ambient noise. Such environments enable a deeper auditory experience, similar to how rural landscapes provide long-range visual perspectives.

Lo-Fi Soundscapes: In contrast, lo-fi soundscapes exhibit high levels of ambient noise, obscuring individual sounds and creating a “Sound Wall” effect. This phenomenon, common in urban areas, diminishes the listener’s ability to engage with their acoustic surroundings.

The shift from hi-fi to lo-fi soundscapes reflects broader changes in human perception and interaction with the environment, as urbanization alters the acoustic landscape significantly.

Human Health and Environmental Impact

Noise pollution poses serious risks to both human health and wildlife. Excessive noise exposure can lead to hearing loss, stress, insomnia, and even cardiovascular issues. Wildlife is similarly affected; persistent loud noises can disrupt communication and alter behavior, leading to changes in community structure and species distribution. As urban areas expand, it becomes increasingly vital to consider the acoustic dimensions of planning and development to mitigate these effects and foster healthier environments for both humans and wildlife.

Noise is a pollution of the air, and it is a pollution of the mind.

Jacques Attali

By understanding these key concepts, researchers and practitioners in acoustic ecology can better appreciate the intricate relationship between sound, place, and our overall well-being.

The Great Quieting Phenomenon

The Great Quieting refers to a significant shift in the acoustic environment experienced globally, characterized by the diminishing presence of natural soundscapes and the rise of urban noise. This phenomenon is closely linked to urbanization and technological advancements, leading to a homogenization of soundscapes in cities around the world. As the global population continues to migrate from rural areas to urban centers—rising from 3% in 1800 to an estimated over 60% by 2025—the unique soundmarks of nature are increasingly replaced by the monotony of industrial and electronic sounds.

Nature vs. Urban Soundscapes

Despite the perception that natural environments are silent, they are often vibrant with the sounds of wildlife and natural processes. However, as urban areas expand, this richness is overshadowed by the relentless noise of city life. In many urban settings, such as Melbourne, familiar sounds like trams have become symbols of the city’s acoustic identity, yet they too suffer from a lack of character due to the forces of homogenization. This shift impacts our emotional and psychological relationship with sound, where quiet, once associated with tranquility, is now often perceived as boring or isolating.

Cultural and Technological Impacts

The Great Quieting also reflects historical transformations in society’s relationship with sound. The evolution of music—from nature-inspired compositions to those incorporating industrial and electronic elements—mirrors these changes, suggesting a growing disconnect from natural soundscapes. Furthermore, modern technologies, including recording and broadcasting, have transformed how we create and experience sound, leading to “schizophonia,” where sounds become detached from their original contexts. This detachment may contribute to the loss of cultural identity in urban environments, as unique acoustic signatures are replaced by uniform soundscapes shaped by technology.

Silence and Its Significance

Silence, as emphasized by R. Murray Schafer, is an essential component of the soundscape, offering a restorative counterpoint to the overwhelming noise of modern life. Schafer posits that silence is not merely the absence of sound, but a vital element necessary for appreciating meaningful sounds and maintaining acoustic health. As opportunities for silence diminish in urban settings, many individuals experience discomfort or negative associations with quiet, reflecting a societal trend that undervalues the importance of silence in our acoustic environments.

Silence is not the absence of something but the presence of everything.

Gordon Hempton

Future Directions

Looking forward, the future of urban soundscapes presents both challenges and opportunities. As cities implement strategies for acoustic urbanism to combat noise pollution and enhance quality of life, there is potential for developing soundscapes that are not only quieter but also more reflective of cultural identity. The integration of new technologies, such as electric vehicles and noise-canceling innovations, could reshape our auditory experiences, highlighting the need for a thoughtful approach to sound design in urban planning.

Implications of the Great Quieting

The phenomenon known as the Great Quieting has significant implications for both individual well-being and broader societal dynamics. This shift in our auditory environment