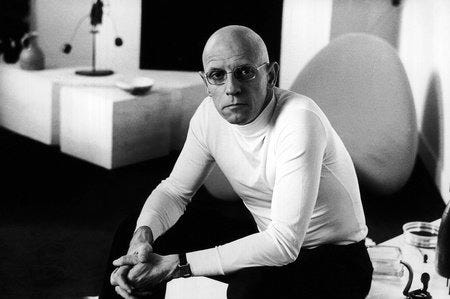

The Regime of Truth: Foucault’s Unheeded Warning That Knowledge Itself is a System of Control

We live within a complex architecture of rules, norms, and accepted truths, often believing we navigate this world as free agents. Yet, the French philosopher Michel Foucault issued a chilling prophecy that continues to haunt the modern age: what we call “knowledge” is not a neutral tool for liberation, but the most sophisticated instrument of power ever devised.

He argued that the very systems we use to define sanity, criminality, health, and reason are not objective discoveries but historical constructs—a “regime of truth” designed to classify, manage, and control populations. This is not the overt power of a king’s decree, but a subtle, pervasive force that operates through institutions, language, and even our own self-perception, shaping who we are long before we ever choose to be.

Foucault’s work is a critical examination of the interplay between power, knowledge, and social dynamics. His theories challenge traditional notions of knowledge as a tool for domination, positing instead that power and knowledge are inextricably linked and shaped by historical and cultural contexts. His analysis reveals the mechanisms of disciplinary control that govern societal norms and behaviors, emphasizing the process of normalization that defines what is considered “normal” or “abnormal” within various institutions. Through a Foucauldian lens, the work addresses the political implications of knowledge production and the ways in which truth is constructed and disseminated within specific discourses, reflecting broader societal interests and power structures. This perspective prompts a reevaluation of how individual subjectivity and resistance can emerge in response to these dynamics, highlighting the role of agency in navigating power relations.

The text also delves into the concept of context as a dynamic interplay of language and cultural factors, which shapes communication practices and influences the effectiveness of individuals’ insights in diverse settings. As such, it draws attention to the ethical considerations inherent in the dissemination of knowledge and the responsibilities of individuals in their communicative acts, particularly in contexts of social justice and equity. Overall, Foucault’s framework serves as a foundational lens through which to understand the challenges of being “right” in a world marked by competing narratives and power dynamics, inviting ongoing discourse and reflection on the implications for contemporary society.

Context

Understanding Context in Multilingualism

Context plays a crucial role in the study of multilingualism, as it shapes the way individuals engage with language and communicate in social settings. Rather than viewing context as a static backdrop to communication, it is more productive to understand it as a dynamic interplay of various discourses and social interactions. This perspective moves beyond Bateson’s metaphor of the “blind man and his stick,” which suggests a fixed environment. In reality, social contexts are fluid and involve active human agents who bring their own plans and agendas to conversations, significantly influencing the outcome of interactions.

The Role of Discourse in Context

Within any context of practice, different discourses coexist, each reflecting authority relations and varying degrees of significance. Fairclough (2003) highlights this “order of discourse,” which dictates how certain discourses can overshadow others based on the social and professional environments. For instance, a study of human resources professionals revealed that a managerialist, financial discourse dominated their communication practices, shaping the rhetoric of both their clients and their own positioning within the workplace.

Cultural Considerations in Contexting

The concept of “contexting,” as proposed by Hall, emphasizes the importance of shared information in communication, where both text and context mutually inform each other. Different cultures may assign varying degrees of importance to context versus text, leading to divergent communication styles. This highlights the idea that no language exists outside of its cultural context, underscoring the interdependent nature of language and culture in shaping communicative practices.

Historical Perspectives on Context

Foucault’s analysis of history also contributes to understanding context, suggesting that historical narratives modify forces rather than merely interpret them. By linking historical knowledge to power dynamics, he illustrates how the struggle for knowledge and authority plays a vital role in shaping contextual understanding. Thus, the political implications of historical knowledge become intertwined with the dynamics of communication and discourse, creating a complex web of influence that affects how context is perceived and utilized.

Main Themes

Power and Knowledge

A fundamental theme in Michel Foucault’s work is the intricate relationship between power and knowledge, encapsulated in the concept of ‘pouvoir-savoir’ (power-knowledge). Foucault argues that the two are not merely linked as tools and their operators; rather, they are intertwined in a way that the objectives of power and knowledge are inseparable, especially in the context of human subjects. This contrasts sharply with traditional notions where knowledge serves as an independent instrument of power. Instead, Foucault posits that in the pursuit of knowledge, one also exercises control, and vice versa, indicating that understanding is fundamentally shaped by power dynamics.

Power is not an institution, and not a structure; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name that one attributes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society.

Michel Foucault

Discipline and Normalization

Foucault explores the mechanisms of modern power, particularly through disciplinary control, which emphasizes the regulation of behavior and the enforcement of societal norms. This form of power focuses on what individuals fail to do (non-observance) and seeks to correct behaviors deemed deviant, a process he terms “normalization.” Unlike premodern punishment systems, which primarily judged actions as permissible or not, modern disciplinary systems impose detailed standards that categorize individuals as “normal” or “abnormal.” This normalization extends to various societal institutions, including education and healthcare, reinforcing the pervasive nature of disciplinary practices in everyday life.

Truth and Its Historical Context

Truth, as conceptualized by Foucault, is not a static entity waiting to be discovered but rather a dynamic construct influenced by historical contexts and power relations. He asserts that truth is an event that occurs within specific societal discourses, shaped by various techniques and power mechanisms. This means that each society has its own “regime of truth,” and knowledge cannot exist outside the circulation of power. Foucault emphasizes that the pursuit of truth is inherently linked to the exercise of power, as the production of knowledge involves both the creation and enforcement of truths that reflect particular societal interests.

Subjectivity and Resistance

In Foucault’s analysis, the formation of individual subjectivity is deeply intertwined with power relations. He challenges the notion that subjects can be simply opposed to power; instead, he suggests that individuals are both products and participants in these power dynamics. Resistance is, therefore, an integral part of power relations, as individuals navigate and contest the norms imposed upon them. Foucault’s work highlights how individuals internalize disciplinary practices, which, while confining, also provide avenues for resistance and agency.

Where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power.

Michel Foucault

The Role of Language and Discourse

Foucault’s exploration of language and discourse further illustrates his views on power and knowledge. He argues that discourse shapes our understanding of reality and constructs categories of thought, influencing how individuals perceive themselves and others. In this framework, language becomes a site of power where societal norms and values are articulated and reinforced. Moreover, the concept of correctness in language reflects broader societal beliefs about morality and citizenship, illustrating the power dynamics embedded within linguistic practices.

Structure of the Work

Methodological Framework

In examining Michel Foucault’s work, it is essential to note his approach towards rights and power dynamics, which he articulates without aspiring to a unified theory. Foucault deliberately distances his writings from systematic theoretical frameworks, opting instead for an “analytics” of power that explores the intricate relations of domination and resistance within societal structures. This methodology encompasses a critical analysis of how power and knowledge interact, presenting power as both decentralized and dynamic.

Conceptual Foundation

Foucault’s exploration of social formations reveals a duality where visibility and statements create strata that constitute knowledge-being. He posits that speaking and seeing operate independently, highlighting a significant gap that shapes the nature of discourse and the formation of subjectivity within power relations. This perspective allows for a deeper understanding of how bodies and identities are formed through historical and functional interactions with power.