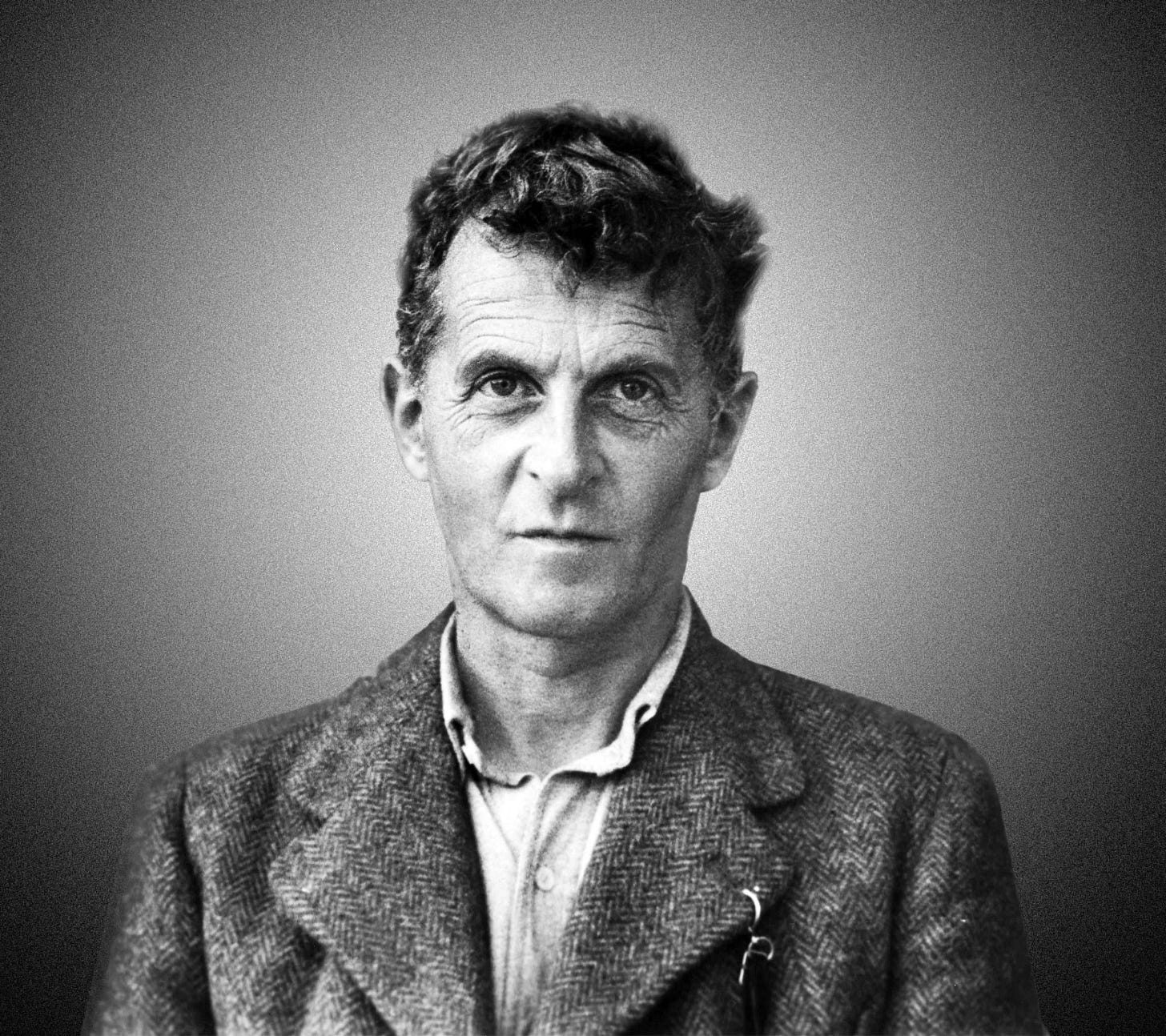

Ludwig Wittgenstein: Language Games, Pseudo-Problems, & The Crisis of Meaning

Imagine, for a moment, a philosopher who, having penned what he believed to be the definitive solution to all philosophical problems, promptly abandoned the field. He went on to teach schoolchildren, work as a hospital porter, and even design an austere house for his sister.

This wasn’t a retreat into obscurity, but a profound self-reckoning. He returned to philosophy years later, not to build upon his earlier work, but to dismantle its very foundations, revealing an entirely new landscape of thought. This was Ludwig Wittgenstein, a man whose intellectual journey mirrored the turbulent 20th century itself, transforming our understanding of language, meaning, and the very nature of philosophical inquiry.

You’ve likely felt it: that nagging sense of linguistic confusion, the feeling that debates swirl around words rather than substance, or the existential dread that meaning itself is elusive. Wittgenstein wrestled with these demons, not by offering grand theories, but by showing us how we’ve been trapped by our own linguistic habits.

The Philosopher’s Silence and the “Tractatus”’s Shadow

In his early masterpiece, “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus,” Wittgenstein sought to establish the precise limits of language. His goal was to map the logical structure of thought and reality, presenting language as a mirror, a “picture” of the world. “What can be said at all can be said clearly,” he declared, concluding that anything beyond these clear, factual statements belonged to the realm of the unsayable, the mystical. He believed he had, quite literally, solved philosophy.

Having drawn these firm boundaries, what was left for a philosopher to do? For Wittgenstein, the answer was silence. For nearly a decade, he stepped away, convinced that the problems of philosophy were largely pseudo-problems born from linguistic misunderstanding. But the silence didn’t last. A seed of doubt, a gnawing intuition that his earlier work was too rigid, too simplistic, began to sprout.

