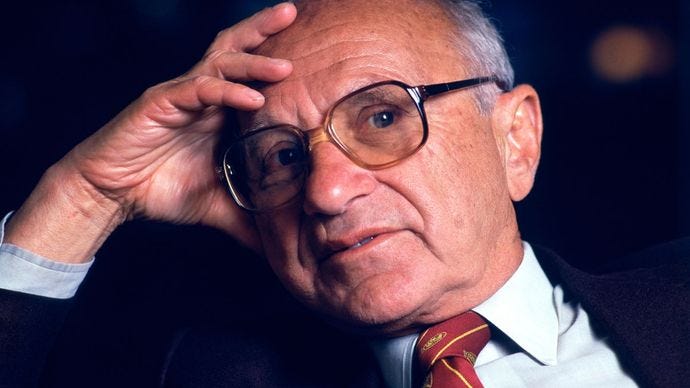

Milton Friedman: Prophet of Freedom or Architect of Inequality?

Milton Friedman remains one of the most influential and controversial economists of the 20th century. A Nobel laureate and the leading figure of the Chicago School of Economics, his name became synonymous with the advocacy of free markets, minimal government, and individual liberty. Friedman argued passionately that economic freedom was an indispensable prerequisite for political freedom. But decades after his ideas reshaped global policy, his legacy is fiercely debated: was he a prophet who liberated economies, or an architect whose blueprints fostered instability and stark inequality?

The Gospel of Free Markets and Monetarism

At the heart of Friedman's thought was a profound belief in the power of the free market, operating with minimal government interference – a philosophy often termed laissez-faire. He championed policies like deregulation, privatization, low taxation, and free trade. Central to his macroeconomic contribution was the theory of monetarism, which posited that the primary driver of economic activity and inflation was the growth rate of the money supply. This directly challenged the prevailing Keynesian orthodoxy, which emphasized government spending and fiscal policy to manage economic cycles. Friedman argued that such interventions were often ineffective or counterproductive.

There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.

This perspective, famously articulated in his 1970 New York Times Magazine article, underscored his belief that the pursuit of profit within a free market system ultimately benefited society more than explicit attempts by corporations to address social ills.

Freedom's Foundation or Faustian Bargain? The Chilean Experiment

Perhaps the most contentious application of Friedman's ideas occurred in Chile during the 1970s and 80s. Following the military coup led by Augusto Pinochet, a group of Chilean economists, many trained at the University of Chicago (dubbed the "Chicago Boys"), were given unprecedented power to reshape the economy. They implemented radical free-market reforms, including drastic deregulation, privatization, and cuts to social spending – a form of economic shock therapy. While proponents point to Chile's subsequent economic growth as evidence of the policies' success, critics highlight the immense social cost, rising inequality, and the brutal authoritarian context in which these policies were imposed. This experiment raised profound ethical questions about the relationship between economic liberalism and political repression.

Deregulation, Crises, and Consequences

Friedman's advocacy for deregulation gained significant traction in the United States and the United Kingdom from the late 1970s onwards. Policies reflecting Chicago School thinking led to the loosening of controls across various sectors, most notably finance. Critics argue that this wave of deregulation contributed significantly to subsequent financial instability. The Savings and Loan crisis of the 1980s and, more devastatingly, the 2008 global financial crisis are often cited as examples where reduced oversight allowed excessive risk-taking and systemic fragility to build. While direct causality is debated, the correlation between the era of deregulation and major financial meltdowns is undeniable, casting a shadow over the promised benefits of unfettered markets.

The Shadow of Inequality

The period coinciding with the ascendancy of Friedmanite economic policies also witnessed a dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in many Western nations. Critics contend that this was not mere coincidence. They argue that policies favoring capital over labor (such as weakened unions), tax cuts primarily benefiting the wealthy, deregulation allowing for greater financial speculation, and reduced social safety nets directly contributed to this widening gap. Friedman himself argued that while capitalism might lead to unequal outcomes, it ultimately provided more opportunity and prosperity for all compared to alternative systems. However, the scale of the inequality surge led many to question whether the version of capitalism promoted actively undermined shared prosperity.

An Enduring Legacy

Despite the critiques and the fallout from financial crises, the core tenets championed by Milton Friedman retain significant influence. Ideas about market efficiency, the dangers of government intervention, and the primacy of shareholder value continue to shape policy debates and corporate behavior. Some commentators refer to the persistence of these ideas, even when evidence seems to contradict them, as a form of "zombie economics." The fundamental assumptions about human motivation, market function, and the role of government that Friedman promoted are still deeply embedded in contemporary discourse. The ongoing relevance and impact of these economic philosophies remain a subject of intense discussion, as explored in various analyses and debates available online, such as this examination of the Chicago School's legacy:

Ultimately, assessing Milton Friedman's legacy requires grappling with profound contradictions. Was his vision of economic freedom a necessary condition for human flourishing and political liberty, lifting millions from poverty through market dynamism? Or did his emphasis on deregulation and market fundamentalism inadvertently pave the way for recurrent crises, environmental neglect, and levels of inequality that strain the social fabric? The answer remains complex, contested, and deeply relevant to the challenges we face today.

Together with Ludwig von Mises and others, the latter, an architect of inequality.

Architect of inequality obvs trickle down trick used to destroy trade unions for whom free labour markets had to be fought for and inevitably lost for socialist elected and unelected governments and competition became monopoly takeover