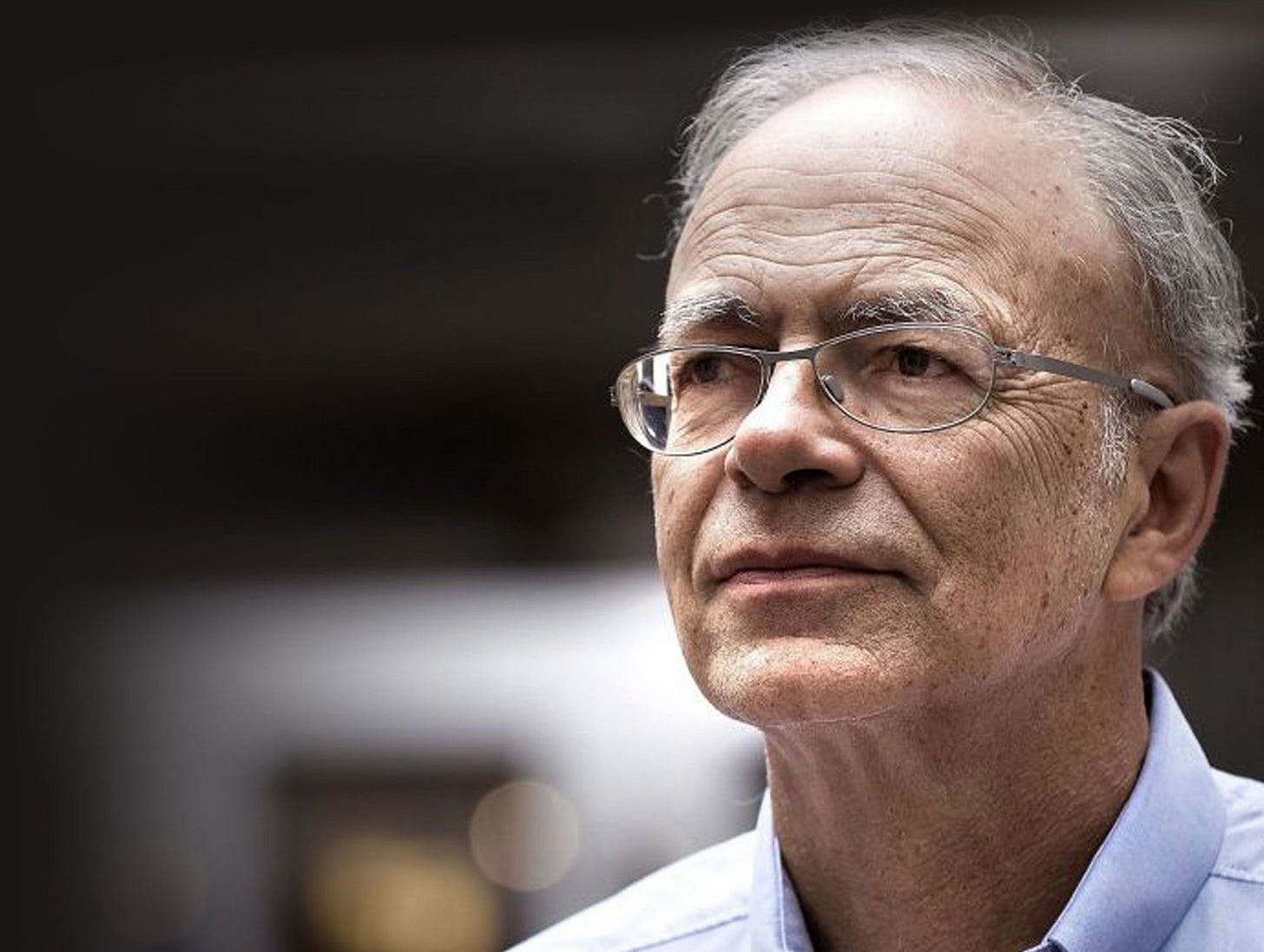

The Most Good You Can Do: A Deep Dive into Peter Singer's Effective Altruism

Effective altruism, a philosophical and social movement spearheaded by thinkers like Peter Singer, calls for a radical re-evaluation of our moral obligations. It challenges us to think critically about how we can use our resources – time, money, skills – to do the most good possible. This isn't just about being "nice" or feeling good; it's about applying reason and evidence to identify and address the world's most pressing problems with maximum impact. This essay will delve into the core principles of effective altruism, exploring its philosophical foundations, practical applications, and the criticisms it faces.

The Utilitarian Roots: Maximizing Happiness and Minimizing Suffering

At its heart, effective altruism draws heavily from the utilitarian tradition, most notably the ideas of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Utilitarianism posits that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. Singer's contribution lies in extending this principle globally and practically. He argues that we have a moral obligation to alleviate suffering wherever it exists, regardless of geographical distance or social proximity. This isn't just a matter of personal preference; it's a fundamental ethical imperative.

