Beyond the Lever: Philippa Foot's True Trolley Problem & The Power of Virtue Ethics

Imagine, for a moment, a runaway trolley hurtling down the tracks. Ahead, five innocent people are tied to the rails, oblivious to their impending doom. You stand beside a lever. Pulling it will divert the trolley onto a different track, where only one person is tied. What do you do? Most of us, faced with this classic "trolley problem," instinctively feel the pull of utilitarian calculus: five lives saved, one lost. A difficult choice, perhaps, but a logical one, right?

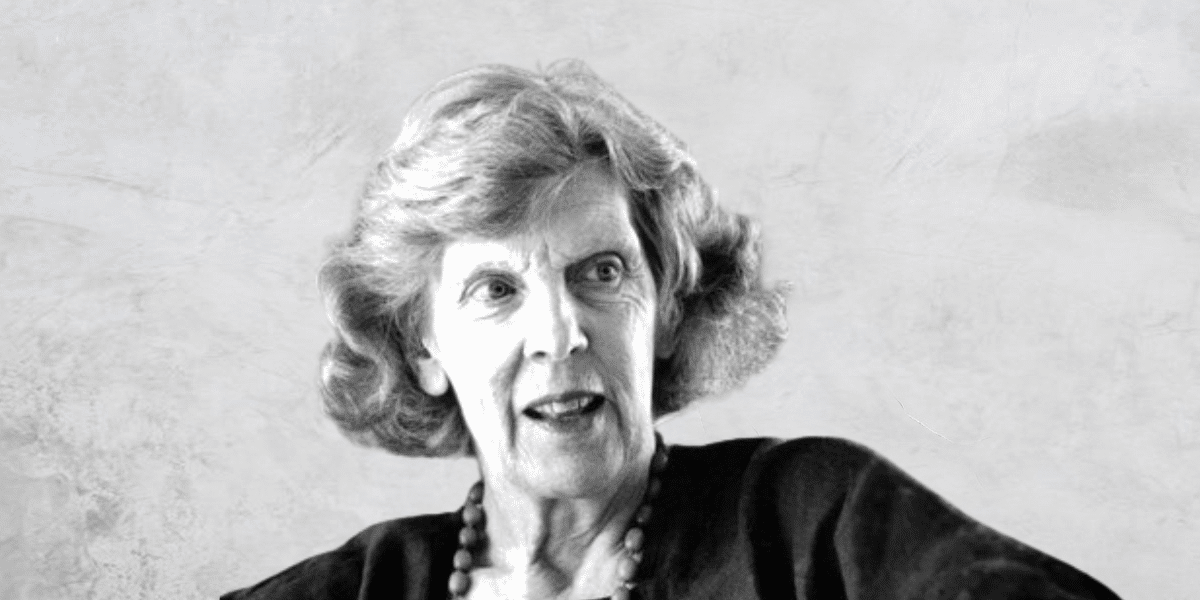

This scenario, however, is a profoundly simplified, even distorted, version of the ethical dilemma originally posed by philosopher Philippa Foot. The popular rendition, often presented in philosophy classes and pop culture alike, has obscured the far deeper and more unsettling questions Foot truly sought to explore. It has turned a nuanced inquiry into moral agency into a mere numbers game, a cold calculation of outcomes.

But what if the problem isn't just about pulling a lever? What if it's about actively, intentionally, choosing to harm one person to save others? What if the "choice" isn't about diverting an existing threat, but about *creating* a new one, a direct violation of individual rights and human dignity?

This, my friends, is "Beyond the Lever." This is where Philippa Foot's true trolley problem begins, and where the often-misunderstood power of Virtue Ethics truly shines.

The Lever, The Tracks, and The Illusion of Choice

The standard trolley problem, as most people know it, is elegant in its brutality. It presents a clear-cut choice: sacrifice one to save five. The decision feels inevitable, almost scientific. It seems to pit two ethical frameworks against each other:

Utilitarianism: Maximize overall good, save the most lives.

Deontology: Follow strict moral rules; don't directly kill, even if it saves others.

But the framing itself subtly pushes us towards one conclusion. You're not *killing* the one; you're *diverting* a threat that already exists. It feels less like an active violation and more like a grim administrative decision. This setup has become a ubiquitous thought experiment, a shorthand for understanding ethical dilemmas.

Yet, by focusing solely on this lever, we miss the forest for the track switch. We miss the very core of what Foot was grappling with.

Foot's True Trolley: A Different Kind of Agency

Philippa Foot’s original trolley problem, outlined in her 1967 essay "The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect," was not about diverting a runaway trolley. Her central concern was the distinction between killing and letting die, and the moral difference between various types of intentional harm.

Consider Foot's real scenarios:

The Judge: A judge is faced with a riot, demanding a culprit. If he frames an innocent man and condemns him to death, the mob will be appeased, and many lives will be saved. If he does nothing, the riot will escalate, leading to widespread death and destruction.

The Doctor: A doctor has five dying patients, each needing a different organ. A healthy person walks into the hospital for a routine check-up. The doctor could kill the healthy person, harvest their organs, and save the five.

