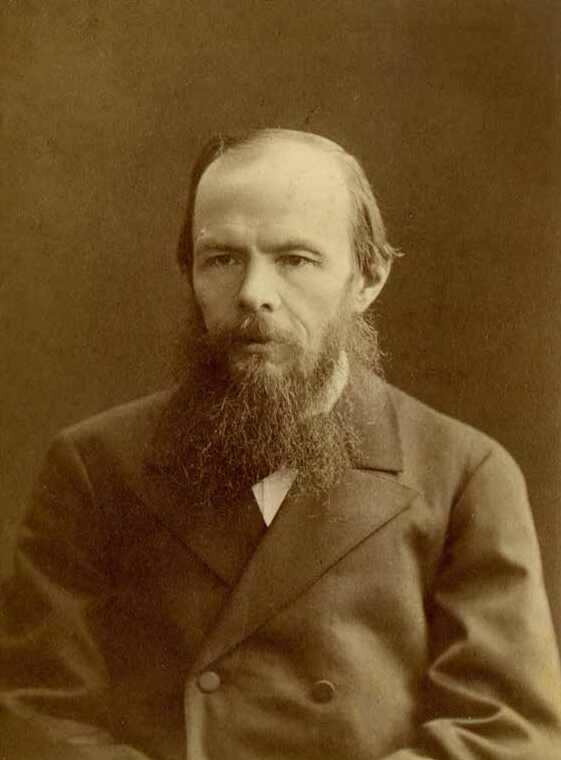

Fyodor Dostoevsky's Grand Inquisitor: The Chilling Prophecy of Why We Choose Chains

Imagine a bustling, sun-drenched square in 16th-century Seville. The air is thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of a devout crowd. Suddenly, a figure appears, radiant and benevolent, performing miracles that echo ancient texts. It is Jesus Christ, returned to Earth. But his joyous reunion with humanity is short-lived. He is arrested, interrogated, and condemned, not by an angry mob, but by the most powerful figure of the Church: the Grand Inquisitor.

This is the electrifying premise of "The Grand Inquisitor," a "poem" recounted by Ivan Karamazov to his brother Alyosha in Fyodor Dostoevsky's monumental novel, "The Brothers Karamazov." It is more than just a fictional encounter; it is a profound philosophical dissection of human nature, freedom, and the terrifying allure of authority.

Dostoevsky, with his unparalleled insight into the human psyche, crafted a narrative that, nearly 150 years later, still resonates with unsettling prescience. Are we truly creatures who yearn for absolute freedom, or do we, deep down, prefer the comfort of chains?

The Paradox of Freedom and Burden

The Grand Inquisitor's argument is simple, yet devastating: Christ made a fundamental error. He offered humanity ultimate freedom—the freedom to choose between good and evil, to believe or not believe, to forge one's own path to salvation. But, according to the Inquisitor, this freedom is not a gift; it is an unbearable burden.

He contends that ordinary people are too weak, too fallible, to bear the weight of such choice. They crave security, certainty, and someone to tell them what to do. Is he wrong? Look around. In times of crisis, do we not often flock to strong leaders, seeking clear answers, even if it means surrendering a degree of our autonomy?

The Inquisitor believes humanity is inherently afraid of true freedom, seeing it as a source of agony, confusion, and despair. He argues that by relieving people of this terrible freedom, by providing them with material sustenance, unquestionable authority, and a clear moral code, he offers them happiness, even if it's an illusion.

For nothing has ever been more insupportable for a man and a human society than freedom.

— The Grand Inquisitor

The Three Temptations Revisited

The Inquisitor cleverly reframes Christ's three temptations in the wilderness to bolster his argument:

Bread: Christ refused to turn stones into bread, insisting that "man shall not live by bread alone." The Inquisitor argues this was a mistake. People crave material security above all else. Provide them with bread, and they will follow you, eagerly surrendering their freedom.

Miracle/Mystery: Christ refused to jump from the temple, refusing to force belief through a spectacular miracle. The Inquisitor believes humanity needs miracles and mystery. They need something tangible to believe in, not the silent call to faith. They will follow those who promise wonders, not those who demand radical, personal conviction.

Authority/Power: Christ refused to accept all the kingdoms of the world from Satan, choosing spiritual leadership over earthly dominion. The Inquisitor asserts that people yearn for someone to unite them, to take the burden of choice off their shoulders. They want a single, supreme authority to dictate their lives, ensuring order and happiness.

