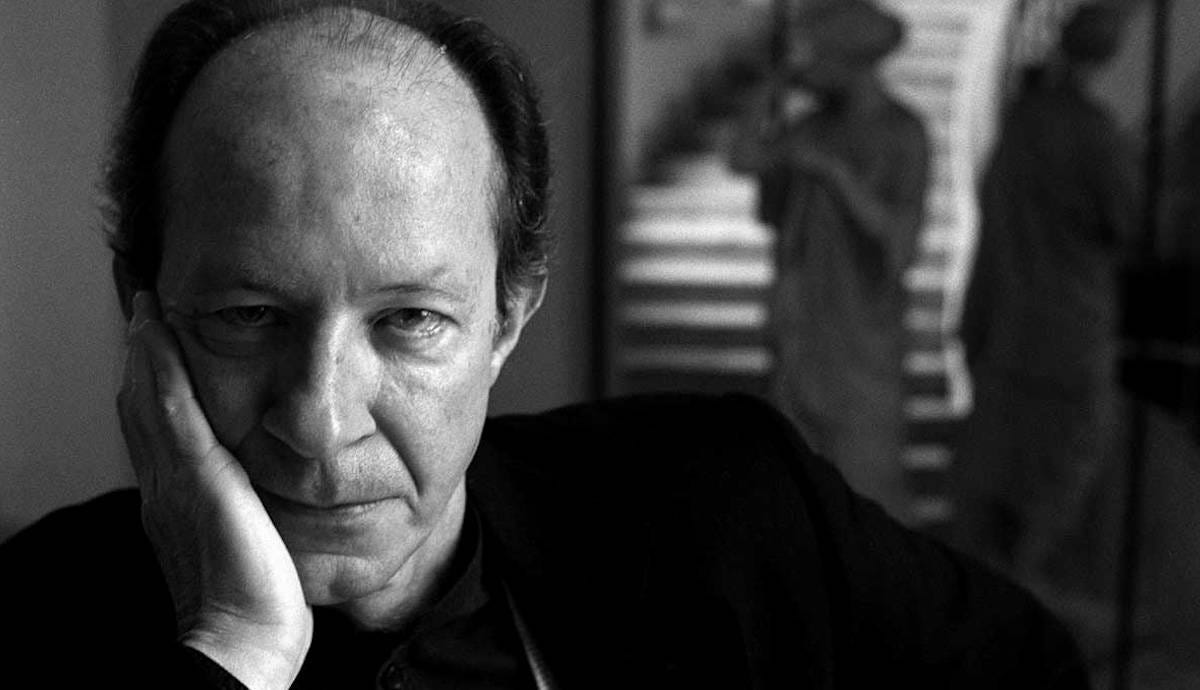

Is the "State of Exception" the New Normal? Giorgio Agamben

Introduction: The Erosion of Normality

The question of whether the "state of exception," as theorized by Carl Schmitt and later elaborated by Giorgio Agamben, has become the new normal is one of the most pressing and unsettling inquiries in contemporary political thought. Agamben, building upon Schmitt’s work, argues that the state of exception, traditionally conceived as a temporary suspension of law in times of crisis, has become increasingly normalized, blurring the lines between legality and illegality, normalcy and emergency.

This normalization has profound implications for individual rights, democratic processes, and the very nature of sovereignty. This essay will delve into Agamben's analysis, exploring the historical trajectory of the state of exception, its mechanisms, and its consequences, ultimately asking whether we are indeed living in a perpetual state of emergency.

Carl Schmitt and the Decisionist Foundation

To understand Agamben's perspective, we must first consider the foundations laid by Carl Schmitt. In his seminal work, Political Theology, Schmitt argues that "sovereign is he who decides on the exception." This seemingly simple statement reveals a radical conception of sovereignty, not as adherence to law, but as the power to suspend it. The exception, for Schmitt, is not merely an anomaly but a crucial element that defines the very essence of political authority. It is in the moment of crisis, when the normal order is threatened, that the sovereign demonstrates their power by making a decision that transcends legal norms. This "decisionist" view of sovereignty emphasizes the arbitrary and ultimately violent nature of political power.

Agamben's Bio-Politics and the Camp

Agamben expands upon Schmitt's framework in his groundbreaking work, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. He argues that the state of exception operates through a biopolitical logic, targeting "bare life"—that is, human life stripped of all political and legal protections. This is the life that can be killed with impunity, existing outside the realm of law. Agamben famously connects the state of exception to the figure of the "homo sacer" in Roman law, an outlaw who could be killed but not sacrificed, existing in a liminal space between law and nature.

