Herbert Simon & Bounded Rationality: Why Complex Systems Always Fail (A Little)

Imagine you’re designing a perfect city. Every traffic light synchronized, every bus route optimized for peak efficiency, every public service flawlessly delivered. Or perhaps you’re planning your life, meticulously mapping out the ideal career path, the perfect partner, the ultimate retirement fund. You gather data, analyze options, and strive for the absolute best possible outcome. Doesn’t it sound appealing? The dream of perfect rationality, perfect control.

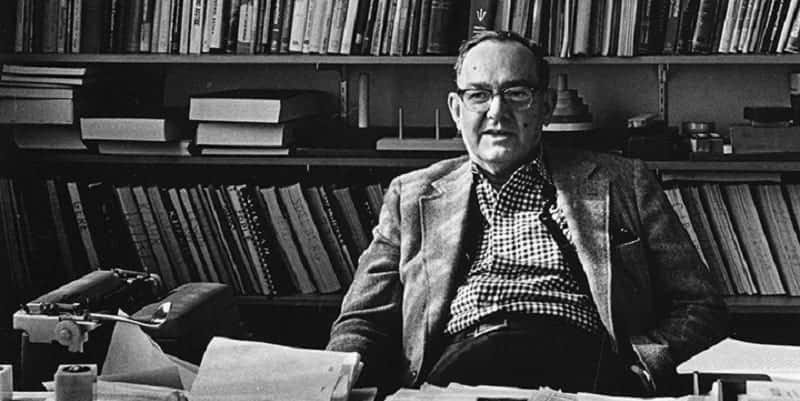

Now, look around. Do cities ever run perfectly? Do our lives ever unfold exactly as planned, without a single hitch, an unforeseen detour, or a nagging imperfection? Of course not. Traffic jams appear out of nowhere. Projects run late. Relationships hit bumps. And the "perfect" plan often ends up, well, just "good enough." What if this constant slight misalignment, this pervasive "failure (a little)," isn't a sign of our incompetence or a flaw in the system, but an inherent, inescapable feature of how we — and the complex systems we build — operate? This profound insight is at the heart of Herbert Simon’s groundbreaking concept of bounded rationality, a notion that reshaped economics, cognitive science, and our understanding of human and organizational behavior.

The Mirage of Omni-Rationality

For centuries, much of Western thought, particularly in economics, was built upon the bedrock of the "rational man" (or "Homo Economicus"). This idealized agent was assumed to possess several almost god-like qualities:

Omniscience: Access to all relevant information about all possible alternatives.

Infinite Cognitive Power: The ability to process this vast information, calculate probabilities, and predict outcomes perfectly.

Clear, Stable Preferences: Knowing exactly what they want and consistently pursuing it to maximize utility.

This perfectly rational being would always choose the absolute best option, optimizing every decision to its fullest potential. From financial markets to policy-making, the assumption was that individuals and, by extension, systems, would naturally gravitate towards optimal solutions. But does this sound like anyone you know? Or any organization you’ve worked with? Simon knew it didn't.

Simon's Revelation: Bounded Rationality

Herbert Simon, a polymath spanning political science, economics, and computer science, dared to challenge this foundational myth. He argued that the "rational man" was precisely that: a myth. In the real world, human decision-making is fundamentally constrained, or "bounded." Bounded rationality, simply put, is the idea that when individuals make decisions, their rationality is limited by:

Available Information: We never have all the data. Information is costly to acquire and often incomplete.

Cognitive Capacity: Our brains have finite memory, attention spans, and processing power. We can’t analyze every variable or foresee every consequence.

Time Constraints: Decisions often need to be made quickly, under pressure, without the luxury of endless deliberation.

Given these limitations, Simon proposed that humans don't "maximize" (find the absolute best solution) but rather "satisfice" (find a solution that is "good enough" or satisfactory). We set an aspiration level, search until we find an option that meets it, and then stop. This isn't settling; it's smart adaptation to our inherent limits. If you want a quick visual explanation of this concept, this video provides a good overview:

The capacity of the human mind for formulating and solving complex problems is very small compared with the size of the problems whose solution is required for objectively rational behavior in the real world—or even for a reasonable approximation to such objective rationality.

— Herbert A. Simon

This insight wasn't just about individual psychology; it had profound implications for understanding how complex systems function.

