The People Versus The Elite & The Challenge to Governance

Have you ever felt like there's a widening gap between you, your community, and the people making the decisions that shape your life? That the system feels rigged, that a distant 'elite' seems to care more about global agendas or their own interests than the everyday struggles of ordinary people?

If you recognize that feeling, you're touching the raw nerve that fuels the most disruptive political phenomenon of our time: populism.

But what is populism, really? Is it just anger? A simplistic cry from the fringes? Or is it something deeper, a fundamental challenge to how we are governed?

In this article, we're going to cut through the noise. We will define populism not as a dirty word, but as a powerful worldview that pits 'the pure people' against 'the corrupt elite'. We'll uncover why this story resonates so strongly today – from economic anxieties to cultural shifts. And importantly, we'll show you this isn't new; it's a force with deep historical roots that has challenged governance before.

Understanding populism is crucial, because whether you support it or fear it, it is reshaping the future of democracy right now.

Defining the Core Conflict

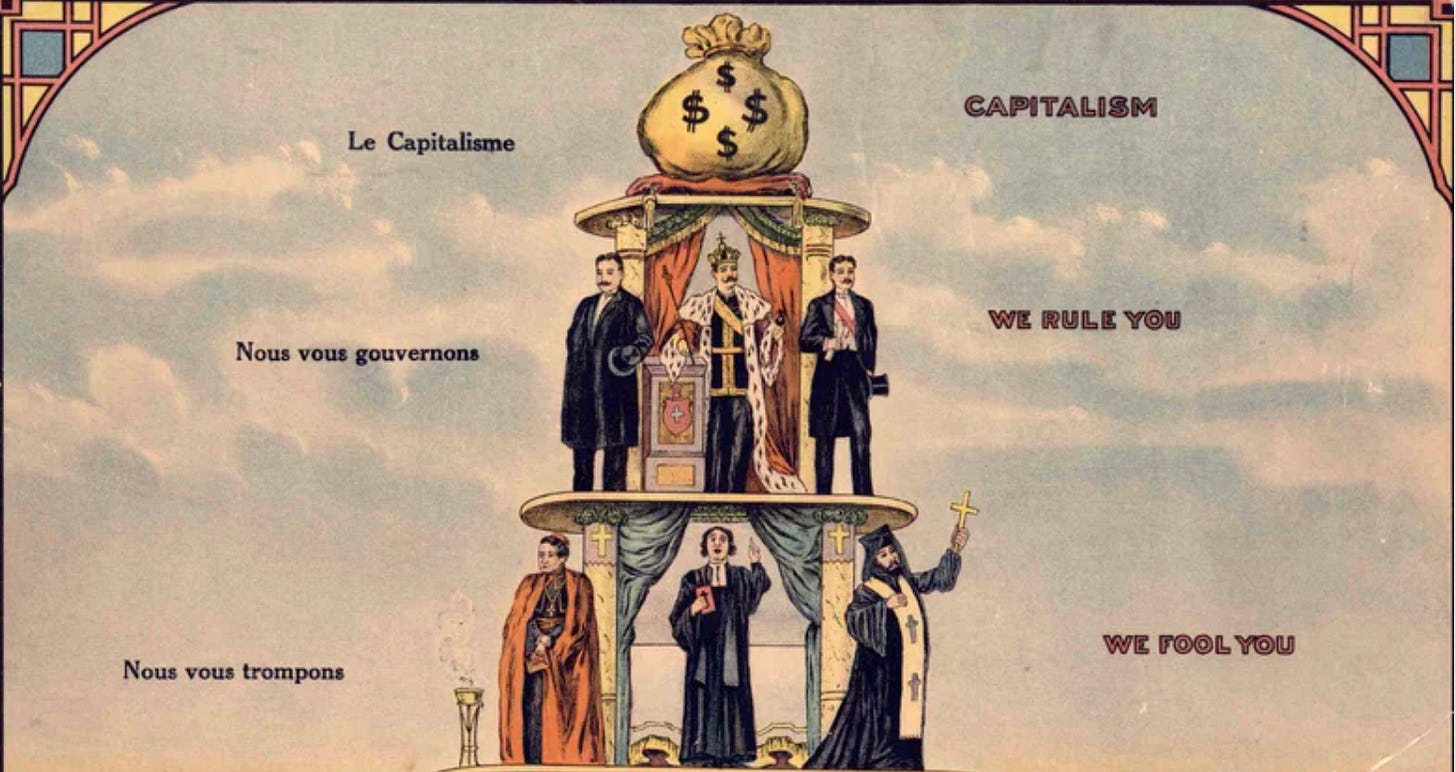

Let's break down what populism is, not just as a buzzword thrown around in the news, but as a distinct political ideology. At its core, populism operates on a fundamental moral division of society. It posits that there are two homogenous, and antagonistic, groups: 'the pure people' and 'the corrupt elite'.

