Effective Altruism Explained: Peter Singer's Radical Philosophy & Moral Challenge

Imagine you're walking down the street and see a child drowning in a shallow pond. You're wearing an expensive suit, which will be ruined if you jump in to save the child. Would you do it? Most of us would, without hesitation. But what if, instead of a drowning child, you could donate a sum of money and save a child's life through a charity? Would you do it then? This, in a nutshell, is the challenge posed by Effective Altruism (EA), a philosophy that's rapidly gaining traction, and sparking intense debate. It’s a movement championed by thinkers like Peter Singer, and it demands we radically rethink our moral obligations.

The Moral Compass: Why Do We Do Good?

We're all familiar with the feeling – the urge to help, to ease suffering. But why? Is it innate empathy? Social pressure? Or perhaps a desire for personal satisfaction? Whatever the reason, we generally agree that doing good is, well, good. But how far does that obligation extend? And what constitutes *effective* good?

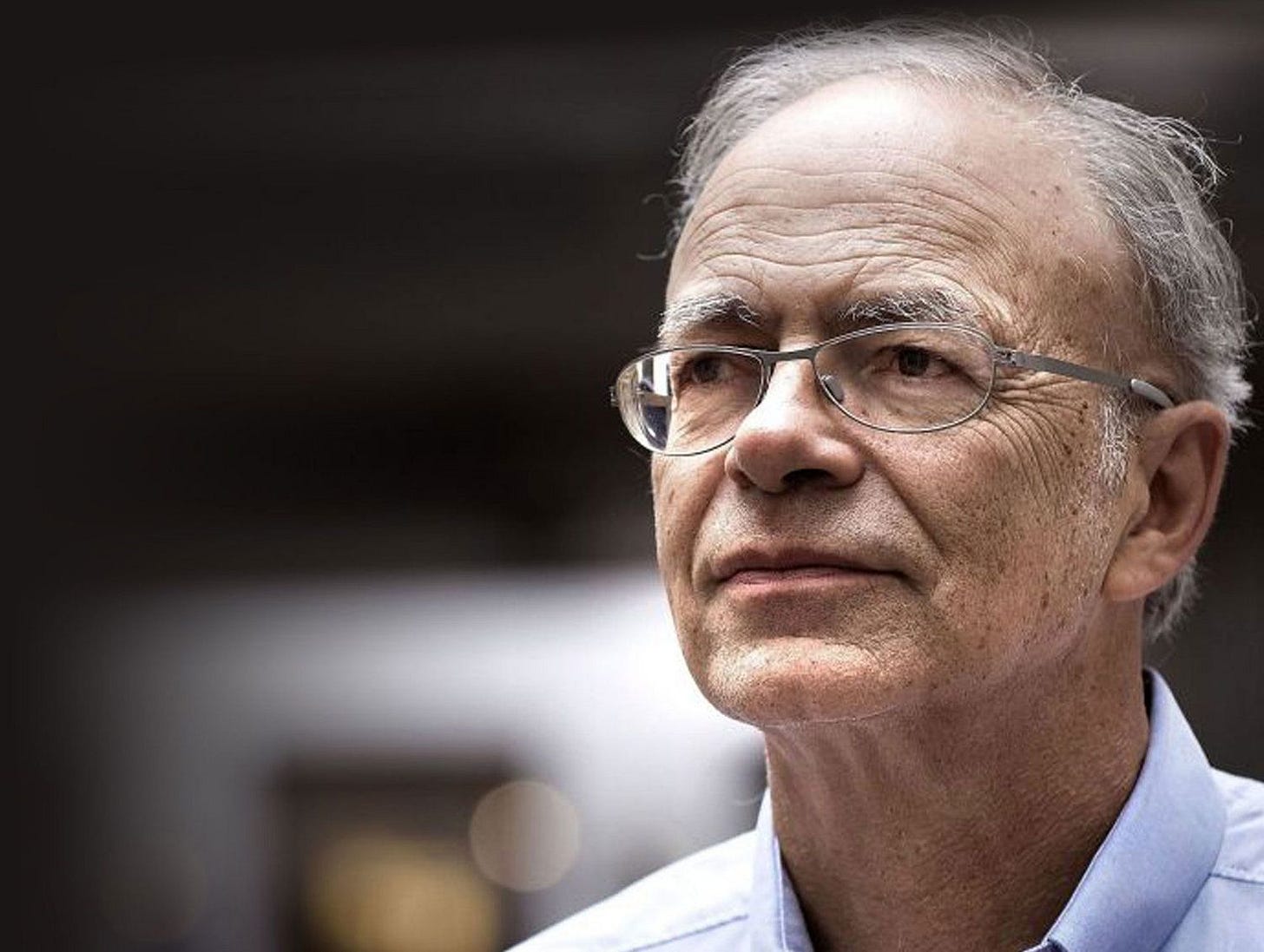

Traditional ethics often focuses on our immediate surroundings, the people we know and love. We prioritize the needs of family, friends, and community. But what about those suffering across the globe? Do we have a moral responsibility to help them as well? This is where Peter Singer, the Australian philosopher and a key figure in the Effective Altruism movement, challenges our assumptions.

Peter Singer & The Ethics of Giving

Peter Singer's work, particularly his book "The Drowning Child," provides a foundational argument for EA. His core principle is simple: if we can prevent something bad from happening without sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance, we ought, morally, to do it. Think about it. That expensive suit? It’s morally insignificant compared to a child's life. The same logic, Singer argues, applies to global poverty and suffering.

Singer is a utilitarian. He believes the best action is the one that maximizes overall well-being. This leads him to advocate for radical actions, like donating a significant portion of your income to effective charities. He isn't calling for a perfect, monastic life, but for a *significant* commitment.

“If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.” – Peter Singer, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”

Defining "Effective": The Role of Evidence

EA isn't just about giving; it's about giving *effectively*. This means using evidence and reason to determine which charities are most impactful. This involves a rigorous, data-driven approach to philanthropy, focusing on metrics and outcomes. Organizations like GiveWell provide research and recommendations on the most effective charities, often focusing on areas like mosquito nets to prevent malaria or cash transfers to families in need.