The Echo in Complex Systems

If individuals are boundedly rational, what happens when millions of these individuals interact within vast, intricate systems? What about organizations, governments, global markets, or even AI algorithms designed by humans? The answer, Simon implied, is that these systems inherit and amplify the "boundedness." Complex systems, by their very nature, are characterized by:

Interdependencies: Countless elements influencing each other in unpredictable ways.

Emergence: System-wide behaviors that cannot be predicted from the properties of individual parts.

Dynamic Environments: Constant change, new information, and evolving challenges.

Within such environments, the illusion of perfect control or optimal outcomes quickly dissipates. Every decision made within these systems—from designing a new software feature to implementing a national healthcare policy—is made with incomplete information, limited foresight, and constrained processing. This doesn't mean these systems catastrophically fail, but they almost *always* "fail (a little)."

The Imperfect Dance of Design and Reality

The consequences of bounded rationality ripple through every layer of complex system design and operation. Consider:

Software Glitches: Even with rigorous testing and brilliant engineers, software almost always launches with bugs. Why? Because the designers couldn't foresee every user interaction, every edge case, or every hardware conflict. They satisficed.

Policy Drift: Government policies, no matter how well-intentioned, often produce unintended consequences. The architects of the policy, operating with limited information and cognitive capacity, couldn't perfectly model the system's reaction. Adjustments, sometimes decades later, become inevitable.

Organizational Inefficiency: Companies strive for efficiency, yet internal politics, communication breakdowns, and sub-optimal resource allocation are commonplace. Departments optimize for their own goals, not always the global optimum for the entire organization.

Infrastructure Breakdown: Bridges designed for a certain load or lifespan eventually require repair or replacement, not necessarily due to poor engineering, but because the real-world conditions (weather, traffic volume, material degradation) evolve in ways impossible to predict perfectly years in advance.

These aren't signs of outright failure, but rather the constant, low-level friction and sub-optimality that emerge when boundedly rational agents interact within an infinitely complex reality. It's the hum of the imperfect machine, always needing a tweak, a patch, an update.

What behavior is rational depends on the goals, the information, and the processing power available to the actor.

— Herbert A. Simon

And for complex systems, those three elements—goals, information, processing power—are never fully aligned or perfectly available.

Embracing the "Good Enough"

Simon’s concept of bounded rationality isn't a pessimistic outlook; it's a realistic and incredibly liberating one. If perfect optimization is an impossible dream, then striving for it can be counterproductive, leading to paralysis by analysis or disillusionment. Instead, understanding bounded rationality encourages us to:

Design for Resilience, Not Perfection: Acknowledge that systems will "fail (a little)" and build in mechanisms for adaptation, learning, and recovery.

Prioritize Learning and Feedback: Since initial decisions are imperfect, continuous monitoring and feedback loops are crucial for adjustment.

Embrace Iteration: Don't expect to get it right the first time. Plan for multiple rounds of improvement and refinement.

Foster Decentralization: Allow sub-systems to satisfice locally, rather than trying to centrally optimize a system too vast for any single entity to comprehend fully.

It shifts our focus from eradicating all imperfections to managing them effectively, recognizing that the "good enough" is often the most sensible and achievable path forward.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

Herbert Simon's concept of bounded rationality offers a profound lens through which to view the world. It explains why our personal resolutions often falter, why businesses constantly restructure, and why even the most advanced technological systems require endless updates. It’s not a lament about human inadequacy, but a powerful recognition of our fundamental nature and the inherent complexity of the world we inhabit. The next time you encounter a minor glitch, a slight delay, or a plan that didn't quite hit its mark, remember Simon. It's not necessarily a sign of a broken system, but rather the subtle, persistent echo of bounded rationality. Complex systems, by their very design and the nature of their creators, will always "fail (a little)." The true wisdom lies not in denying this reality, but in understanding it, adapting to it, and designing systems that thrive despite—or perhaps because of—this beautiful, unavoidable imperfection. What does this realization mean for how you approach your next big decision?

Was just reading today in Barrett of the ‘unbounded rationalism’ of the medieval thinkers!

I enjoyed reading your post today. In my experience, the more complex the system, the more opportunity for failure. If you cannot leverage your failures for growth, they only distract.