"If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it." - Peter Singer, "Famine, Affluence, and Morality"

This quote from Singer's seminal essay, "Famine, Affluence, and Morality," encapsulates the core argument. He uses the analogy of seeing a child drowning in a shallow pond. Most people would agree that we have a moral duty to wade in and save the child, even if it means getting our clothes muddy. Singer argues that the distance between us and those suffering from extreme poverty or preventable diseases is morally irrelevant. Modern communication and transportation have effectively shrunk the world, making it possible for us to make a tangible difference in the lives of people we may never meet.

Beyond Charity: Evidence-Based Giving and Problem Prioritization

Effective altruism isn't simply about donating to *any* charity; it's about donating to the *most effective* charities. This requires rigorous analysis and evidence-based decision-making. Organizations like GiveWell meticulously evaluate charities based on their impact, cost-effectiveness, and transparency. They look for charities that can demonstrate a proven track record of improving lives, often focusing on interventions that are relatively inexpensive but yield significant results, such as insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent malaria or deworming medication for children.

Furthermore, effective altruists prioritize problems based on their scale, neglectedness, and solvability. Scale refers to the number of people affected by a problem; neglectedness refers to how much attention and resources are already being devoted to addressing the problem; and solvability refers to how amenable the problem is to effective intervention. For example, global poverty, preventable diseases, and existential risks (such as climate change or nuclear war) are often considered high-priority problems because they affect a large number of people, are relatively neglected compared to other issues, and have potential solutions that can be implemented effectively.

Career Choice and the Path to Impact

Effective altruism extends beyond charitable giving; it also influences career choices. Organizations like 80,000 Hours provide guidance on how to choose a career that maximizes positive impact. This might involve working directly for an effective charity, conducting research on global problems, or pursuing a high-earning career and donating a significant portion of one's income to effective causes. The key is to strategically leverage one's skills and resources to make the biggest difference possible.

The idea of "earning to give" is a particularly controversial aspect of this approach. It suggests that individuals might be able to do more good by pursuing high-paying careers in finance or technology and donating a substantial portion of their earnings to effective charities than by working directly for a non-profit organization. This strategy raises ethical questions about complicity in potentially harmful industries, but its proponents argue that the net positive impact outweighs the moral compromises involved.

Criticisms and Challenges

Effective altruism is not without its critics. Some argue that it is overly rationalistic and neglects the importance of emotions, relationships, and personal values. Others contend that its focus on quantifiable outcomes can lead to a narrow and distorted view of what constitutes "good." Critics also raise concerns about the potential for effective altruism to reinforce existing power structures and inequalities, particularly if it relies heavily on the expertise of privileged individuals and institutions.

One common criticism is that effective altruism can be demanding and guilt-inducing. The constant pressure to do more good can lead to burnout and a sense of moral inadequacy. Furthermore, some argue that effective altruism overlooks the importance of systemic change and focuses too much on individual actions. While individual donations and career choices can make a difference, addressing the root causes of global problems often requires broader political and social reforms.

Another challenge is the difficulty of accurately measuring the impact of different interventions. Even with rigorous evaluation methods, it can be hard to definitively prove that one charity is more effective than another. Furthermore, the long-term consequences of interventions are often difficult to predict, and unintended negative consequences can arise. The field of impact evaluation is constantly evolving, and effective altruists must remain vigilant in adapting their strategies based on new evidence and insights.

A Framework for Ethical Action

Despite its limitations and challenges, effective altruism provides a valuable framework for ethical action in a complex and interconnected world. It encourages us to think critically about our moral obligations, to prioritize the needs of others, and to use reason and evidence to make a positive impact. While not a perfect solution, it represents a significant step forward in our quest to create a more just and compassionate world. By embracing the principles of effective altruism, we can move beyond simply feeling good about doing something and strive to do the *most* good we can.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of effective altruism hinges on its ability to adapt, learn, and incorporate feedback from diverse perspectives. It requires a willingness to challenge assumptions, to question established practices, and to constantly refine its approach based on new evidence and insights. Only through such a process of continuous improvement can effective altruism realize its full potential to alleviate suffering and promote human flourishing.

Effective altruism, at its core, is a call to action, a challenge to complacency, and a reminder that we all have the power to make a difference.

By thoughtfully considering the plight of others and applying rigorous analysis to our actions, we can strive to create a world where compassion and effectiveness go hand in hand.

It is not just about doing good; it is about doing the *most* good possible, and in doing so, transforming ourselves and the world around us.

In a world saturated with suffering and injustice, can we truly afford to ignore the imperative to maximize our positive impact, or is the pursuit of the most good we can do not just a moral aspiration, but a pressing existential necessity?