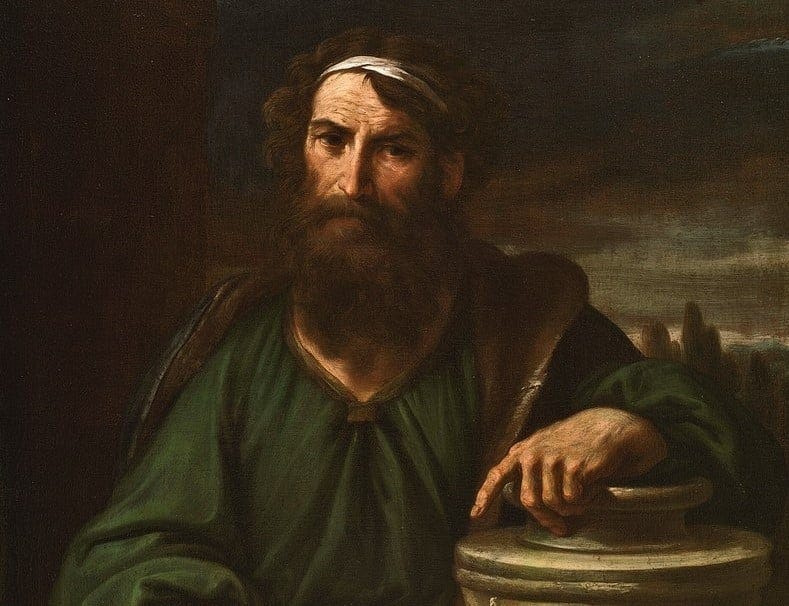

The Ghost of the Garden

Epicurus’s Unheeded Warning Against the Counterfeit Pleasures of Modern Life

In an age saturated with the frantic pursuit of fleeting highs and manufactured joys, the name Epicurus is often invoked as a ghost of indulgence—a philosopher king of hedonism. But this is a profound and dangerous misreading. The true teachings of the Athenian sage, cultivated in the quiet of his legendary garden, offer not a license for excess, but a chillingly relevant diagnosis of a society sick with anxiety, and a radical prescription for a life of profound tranquility built on the absence of pain, not the accumulation of stimulation.

An Ancient Philosophy for Modern Ills

Epicurus (341–271 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher whose teachings revolutionized the understanding of pleasure, advocating for a conception of happiness that contrasts sharply with hedonistic excess. He established his school in a garden in Athens, where he emphasized the pursuit of happiness through simple pleasures and mental tranquility rather than through indulgent lifestyles, which critics often associated with his philosophy. Epicurus defined pleasure as the absence of pain and anxiety, positing that true contentment arises from the fulfillment of natural desires and the cultivation of inner peace, thereby challenging the prevailing philosophical views of his time, particularly those of the Stoics and other contemporaries who prioritized virtue above pleasure.

Notably, Epicurus differentiated between kinetic pleasures—those resulting from fulfilling desires—and katastematic pleasures, which embody a state of tranquility free from disturbance. This distinction underpins his argument that while transient pleasures may provide temporary satisfaction, it is the cultivation of inner peace and moderation that leads to genuine happiness. His insights into the nature of desire further illuminate the path to a fulfilling life, as he categorized desires into natural and necessary, natural and unnecessary, and non-natural and unnecessary, arguing that true happiness stems from recognizing and satisfying only the essential desires.

Despite its practical and moral implications, Epicurean philosophy has often been misrepresented as a doctrine of unrestrained hedonism, overshadowing its core message of moderation and self-control. Critics have perpetuated misconceptions about the nature of pleasure, conflating it with indulgence while neglecting the nuanced understanding that Epicurus advocated, which prioritizes tranquility over excess. Furthermore, he contended that the complexities of language and thought can distort our understanding of pleasure and happiness, emphasizing the need for careful reflection in the pursuit of a good life.

Epicurus’s ideas continue to resonate today, presenting a counter-narrative to both ancient and contemporary philosophical discourses on happiness. By offering a framework for understanding pleasure as integral to ethical living and human fulfillment, his legacy remains relevant in modern discussions about well-being and the nature of a good life, challenging the oversimplified interpretations of hedonism that persist in popular thought.

Historical Context

Epicurus (341–271 BCE) emerged in a period of significant philosophical development in ancient Greece, characterized by the rise of various schools of thought, including Stoicism and Skepticism. His teachings, which emphasized the pursuit of happiness through simple pleasures and the cultivation of tranquility, stood in stark contrast to the prevailing philosophical norms of his time. While Stoics advocated for virtue and self-control as the highest goods, Epicurus argued that pleasure, defined as the absence of pain and anxiety, was the ultimate goal of life.

Epicurus founded his school in a garden on the outskirts of Athens, a setting that became a haven for his followers to engage in discussions about ethics, science, and the nature of happiness. This communal lifestyle was often misrepresented by critics, who depicted Epicurus and his followers as hedonistic libertines indulging in excesses. However, Epicurus himself led a life marked by simplicity, favoring modest pleasures such as bread, olives, and companionship over extravagant feasting.

This emphasis on simple living and mental tranquility positioned Epicureanism as a practical philosophy aimed at addressing the anxieties of daily life, particularly in a world rife with political instability and social upheaval.

The philosophical environment during Epicurus’s time was dominated by the influence of earlier thinkers such as Democritus, whose atomistic theories laid the groundwork for Epicurus’s natural philosophy. Epicurus adopted and adapted these ideas, integrating them into his own ethical framework that rejected superstition and divine intervention in human affairs. His approach to epistemology, ethics, and the nature of reality challenged traditional beliefs and encouraged a more empirical understanding of the world, promoting a philosophy based on observation and reason rather than dogma.

Moreover, the revival of interest in Epicurean thought in modern times has seen it reframed as a response to contemporary existential concerns, offering insights into the pursuit of happiness amidst the complexities of modern life. The perception of Epicureanism as a gastronomic philosophy overlooks its foundational principles, which advocate for contentment through moderation and understanding the nature of desire and fear. Thus, Epicurus’s legacy continues to resonate, presenting a counter-narrative to both ancient and modern philosophical discourses on happiness and the good life.

The Nature of Pleasure

Epicurus presents a nuanced understanding of pleasure, emphasizing that it is not merely the pursuit of indulgence or hedonistic excess. Instead, he defines pleasure as the absence of pain and the disturbance in the soul, asserting that true pleasure arises from sober reasoning and the fulfillment of basic desires rather than from transient indulgences. He categorizes pleasure into two primary types: kinetic and katastematic. Kinetic pleasures result from activities that fulfill desires but can lead to psychological distress, while katastematic pleasures represent a state of inner tranquility and the absence of pain.

The Role of Desire

Epicurus distinguishes between different types of desires, categorizing them as natural and necessary, natural and unnecessary, and non-natural and unnecessary. Satisfying natural and necessary desires, such as hunger and thirst, directly contributes to the health of both the body and the mind. Unnecessary desires, however, may lead to distractions from true happiness,