Edward Herman's Filters: The Invisible War for Your Mind in the Digital Age

Have you ever scrolled through your newsfeed and felt… uneasy? Like something isn't quite right, even though all the headlines seem to check out? Perhaps you’ve wondered why certain stories get amplified, while others – stories that seem critically important – vanish into the digital ether. In today’s hyper-connected world, the flow of information is relentless, a constant stream of data vying for our attention. But what if that stream isn't as pure as it seems? What if it's been subtly, and not-so-subtly, filtered? This isn't about rogue algorithms or accidental bias; it’s about a systematic process – a framework – that shapes what we see, what we believe, and ultimately, how we understand the world. We are, whether we realize it or not, participants in an ongoing information war.

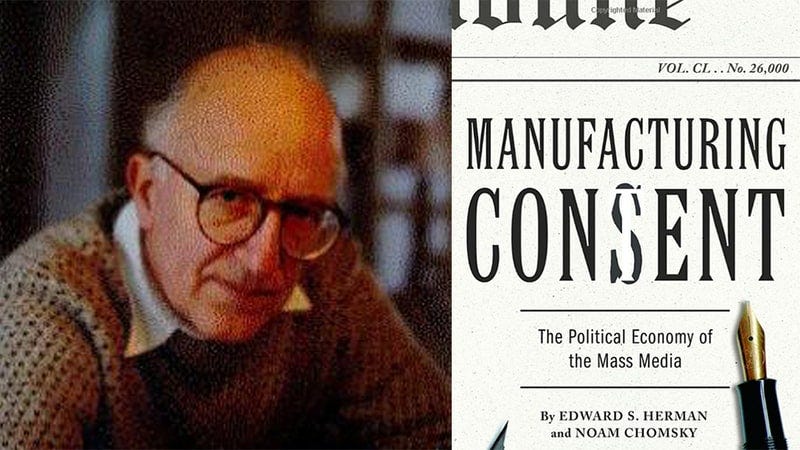

The Man Behind the Curtain: Edward S. Herman

To understand the current state of media manipulation, we need to understand where it comes from. While many have observed media bias, few have articulated a cohesive theory as influential as that of Edward S. Herman, a brilliant professor of finance at the University of Pennsylvania. Together with Noam Chomsky, Herman developed the Propaganda Model, outlined in their groundbreaking book, *Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media*. This model isn't a conspiracy theory; it's a sociological framework, a set of filters that, in Herman’s words, explain how media operates within a capitalist system. And in the digital age, with its ever-growing data and unprecedented capabilities, these filters have become even more potent.

Filter 1: Ownership and Profit

The first, and arguably most fundamental, filter is ownership. In the age of tech giants, who owns the media? The answer is a handful of immensely powerful corporations, and their primary goal is profit. Think about it: media outlets are businesses. They have shareholders, they need to generate revenue, and they are beholden to the economic imperatives of their owners. What happens when a story threatens those interests? What happens when a news report damages a major advertiser? The incentives are clear, and the pressure is often subtle but persistent.

Consider the recent acquisition of media outlets by huge corporations. These entities are not primarily interested in truth-telling or public service. Their first priority is to increase their profits and enhance the value of their stock. News is a product, and like any product, it must be tailored to the needs of its market. What happens to reporting that runs contrary to the owners' interests? It gets… adjusted. Or perhaps, it gets dropped altogether.

Filter 2: Advertising as a Primary Income Source

Advertising, the second filter, works hand-in-hand with ownership. Media outlets rely heavily on advertising revenue. This creates a dependence on advertisers, and advertisers, naturally, want to reach the largest possible audience. This leads to a focus on content that appeals to a broad demographic, content that is, shall we say, safe. Content that offends or alienates key advertisers is risky. Controversial reporting, investigative journalism that challenges powerful corporations, or stories that threaten the status quo? These can be problematic for ad revenue. Is it a coincidence that so much of mainstream media focuses on celebrity gossip, lifestyle trends, and easily digestible narratives?

The advertising model also encourages a focus on sensationalism, clickbait headlines, and emotionally charged content. Why? Because these things grab attention, and attention translates into revenue. In the digital realm, this effect is magnified by algorithms that prioritize engagement, further reinforcing these trends. The result? We are bombarded with information designed to keep us hooked, not informed.