This isn't just a difference of opinion or policy. It's a moral binary. The populist narrative sees 'the people' – often defined vaguely but typically centered on the 'common man', the working class, the traditional community – as inherently good, honest, and possessing true wisdom about the nation's needs. They are the victims of a system rigged against them.

Opposing them is 'the elite'. This 'elite' is portrayed as a cohesive, often conspiratorial, group that controls the levers of power – political institutions, the media, academia, global finance – and uses that power for their own benefit, not for the good of 'the people'.

They are seen as corrupt, out of touch, self-serving, and often disloyal to the nation, perhaps prioritizing global agendas or abstract ideals over the concrete well-being of their own citizens. The populist leader then steps forward claiming to be the authentic voice of 'the people', bypassing traditional institutions and speaking directly against this corrupt elite.

The Anxieties Fuelling the Fire (Why Now?)

So, why does this narrative resonate so powerfully today? Why, across continents and cultures, are we seeing this surge in movements that adopt this 'people versus elite' framework?

One major driver is undeniable: deep-seated economic anxiety. For decades, many communities in developed nations have watched industries relocate, jobs disappear, and wages stagnate while the cost of living continues to climb. Globalization, while creating immense wealth overall, has also created clear winners and clear losers.

Those working in sectors exposed to international competition, those in areas dependent on traditional manufacturing, often feel left behind. They see statistics about national GDP growth or stock market highs that don't reflect their reality of precarious employment, mounting debt, or diminishing opportunity. This economic frustration is fertile ground for populism, which often scapegoats the 'elite' – whether global financiers, trade negotiators, or even immigrant labor – as responsible for their hardship.

But it's not just economics. There's a profound sense of cultural dislocation at play. Societies are changing rapidly. Traditional values are being questioned, demographic landscapes are shifting, and debates over identity, language, and history can feel incredibly divisive.

For many, particularly in communities that feel their traditional way of life is under threat or simply no longer respected, this cultural shift creates a potent anxiety. They feel like outsiders in their own country, sometimes explicitly told that their beliefs or heritage are outdated or even harmful. The populist leader often taps into this by promising a return to a perceived golden age of cultural homogeneity or national pride, framing cultural anxieties as another betrayal by the 'liberal elite' who they accuse of undermining traditional values or promoting 'political correctness' at the expense of common sense.

Add to this a pervasive sense of political disenfranchisement. For a growing number of people, the established political system feels unresponsive, distant, and captured by special interests. They see politicians making promises they don't keep, scandals go unpunished, and policies seeming to benefit corporate donors or global bodies more than the constituents they were elected to serve.

The revolving door between government and lobbying, the influence of big money in campaigns, the perceived inability of mainstream parties to understand or address ordinary people's problems – all of this erodes trust in democratic institutions. Populism thrives by validating this distrust, presenting the existing political structure as part of the corrupt elite and offering a radical alternative that promises to 'drain the swamp' or 'give power back to the people'.

Finally, there's the yearning for national sovereignty in an increasingly globalized world. Supranational organizations, international treaties, and global markets can feel like forces that strip away a nation's ability to control its own destiny, its own borders, its own laws. Populist movements often capitalize on a desire to reclaim that control, arguing that national interests must come first, and that decisions affecting the country should be made by elected national representatives accountable *only* to the people of that nation, not to distant bureaucrats or international bodies.

These interwoven threads weave together to create the potent tapestry of populist appeal. It's a response, often angry and disruptive, to the feeling that the established order has failed the very people it was supposed to serve. And while contemporary populism feels urgent and new, this dynamic of 'the people' rising against 'the elite' to challenge governance has deep roots in history.

Here are some of the core anxieties driving modern populism:

Deep-seated economic insecurity and perceived unfairness from globalization.

Cultural dislocation and anxiety over rapid societal changes and traditional values.

Political disenfranchisement and distrust of established institutions.

A desire to reclaim national sovereignty from global forces.

Not New: Populism's Historical Echoes

Now, we've dissected the potent brew of economic anxiety, cultural friction, political distrust, and the pull of national sovereignty that fuels populism today. But to truly understand its enduring power, to see why it keeps bubbling up and challenging established power structures, we have to look back.

Because this isn't a new script written for the 21st century. It's a recurring drama in the history of democracy, played out whenever segments of 'the people' feel alienated by 'the elite'.

