The Cloud Is A Lie

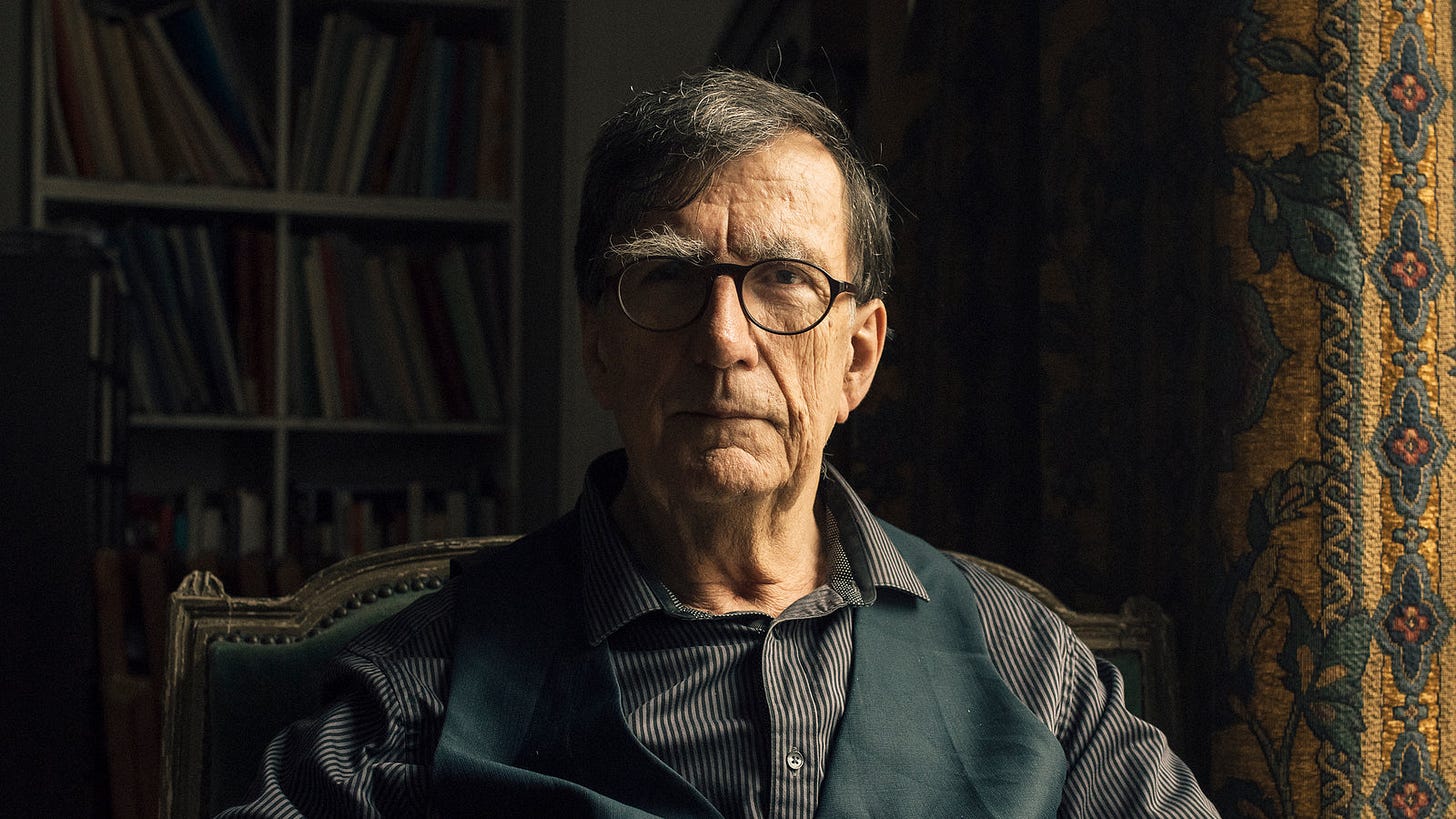

Bruno Latour and the Geopolitics of the Cable

Every time you upload a photo, save a document, or stream a movie, you are participating in a linguistic hallucination. We have collectively agreed to use a metaphor that is actively designed to deceive us: “The Cloud.”

The imagery is deliberate. It suggests something white, fluffy, and atmospheric. It implies that our digital lives are weightless, floating effortlessly above the messy realities of the earth in a realm of pure, ethereal logic. It frames the internet as a spirit—omnipresent, democratic, and untouchable.

This is the greatest magic trick of the twenty-first century.

If you were to actually visit the Cloud, you would not find the sky. You would find yourself in a windowless fortress in Northern Virginia, surrounded by the deafening roar of industrial air conditioning and the smell of ozone. You would see diesel generators the size of locomotives and armed guards patrolling the perimeter. The Cloud is not light; it is heavy. It burns coal. It drinks rivers of water. It occupies land.

The internet is not in the atmosphere; it is in the mud. And as the French philosopher Bruno Latour argued, ignoring the mud is a fatal political mistake.

The Parliament of Things

For centuries, sociology and philosophy have been obsessed with humans. We analyze voters, dictators, protestors, and CEOs. We treat the material world—the desks, the doors, the roads, and the wires—as the passive background scenery against which the human drama plays out.

Bruno Latour looked at this arrangement and called it arrogant. He proposed a radical shift in perspective known as Actor-Network Theory. His premise was simple yet disturbing: objects are not passive tools. They are actors.