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus”

Beyond the Mirror: Language as a Tool, Not a Picture

Upon his return to Cambridge, Wittgenstein underwent a radical intellectual transformation. He began to see his earlier “picture theory” of language as fundamentally flawed. Language wasn’t a pristine mirror reflecting reality; it was a toolbox, a bustling marketplace of diverse instruments, each with its own specific function. The meaning of a word, he now argued, wasn’t found in its correlation to an object or a fact, but in its “use.”

Think about a hammer. Its meaning isn’t just its physical form, but what you “do” with it—pound nails, build, demolish. Language, he realized, functioned similarly. We don’t just speak; we promise, we question, we command, we joke, we confess, we pray. Each of these is a distinct activity, an interaction, a “game.”

The Game of Meaning: Wittgenstein’s “Language Games”

This realization led to his revolutionary concept of “language games.” For Wittgenstein, language isn’t a monolithic, logical system but a collection of diverse, context-dependent “games.” Each game has its own rules, understood by its players, and embedded within a broader “form of life”—the shared practices, customs, and activities of a community.

Consider the word “pain.” Its meaning isn’t derived from pointing to a sensation in isolation, but from the complex “game” we play around it: wincing, describing symptoms, seeking comfort, medical diagnosis. These are all parts of the social practice that gives “pain” its meaning. To understand a word, you must understand the game in which it is used.

Meaning as Use: The meaning of a word is not an object it refers to, but its role in the “game” of communication.

Context is King: Understanding comes from the specific situation and shared practices where language is employed.

“Forms of Life”: Language games are interwoven with our shared human activities, customs, and ways of living.

The meaning of a word is its use in the language.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Philosophical Investigations”

Dissolving the Fog: Pseudo-Problems and Philosophical Therapy

If meaning is rooted in use within specific language games, then many of philosophy’s oldest and most intractable problems begin to look suspiciously like category errors. They aren’t deep metaphysical riddles, but symptoms of “language gone on holiday.”

Wittgenstein famously described his philosophical method as “therapy,” aimed at showing the “fly the way out of the fly-bottle.” We get trapped when we apply the rules of one language game to another where they don’t belong. For instance, asking “What color is the number seven?” attempts to use a visual property from the “color-naming game” within the entirely different “number-counting game.” The question isn’t difficult to answer; it’s simply nonsensical within that context.

He wasn’t trying to “solve” these problems, but to “dissolve” them, demonstrating that they vanish once we properly understand the workings of our language. The role of philosophy, then, is not to build new theories, but to clarify, to untangle the knots our language creates, and to remind us of the ordinary uses we’ve strayed from.

The Crisis of Meaning in the Modern World

Wittgenstein’s insights are startlingly relevant in our contemporary world, where a pervasive “crisis of meaning” seems to loom large. When shared “forms of life” fracture, when communities become atomized, and when language is weaponized, the very ground of meaning can feel unstable.

Consider the cacophony of online discourse. Terms like “truth,” “freedom,” or “justice” are flung about, often without a shared understanding of the underlying “language game.” Different groups operate with entirely different rules for what counts as evidence, argument, or even a valid statement. This leads to a breakdown of communication, not because of a lack of facts, but because we’re playing different games with the same words.

Wittgenstein teaches us that the crisis isn’t necessarily a failure of reality to provide meaning, but a failure to appreciate the diverse, context-bound ways in which meaning is generated and sustained through our collective practices. If you’re interested in how such linguistic misdirection can be weaponized in the public sphere, consider exploring works like this deeper dive: The Invisible War for Your Mind.

Our profoundest philosophical confusions often stem not from a lack of answers, but from asking questions that language was never designed to answer in the first place.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

Ludwig Wittgenstein didn’t offer grand solutions to the universe’s mysteries. Instead, he gave us a profound method: look, don’t think. Look at how language is actually used. He invited us to step out of the abstract philosophical fly-bottle and back into the concrete reality of our everyday linguistic practices. His legacy is an enduring challenge to intellectual hubris, a call for humility in the face of language’s immense complexity, and a powerful tool for navigating the often bewildering landscape of human meaning. The journey from the “Tractatus” to the “Philosophical Investigations” is not just the story of one philosopher’s intellectual evolution, but a mirror reflecting our ongoing struggle to understand ourselves and the world through the very words we speak.

I’ve always been fascinated by Wittgenstein’s Picture Theory. For me, it’s not just philosophy. It’s a tool I use every time I write. Whether I’m breaking down a court case or digging into questions of international law, I find that this theory helps me turn abstract arguments into something clear, almost like holding up a picture for the reader. In my latest posts, I share how I use Wittgenstein’s logic to make legal analysis clearer and more engaging.

The therapeutic metaphor cuts deeper than usually noticed. Wittgenstein said the philosopher shows the fly the way out of the fly-bottle. But what happens when the bottle itself keeps changing shape?

Borges imagined a Library containing every possible book. The horror wasn't the absence of meaning but the presence of all possible meanings simultaneously. No shared game to distinguish signal from noise. The digital information environment creates something similar: an explosion of language games that no single community can encompass.

Wittgenstein grounded meaning in "forms of life," the shared practices of a community. But what happens when those forms of life fracture faster than language can adapt? We're not just playing different games with the same words anymore. We're generating new games faster than we can learn the rules, then arguing about whether the old rules still apply.

The crisis of meaning you describe isn't just about misapplication of categories. It's temporal. The rhythm of language game formation has accelerated beyond what traditional forms of life can absorb. Therapy works when there's a shared sense of health to return to. What if the fly-bottle is now an infinite regress of bottles?