Do you see the critical difference? In these cases, there is no runaway trolley. There is no existing threat being *diverted*. Instead, a new, direct, intentional act of harm is being proposed against an innocent individual. The judge is not merely allowing a threat to continue; he is *creating* a victim. The doctor is not simply choosing which patient to treat; he is *murdering* one to save others.

This is not a matter of impersonal calculation; it is a matter of profound moral agency. It forces us to confront the question: Is it ever permissible to actively commit a grave injustice against an individual, even if it leads to a greater good? For a deeper dive into this distinction, consider watching this insightful video: The Trolley Problem and Philippa Foot.

If we have duties of justice to one man we may not be able to fulfill them and also fulfill duties of charity to others. It is only if we think of a duty of charity as automatically overriding any duty of justice that we shall be in trouble.

— Philippa Foot, "The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect"

The Flaw in the Utilitarian Machine

The popular trolley problem's focus on the lever-pulling scenario inadvertently trains us to think like calculators. It asks us to weigh numbers, to prioritize consequences above all else. This purely consequentialist approach, while seemingly logical, can be deeply problematic.

When we reduce morality to a mathematical equation, we risk:

Dehumanization: Individuals become mere data points in a larger calculation, their inherent worth easily overridden by the "greater good."

Erosion of Rights: If the ends always justify the means, then fundamental rights (like the right not to be murdered) become conditional, subject to the exigencies of a situation.

Moral Blindness: We might become desensitized to the act of direct harm, provided the outcome appears beneficial on paper.

Is it always "better" to save more lives if the act of saving them involves a direct, unjustifiable violation of another's rights? What kind of society would we create if such actions were routinely sanctioned, provided the "numbers" worked out?

Virtue Ethics: Beyond the Numbers Game

Philippa Foot, along with other prominent philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre, was a key figure in the revival of Virtue Ethics. This ancient ethical framework, championed by Aristotle, shifts the focus from actions or consequences to the character of the moral agent. It asks not "What should I do?" but "What kind of person should I be?"

In the context of Foot's true trolley problem, Virtue Ethics offers a powerful alternative to the utilitarian trap. It compels us to consider the virtues that would be compromised or upheld by our actions.

Consider the virtues challenged by the "judge" or "doctor" scenarios:

Justice: Would a just person frame an innocent individual? Virtue ethics argues that justice is an indispensable virtue, not something to be sacrificed for expediency.

Integrity: Would a person of integrity directly commit an act they know to be morally reprehensible, even if the outcome is positive?

Compassion: While compassion might prompt us to save many, it also requires us to recognize the inherent worth of each individual, preventing us from treating them as mere means to an end.

Courage: Sometimes, the virtuous choice is to stand firm against an unjust act, even if it means facing difficult consequences or letting a "worse" outcome unfold.

Virtue ethics demands that we cultivate a moral character that intuitively recoils from such injustices, not because of a rigid rule, but because it is antithetical to what it means to be a truly good person.

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.

— Will Durant, summarizing Aristotle

Reclaiming Our Moral Compass

The distinction between the popular trolley problem and Foot's original scenarios is more than an academic quibble. It speaks to the heart of how we approach ethical decision-making in the real world.

We face "judge" and "doctor" dilemmas all the time:

In political policy, where the rights of a minority might be sacrificed for the perceived good of the majority.

In technological development, particularly with AI ethics, where algorithms might be designed to make "optimal" choices that bypass fundamental human rights.

In public health crises, where difficult decisions about resource allocation can inadvertently lead to justifying direct harm to some for the benefit of others.

Philippa Foot's true trolley problem forces us to look beyond simplistic cost-benefit analyses. It challenges us to ask not just "What is the outcome?" but "What does this action say about me? What kind of society are we building by making such choices?" It reminds us that morality is not just about crunching numbers; it's about character, about upholding fundamental principles, and about recognizing the inviolable dignity of every human being.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

The enduring popularity of the lever-and-tracks trolley problem has inadvertently skewed our understanding of ethical philosophy. By stripping away the direct moral agency, it has fostered a utilitarian bias that sometimes obscures the deeper, more uncomfortable truths about human responsibility.

Philippa Foot's original scenarios, however, pull us back from the brink of pure calculation. They force us to confront the profound difference between allowing harm to occur and actively perpetrating it. They reintroduce the human element, the moral agent, into the heart of the ethical dilemma.

Through the lens of Virtue Ethics, we are invited to cultivate not just a set of rules, but a robust moral character—one that prioritizes justice, integrity, and compassion, even when faced with overwhelming pressures and the promise of a "greater good." Beyond the lever, beyond the numbers, lies the true challenge: to be the kind of people who would never, under any circumstance, willingly frame an innocent person or harvest organs from a healthy one. This is the enduring power of virtue ethics, reminding us that the choices we make define not just the world, but ourselves.

Seems preposterous to me and ridiculously complicated. The average person needs religion if he's going to have any virtue or morality or ethics.

Rather than worry about a railroad car hurtling down the tracks , it's better to think of the Roman Colosseum where after 10,000 years the Christian monk Telemacus interceded and forced them to stop in the name of Jesus Christ.

Added can be: if you chose to pull the lever, reconsider your choice