Latour argued that you cannot understand how a society holds together by only looking at “social contracts” or laws. Laws are just words on paper. To make a law durable, you have to petrify it into matter. You have to delegate authority to an object.

Consider the “sleeping policeman,” or speed bump. A government could place a human officer on a street corner to enforce a speed limit, but that is expensive and humans get tired. Instead, the government pours concrete onto the asphalt. They transform a moral imperative—”do not drive fast”—into a physical obstacle.

There is no such thing as a society of humans; there are only societies of humans and non-humans.

— Bruno Latour

The speed bump is a political actor. It enforces the law without sleep, without bribery, and without mercy. It forces your car’s suspension to negotiate with the state. Once you accept that a mound of asphalt has agency, you must ask a terrifying question: what happens when that agency is applied to the global nervous system?

The Geopolitics of the Sea Floor

When we apply Latour’s lens to the internet, the map of the world changes instantly. We stop seeing nations defined by treaties and start seeing territories defined by connection. The fiber optic cable is not merely a pipe; it is a geopolitical agent.

We are conditioned to think the internet is a decentralized mesh that can survive a nuclear war. In reality, the global economy is squeezed through a handful of glass tubes no thicker than a garden hose, resting on the bottom of the ocean.

These cables do not just carry data; they enforce a specific version of reality. Because they are physical objects, they must follow physical geography, and that geography is rarely neutral.

The Imperial Hangover: Most of the world’s data flows through routes established by the British Empire for telegraphy in the nineteenth century. The glass strands on the bottom of the Red Sea are essentially fossilized Victorian trade routes.

Digital Sovereignty: If you send an email from Brazil to Angola, logic dictates it should travel directly across the South Atlantic. But for years, the cables didn’t exist. The data had to travel north to Miami, bounce through the US infrastructure, and then cross to Europe before going south to Africa.

This is not just a detour; it is a surrender of rights. The fiber optic cable is not merely a pipe; it is a geopolitical agent with more leverage than most prime ministers. The moment that Brazilian data enters US territory—which it must, because the object demands it—it becomes subject to American surveillance laws. The cable has decided your citizenship for you.

When the Object Goes on Strike

We usually only notice these “missing masses” of society when they break. We treat technology as a “black box”—we care only about the input and the output, ignoring the complex machinery inside. But when the cable snaps, the box is pried open.

In 2008, a ship dragging its anchor off the coast of Alexandria severed a major subsea cable. There was no explosion, only silence. In a split second, seventy percent of Egypt went dark. Stock markets in Cairo froze. Call centers in Bangalore went dead.

In that moment of silence, the object revealed itself as the master. The humans in the government palaces were left frantically pressing buttons that no longer worked. It proved that our political stability is not maintained by ideology, but by the continuous pulse of light through glass.

When the object goes on strike, the human institutions built on top of it crumble. We are not ruling over nature; we are negotiating with it, and right now, we are losing the negotiation because we refuse to admit that the other side of the table even exists.

Politics in Stone and Silicon

The logic of the cable does not stop at the water’s edge. Once you accept that inanimate objects are political actors, you see the invisible wires puppeting your daily life. The political bias is not written in a manifesto; it is poured into the concrete and hardcoded into the silicon.

The classic example is the bridges of Robert Moses in New York. Moses designed overpasses leading to Jones Beach that were deliberately built too low for public buses to pass underneath. He didn’t need to pass a racist law banning the poor or minorities from the beach; he simply delegated that segregation to the granite.

Today, the low bridges are made of code. We are moving into an era of Algorithmic Governance.

Consider the gig economy worker. They do not have a human boss to argue with. They have an app. The algorithm assigns routes, sets pay, and penalizes them for resting. The app is the manager, the judge, and the executioner. You cannot unionize against a piece of software that has no ears.

Technology is society made durable.

— Bruno Latour

We are building a world where authority is embedded into the environment itself. The smart lock that refuses to open because your subscription expired is the new police officer. We are living under a rule of code, and unlike laws, code is rarely up for public debate.

Techno-Feudalism

Perhaps the most disturbing shift is who owns these silent actors. Twenty years ago, the internet’s backbone was a public utility or a consortium of telecoms. Today, the largest builders of subsea cables are Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon.

We are witnessing the privatization of the ocean floor. These corporations are no longer just running apps on top of the internet; they are physically building the internet itself. They are laying private roads that only their traffic can use.

This is a return to feudalism. We are tenants in our own digital lives, renting passage through fiefdoms owned by landlords who reside in server farms thousands of miles away. If the infrastructure itself is owned by the same entity that curates your information, neutrality is impossible.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

The illusion of the virtual world is comfortable. It is pleasant to believe that we live in a democracy of ideas, floating freely in the ether. But as Latour warned us, this comfort is a cage.

To reclaim autonomy, we must become mechanics of our own reality. We must reject the user interface—which is designed to pacify us—and look at the plumbing. We need to ask where the cables are buried, who owns the data centers, and which jurisdiction controls the hardware.

Bruno Latour did not write about these objects to make us paranoid; he wrote about them to make us observant. The cable, the algorithm, and the bridge are not neutral tools. They are the frozen will of the people who built them. True sovereignty begins when you stop looking at the screen and start looking at the wires.

A brilliant autopsy. Latour showed us that politics is frozen into objects. Today, we live in a hell of those objects all pulling in different directions. The call to 'become mechanics' is noble, but it’s a call to maintain the ICU. Does the logical, terrifying, and perhaps necessary next step point not to more mechanics, but to a single, competent doctor for the entire patient?

Really interesting piece guys, thanks!