In the Inquisitor's view, he and the Church have corrected Christ's "mistakes." They have taken up the cross of providing earthly bread, spectacular mystery, and unifying authority, all to ensure humanity's collective happiness and peace.

The Benevolent Dictator's Logic

What makes the Grand Inquisitor so chilling is that he is not presented as purely evil. He genuinely believes he is acting out of love for humanity, sacrificing his own soul for their "happiness." He confesses that he and his ilk are doomed to suffer in secret, bearing the terrible truth of their deception, all for the sake of the "flock."

His logic is deeply unsettling:

The Illusion of Choice: He promises a world where people can "sin" without guilt, as long as they confess and submit. They are given the illusion of choice, while their lives are meticulously managed.

Peace Through Control: He guarantees peace and order by removing the agonizing responsibility of moral decision-making. No more existential dread, just simple obedience and a full belly.

The Lie for Happiness: He concludes that the greatest kindness one can offer humanity is to lie to them, to give them a comforting illusion rather than a painful truth.

We will persuade them that they will only become free when they renounce their freedom to us and submit to us.

— The Grand Inquisitor

The Silence of Christ and Our Complicity

Throughout the Inquisitor's lengthy, impassioned monologue, Christ remains utterly silent. He offers no rebuttal, no defense. His only response is a kiss on the Inquisitor's "bloodless, aged lips." This silence is arguably the most profound aspect of the "poem."

What does it mean? It suggests that true freedom cannot be argued into existence; it must be chosen and lived. It is a radical acceptance of the burden, the risk, and the isolation that comes with genuine autonomy. Christ's silence is an invitation, not a command, to embrace the magnificent, terrifying gift of free will.

This brings us to our own complicity. Do we, in our modern lives, not often find ourselves gravitating towards the very things the Inquisitor promised? Do we:

Prioritize Convenience: Opt for algorithms that filter our news and entertainment, removing the need for critical engagement?

Seek External Validation: Base our self-worth on likes and followers, rather than intrinsic values?

Demand Simple Answers: Shun complex problems for charismatic figures who promise easy solutions to societal woes?

The Inquisitor's prophecy isn't just about a religious institution; it's about the innate human desire for comfort over conviction, for security over the unsettling vastness of true liberty.

The Chilling Prophecy in the Modern Age

Dostoevsky's 19th-century vision feels startlingly contemporary. The "invisible war for your mind" that thinkers like Noam Chomsky discuss finds a spiritual ancestor in the Inquisitor's methods. We live in an age of unprecedented information and connection, yet also an age of unprecedented manipulation and manufactured consent.

From social media echo chambers that reinforce our biases to political narratives that simplify complex realities, we are constantly presented with attractive frameworks that promise to alleviate the burden of independent thought. The allure of belonging, the comfort of having "experts" or "influencers" guide our opinions, and the sheer mental exhaustion of constant critical evaluation can lead us to willingly hand over our intellectual and moral autonomy.

For a deeper dive into how psychological manipulation operates in our daily lives, this video offers valuable insights: The Invisible War for Your Mind.

Perhaps Dostoevsky's most unsettling revelation is not that we are forced into chains, but that given the chance, we often forge and embrace them ourselves, believing we are finally free.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

"The Grand Inquisitor" remains a powerful, disturbing mirror reflecting the deepest anxieties and desires of the human spirit. It asks us to confront an uncomfortable truth: that the capacity for freedom is often overshadowed by the desire for security, certainty, and comfort. Dostoevsky's genius lies in presenting this through the chillingly benevolent logic of a man who genuinely believes he is saving humanity by enslaving it.

As we navigate an increasingly complex world, the "Poem" serves as a timeless warning. It compels us to ask: What price are we willing to pay for peace and order? Are we truly prepared to bear the magnificent, terrifying burden of our own freedom, or will we continue to seek out those who promise to take it from us, offering in return the seductive illusion of happiness within golden chains?

This certainly is chilling. It follows the same logic as the welcoming prayer in Centering Prayer. Father Thomas Keating talked about letting go of our need to control, seek approval, and the need for safety and security. These are also based on the temptations of Christ.

Funny, for years now I've been saying that only about 10% of the population is actually capable of thinking for themselves, and that the appeal of religion historically has been the Grand Inquisitor's very proposition, that it's easier to give up your mental autonomy to an "authority" than to have to think for yourself.