The central metaphor for Agamben's argument is the "camp." The camp, whether a concentration camp, a refugee camp, or even a detention center, is a space where the state of exception is materialized and made visible. It is a zone of indistinction where the normal legal order is suspended, and where bare life is exposed to the unchecked power of the sovereign. In the camp, individuals are reduced to their biological existence, deprived of their political rights and subjected to arbitrary violence. Agamben argues that the camp is not an anomaly but a "hidden paradigm of the political," a manifestation of the inherent violence at the heart of sovereign power.

The Normalization of the Exception

Agamben's most alarming claim is that the state of exception is no longer a temporary measure reserved for extraordinary circumstances, but has become a permanent feature of contemporary governance. He points to the increasing use of emergency powers, anti-terrorism legislation, and security measures as evidence of this normalization. The events of 9/11, in particular, provided a pretext for governments around the world to expand their surveillance capabilities, restrict civil liberties, and engage in military interventions without proper legal oversight.

"The state of exception is not a dictatorship, but a space of indistinction between democracy and absolutism." - Giorgio Agamben

This normalization of the exception has several disturbing consequences. First, it erodes the rule of law and undermines democratic accountability. When governments routinely operate outside the normal legal framework, they become less constrained by legal norms and more prone to abuse of power. Second, it normalizes the biopolitical control of populations. By classifying certain groups as "enemies of the state" or "threats to national security," governments can justify their surveillance, detention, and even elimination. Third, it creates a climate of fear and insecurity, in which individuals are willing to sacrifice their freedom and rights in exchange for perceived security.

The increasing precarity of labor, the constant surveillance of digital life, and the militarization of everyday life all contribute to a sense that we are living in a permanent state of emergency. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated this trend, with governments around the world imposing lockdowns, curfews, and other restrictions on personal freedom in the name of public health. While these measures may have been necessary to contain the virus, they also demonstrated the ease with which governments can suspend normal legal procedures and exercise extraordinary powers.

Here's a relevant discussion on this topic:

Examples in Contemporary Politics

Numerous contemporary examples illustrate the normalization of the state of exception. The use of drones for targeted killings, the indefinite detention of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, and the mass surveillance programs revealed by Edward Snowden are all instances where governments have bypassed normal legal procedures and asserted extraordinary powers in the name of national security. The rise of populist and authoritarian leaders around the world, who often appeal to a sense of crisis and emergency to justify their policies, is another troubling sign.

Furthermore, the increasing militarization of police forces and the use of military tactics in domestic law enforcement create a blurring of the lines between war and peace, internal security and external defense. This militarization further normalizes the state of exception, as police officers are increasingly authorized to use lethal force and exercise quasi-military powers against civilian populations.

Resistance and the Future of Politics

If Agamben's analysis is correct, then the question becomes: how can we resist the normalization of the state of exception and reclaim our freedom and rights? Agamben himself does not offer a clear solution, but he suggests that we must develop a new understanding of politics that transcends the traditional concepts of sovereignty and law. He calls for a "coming community" that is based on a shared humanity rather than a shared identity or territory. This community would be characterized by a radical openness and inclusivity, embracing those who have been excluded and marginalized by the sovereign power.

Furthermore, a critical awareness of the mechanisms of the state of exception is crucial. We must be vigilant in defending our civil liberties, holding our governments accountable, and resisting the temptation to sacrifice our freedom in exchange for perceived security. We must also challenge the biopolitical logic that underlies the state of exception, recognizing the inherent dignity and worth of all human beings, regardless of their social status or political affiliation.

Conclusion: A Call to Vigilance

Agamben's work on the state of exception is a powerful and disturbing diagnosis of the contemporary political condition. While the claim that the state of exception has become the new normal is a provocative one, the evidence suggests that it is a trend that we cannot afford to ignore. The erosion of legal norms, the normalization of biopolitical control, and the climate of fear and insecurity all pose a serious threat to our freedom and democracy. To combat this trend, we must cultivate a critical awareness of the mechanisms of power, defend our civil liberties, and strive for a new form of politics that is based on a shared humanity and a commitment to justice. Are we prepared to confront the uncomfortable truth that the very foundations of our political order may be crumbling beneath our feet, and to actively resist the forces that seek to normalize the exceptional?

Can government be trusted with supreme power? Can anyone? No real solution