Filter 3: The Reliance on Sourcing

The third filter focuses on sourcing. Media outlets often rely on "official sources" – government officials, corporate spokespeople, and other powerful actors. This reliance creates a systemic bias. These sources control the flow of information, and they have a vested interest in shaping the narrative. The media, in its constant pursuit of immediacy and access, becomes reliant on these sources for a steady stream of content. This leads to a narrow range of perspectives and a reluctance to challenge the established order. What happens to the voices of dissent? They are often marginalized, ignored, or dismissed as unreliable.

Consider how often the news is framed by press releases or interviews with government officials. How often are dissenting voices, alternative viewpoints, or whistleblowers given the same platform? The very structure of media production tends to favor those who already hold power. Think about the implications of this filter as it plays out in times of crisis or war. The dominant narrative is often shaped by those who have the most to gain from it.

Filter 4: Flak and the Enforcers

The fourth filter, "flak," refers to the negative responses to a media statement. It can come from public criticism, lawsuits, or lobbying from powerful individuals, groups, or corporations. Flak can be a powerful tool for suppressing dissenting voices and discouraging critical reporting. When media outlets face pressure – whether it's threats of legal action, boycotts, or public smear campaigns – they are less likely to publish stories that challenge the status quo. This creates a climate of self-censorship, where reporters are hesitant to investigate sensitive topics or criticize powerful interests.

Furthermore, flak can be used to discredit sources, attack the reputations of journalists, and undermine the credibility of independent media outlets. The goal is simple: to silence critics and protect the interests of those in power. The internet, sadly, has amplified the impact of flak. Online smear campaigns and coordinated attacks can quickly tarnish a reputation and intimidate those who dare to speak truth to power.

Filter 5: The Common Enemy

The fifth filter involves the use of common enemies. When covering domestic or foreign matters, it's often helpful to create the image of a common threat, a threat the public will rally against. This can be an external enemy, such as a foreign government or terrorist group, or an internal one, such as a political rival or social movement. By demonizing these enemies, the media can generate support for government policies, distract from domestic problems, and divert attention from the actions of those in power.

The creation of a "common enemy" is a powerful tool of social control. It can be used to justify wars, suppress dissent, and consolidate power. The media often plays a crucial role in this process, shaping public perception and manufacturing consent for actions that might otherwise be opposed. Consider how this filter works in times of political polarization, when media outlets exploit and exacerbate divisions to maintain audience loyalty.

The Digital Age and the Amplification of Bias

The digital age has profoundly transformed the media landscape, and not always for the better. While the internet offers unprecedented opportunities for information sharing and access, it has also amplified the effects of Herman's filters. The concentration of power in the hands of a few tech giants, the pervasive influence of advertising, the reliance on algorithmic curation – these forces are reshaping the flow of information in ways that are both subtle and profound. In the following video, you can find a comprehensive overview of these ideas.

The Illusion of Choice

One of the most insidious effects of these filters is the illusion of choice. We are constantly bombarded with information, but much of it is filtered, shaped, and curated to reinforce existing power structures. The algorithm is the new gatekeeper, and it knows far more about us than we realize. What we see, what we read, what we believe – it's all being shaped, often without our conscious awareness. We think we are making choices, but in reality, we are often navigating a carefully constructed echo chamber. Is this true freedom of thought? Or a sophisticated form of control?

"The propagandist’s purpose is to make one set of facts or ideas acceptable to us while blocking out another set." – Edward S. Herman

Breaking the Cycle

So, what can we do? Recognizing the existence of these filters is the first step. We must become critical consumers of information, questioning the sources, the motivations, and the narratives that we are presented with. We must support independent media, explore diverse perspectives, and actively seek out information that challenges our own beliefs. We must demand transparency from tech companies and hold them accountable for the ways in which their platforms shape our world. This, in essence, is a fight for the truth, a fight for the very future of our minds.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion: The Fight for Truth in a Filtered World

Edward Herman's Propaganda Model offers a powerful framework for understanding how media bias works. In the digital age, his filters have become even more relevant, more pervasive, and more insidious. The ownership of media outlets, the reliance on advertising, the dependence on official sources, the power of flak, and the manipulation of the "common enemy" – all of these factors contribute to a system that shapes what we see, what we believe, and how we understand the world. The key is to become aware of these processes and to resist the forces that seek to control our minds. The invisible war for your mind is real, and the battle for truth starts with you.

It seems as if You were giving more crédit to Herman than to Chomsky for this Milestone. I think that they both deserve credit equally for Manufaruring Consent.