Let's rewind to the early 19th century in the United States. As the young nation expanded westward, a new breed of American was emerging – frontiersmen, farmers pushing into new territories, urban laborers in burgeoning cities. These were people who felt little connection to the established, aristocratic elite of the original colonies – the landed gentry, the powerful merchants, the lawyers and politicians from families long in positions of influence.

Enter Andrew Jackson. Jackson, a military hero but a political outsider from the frontier state of Tennessee, galvanized these feelings. His movement, known as Jacksonian Democracy, was a direct assault on the perceived 'elite'. Who were they? The prime target was the Second Bank of the United States.

Jackson and his followers saw this national bank – a powerful private corporation chartered by the federal government with significant control over the nation's credit and currency – as an instrument of the wealthy elite, benefiting speculators and merchants in Eastern cities at the expense of ordinary farmers and laborers. Jackson famously called it a "monster" that concentrated wealth and power in the hands of a few.

Jacksonian populism championed the 'common man'. It distrusted complex institutions and favored direct democracy, advocating for things like expanded voting rights (for white men, importantly, reflecting the era's limitations), and rotation in office to prevent the growth of a permanent governing class. The rhetoric was fiery: pitting the virtuous, hard-working people against the privileged, corrupt few who manipulated the system from their gilded cages. Jackson's presidency saw the dismantling of the National Bank, a monumental victory for the populist forces against the established financial elite. Sound familiar in an age where distrust of big banks and financial institutions is rampant? The echoes are undeniable.

Fast forward to the late 19th century, the Gilded Age. America had industrialized rapidly, but this growth came at a cost for many. Farmers, in particular, faced crushing debt, falling crop prices, and exploitative practices by powerful monopolies like the railroads, which charged exorbitant rates to transport goods, and the banks, which controlled credit and loans. They felt squeezed from all sides, ignored by a political system that seemed beholden to the interests of wealthy industrialists and financiers – the new Gilded Age elite.

This era gave rise to the Populist Party, also known as the People's Party. This was a movement born out of farmer alliances and labor groups, explicitly positioning themselves as the voice of 'the people' – the producers, the workers, the common folk – against the powerful 'elite' of Wall Street and Washington D.C.

Their platform was radical for its time, advocating for policies like government ownership of railroads and telegraphs (to break the power of monopolies), a graduated income tax (to make the wealthy pay their fair share), and crucially, reforms to the monetary system – the free coinage of silver – which they believed would inflate prices and ease the debt burden on farmers.

Their rhetoric was a clear 'people versus elite' narrative. They spoke of hardworking Americans being oppressed by 'money power', by 'barons of industry', by corrupt politicians in the pockets of big business. Leaders like Mary Elizabeth Lease urged farmers to speak out:

raise less corn and more hell!

William Jennings Bryan, though running as a Democrat in 1896 and incorporating populist themes, delivered his famous "Cross of Gold" speech railing against the gold standard and declaring:

You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

These historical examples aren't just dusty footnotes. They reveal a fundamental pattern: when significant segments of the population feel unheard, economically exploited, or culturally sidelined by those in power, the appeal of a leader or movement that claims to speak *directly* for 'the pure people' against 'the corrupt elite' becomes incredibly powerful.

The targets change – from banks and railroads to globalists and multinational corporations – but the core dynamic of an alienated 'people' challenging a perceived 'elite' remains remarkably consistent. This historical perspective helps us understand that while today's populism faces unique modern challenges like social media and a hyper-connected world, its roots tap into a very old and very powerful grievance.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

The Challenge to Governance

So, we've explored populism not just as political noise, but as a fundamental belief system that divides the world into 'the pure people' and 'the corrupt elite'. We've seen how it thrives on very real anxieties – the economic pain, the cultural shifts, the feeling of being politically ignored, the desire for national control in a borderless world.

And crucially, we've understood that this isn't a sudden aberration, but a powerful, recurring challenge to established governance that has surfaced throughout history, adapting its form but keeping its core narrative.

Populism, in its many guises, forces us to confront deep questions about who holds power, who benefits from the system, and whose voice truly counts. It challenges the very foundations of representative democracy and global cooperation.

As you look at the political landscape around you today, consider this: Are the conditions that fuel populism – the anxieties, the divisions, the distrust – being addressed? Or are they deepening? What happens to democracy when a significant portion of the population feels permanently alienated from its leaders and institutions? And how do we distinguish between a legitimate cry from the people for change, and the potentially destructive forces that populism can unleash?

Think about those questions. Engage with them. Because understanding populism isn't just about understanding politics; it's about understanding the powerful currents reshaping our world.

https://open.substack.com/pub/masroorshah/p/a-legend-from-buddhism?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=643hzq

Buddhism

https://open.substack.com/pub/marcospaulocandeloro/p/thetotalitarianismoftheballotbox?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=zvhi