The Iron Law of Elites: Why the Powerful ALWAYS Stay in Charge?

You’ve seen it, haven’t you? That nagging feeling when you observe the world, watch the news, or simply scroll through your feed. There’s a constant churn, a cycle of new faces, new policies, new promises. Yet, beneath the surface, the names change, but the game often feels eerily the same. The powerful remain powerful, the influential still hold sway, and those at the top seem to possess an almost uncanny ability to endure, no matter the political earthquake or social tremor.

It’s a phenomenon that transcends nations, ideologies, and historical epochs. A persistent reality that whispers a disquieting truth: some individuals, some groups, seem destined to rule. But why? Is it simply luck, superior intellect, or something more fundamental baked into the very fabric of human organization?

This isn’t a conspiracy theory. It’s an observation rooted in centuries of political thought and sociological analysis, a concept often referred to as “The Iron Law of Elites.” It suggests that regardless of how a society begins, whether as a revolutionary movement promising equality or a monarchy claiming divine right, power will inevitably coalesce into the hands of a small, organized minority.

The Illusion of Meritocracy

We’re often told a comforting story: that society is a meritocracy. Work hard, be smart, innovate, and you too can rise to the top. And sometimes, individuals do. Horatio Alger stories punctuate our folklore, serving as beacons of hope and evidence that the system is fair. But look closer. For every singular story of ascent, how many remain tethered to their origins?

Do we truly believe that the most competent, the most ethical, or the most visionary are consistently the ones who reach and retain the pinnacles of power? Or is there another, more subtle mechanism at play, one that favors not just talent, but also inheritance, connections, ruthless ambition, and an inherent understanding of how power structures operate?

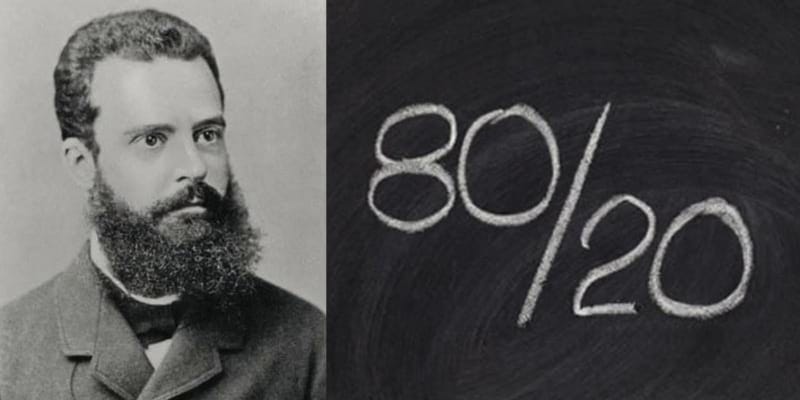

Vilfredo Pareto and the Circulation of Elites

One of the most profound thinkers to articulate this enduring truth was the Italian sociologist and economist, Vilfredo Pareto, in the early 20th century. Pareto wasn’t interested in moral judgments; he was an empirical observer. He noted that in every society, power, wealth, and influence always distribute unevenly, following what is sometimes called the “Pareto Principle” or the 80/20 rule, where a small percentage of people hold a large percentage of the resources or power.

More specifically, Pareto developed the theory of the “circulation of elites.” He argued that all societies are governed by an elite, a minority that rules, and a non-elite, the majority that is ruled. The critical insight, however, is that while elites may change, the *fact* of elite rule does not. When an old elite decays or loses its grip—perhaps becoming too soft, too corrupt, or too resistant to change—it is not replaced by the masses, but by a new, more vigorous counter-elite.

Every society, whether it be a republic or a monarchy, is always governed by an elite, a minority of powerful individuals, who, by their superior qualities and influence, manage to rule the masses, even in a democratic regime.

— Vilfredo Pareto

He saw history as “a graveyard of aristocracies,” a continuous cycle of elites rising, ruling, decaying, and being overthrown by new elites. The nature of the elite might shift—from military to economic, from religious to intellectual—but the fundamental structure of a ruling minority remains constant. It’s a sobering perspective that challenges the romantic notion of “power to the people.”

The Mechanisms of Elite Perpetuation

How do these elites, once in power, manage to cling to it with such tenacity? It’s rarely through brute force alone, though that is always a last resort. Instead, a complex web of interwoven mechanisms ensures their continued dominance:

Control of Institutions: Elites strategically position their members or allies within key institutions: government bureaucracies, the judiciary, major corporations, universities, and crucially, the media. This allows them to shape policy, enforce laws, control information, and influence public discourse.

Resource Hoarding: Access to capital, land, education, and essential networks becomes concentrated. This creates a powerful advantage for their offspring and chosen successors, who benefit from generational wealth and connections, making it exceedingly difficult for outsiders to compete.

Ideological Hegemony: Elites don’t just control resources; they control ideas. They promote narratives, values, and worldviews that legitimize their power and often make alternative arrangements seem impractical, dangerous, or even unthinkable. Think of the pervasive belief that “there is no alternative” to the current economic system.

Co-optation and Exclusion: Exceptionally talented or charismatic individuals from the non-elite might be co-opted into the elite, neutralizing potential threats and refreshing the elite’s talent pool. Those who cannot be co-opted, or who pose a genuine threat to the established order, are systematically marginalized, delegitimized, or excluded from positions of influence.

This intricate dance ensures a self-reinforcing system, where power begets more power, and influence solidifies into a near-impenetrable fortress.

The Challenge of Disruption

To challenge an elite is not merely to challenge a few individuals; it is to challenge a deeply entrenched system designed for its own perpetuation. Revolutions often promise radical change, yet the historical record suggests that even the most fervent uprisings frequently result in the replacement of one elite with another, rather than the abolition of elite rule itself.

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.

— Lord Acton

The “Iron Law” suggests that the powerful, by their very nature, are driven to maintain their position, utilizing every available tool and strategy. They are often more organized, more unified in purpose (even amidst internal squabbles), and possess greater resources than any potential counter-force. The very nature of collective action, which is essential for challenging entrenched power, is inherently difficult to sustain and coordinate against a well-resourced and unified opposition.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

The Iron Law of Elites is not a call to despair, nor is it an excuse for apathy. Instead, it serves as a powerful analytical tool, stripping away comforting illusions and forcing us to confront a fundamental aspect of human societies. It reminds us that “the people” rarely rule directly; instead, they are always led, always governed, by some form of elite.

Understanding this law is crucial for anyone seeking genuine change. It means moving beyond simplistic notions of good versus evil leaders and instead focusing on the underlying structures, incentives, and mechanisms that allow elites to form, consolidate, and persist. The struggle, then, is not merely to replace bad leaders with good ones, but to continually interrogate the very nature of power itself, and to build systems that, if they cannot abolish elite rule entirely, can at least hold it more accountable, make it more permeable, and ensure its continuous, healthy circulation.