Think of it like investing. You wouldn't throw your money at a company without researching its financial performance. EA encourages a similar approach to charitable giving, urging donors to carefully evaluate the impact of their donations. This can involve:

Reviewing evidence-based research on charity effectiveness.

Considering cost-effectiveness (how much impact per dollar).

Prioritizing interventions with proven success.

The Challenges and Criticisms of Effective Altruism

While the logic of EA can be compelling, it's not without its critics. One common concern is the demanding nature of the philosophy. Is it truly realistic to expect people to donate a large portion of their income, or drastically change their lifestyles, to maximize their impact?

Another critique focuses on the potential for EA to create a sense of moral superiority, or to neglect the complexities of social justice. Critics argue that simply addressing immediate needs, like poverty, without tackling the underlying systemic issues is not a sustainable solution. Is EA a genuine force for good, or a form of virtue signaling?

And, of course, there’s the potential for unintended consequences. How do we know, with absolute certainty, that a charity is truly effective? Is the focus on measurable impact leading to neglect of other valuable, but less easily quantifiable, forms of good, such as supporting the arts or fostering community? Watch this video for further discussion of the movement and the challenges it faces:

The Personal Dilemma: Where Do We Draw the Line?

Ultimately, EA forces us to confront a deeply personal question: what are our moral obligations? It asks us to re-evaluate our priorities and our relationship with the world. How much are we willing to sacrifice to make a difference? It's a constant balancing act, between our own needs, the needs of our loved ones, and the suffering of others.

The key, perhaps, isn't about achieving perfection, but about striving for continuous improvement. It’s a process of reflection, adjustment, and a commitment to doing the most good we can with the resources we have.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

A Call to Conscience

Effective Altruism is more than just a philosophy; it’s a call to action. It challenges us to be more rational, more evidence-based, and more compassionate in our giving. It demands a constant questioning of our assumptions, a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, and a commitment to making the world a better place. It’s a radical philosophy, but one with the potential to profoundly impact how we live our lives.

So, back to that pond. Would you jump in?