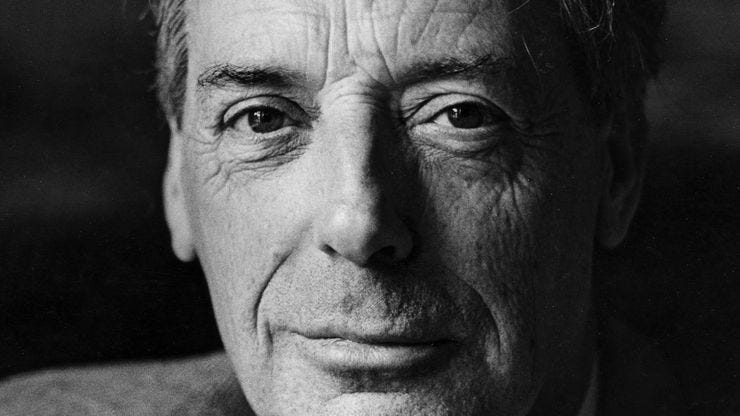

Bernard Williams: The Uncomfortable Truth About “Goodness” and Moral Life

We’re taught from an early age that being a “good person” is the ultimate aspiration. It’s the gold standard, the moral compass, the quiet promise of a life well-lived. We chase it, striving to fit into a universally approved mold, believing that ethical certainty is just a carefully followed rulebook away.

But what if this pursuit, this very idea of a singular, universally “good person,” is a dangerous illusion? What if the tidy frameworks of traditional moral philosophy fundamentally misunderstand the messy, conflicted reality of human experience?

Enter Bernard Williams. A philosopher whose sharp intellect and even sharper wit cut through the comforting facade of conventional morality, revealing the complex, often tragic, landscape beneath. Williams wasn’t interested in giving us new rules to live by; he wanted us to confront the very nature of moral life with unflinching honesty. He dared us to question whether the quest for a perfectly “good” self might actually be a profound betrayal of who we truly are.

The Allure of Universal Morality: A Scientific Dream

For centuries, philosophers have yearned for a moral system as elegant and irrefutable as mathematics or physics. They’ve sought universal principles, exceptionless laws, a grand unified theory of right and wrong that could guide every action, in every situation, for every person. It’s an understandable desire, a longing for certainty in a world brimming with ambiguity.

This aspiration, Williams argued, often reduces moral philosophy to a kind of “moral science.” It presumes that ethical problems can be solved by applying abstract rules, much like solving an equation. But is human experience truly so neat and predictable? Is morality merely a logical puzzle waiting to be universally cracked?

Moral philosophy is not a scientific enterprise that can aspire to knowledge in the way that science does.

— Bernard Williams

The Distortion of Human Experience

Williams believed that this reductionist tendency, this search for universal moral laws, profoundly distorts the rich, complex reality of human moral experience. Our lives aren’t lived in a vacuum of abstract principles. They are steeped in particular contexts, shaped by our unique personal identities, charged with emotions, and informed by the specific relationships we hold dear.

Think about it: Your moral decisions are rarely just about applying a cold, impartial rule. They’re about who you are, what you value, whom you love, and the specific circumstances you find yourself in. Traditional moral philosophy, Williams contended, often tries to strip away these vital elements, hoping to find a “pure” moral agent beneath. But in doing so, it strips away the very humanity of the moral actor. It forgets that moral life is not a dispassionate calculation, but a deeply personal, often agonizing, journey.

To delve deeper into Williams’s challenge to conventional moral thinking, you might find this discussion illuminating:

Internal Reasons and Practical Deliberation

Instead of external, universal mandates, Williams emphasized “internal reasons for action.” These are reasons that genuinely connect with our existing motivations, desires, values, and commitments. We don’t act because some abstract principle commands it; we act because, in some profound sense, it makes sense to “us.”

Practical deliberation, then, isn’t about plugging a situation into a pre-existing moral algorithm. It’s about navigating our complex landscape of beliefs and desires, seeking a path that maintains our integrity and identity. When a moral theory demands that we act against our deepest internal reasons, it doesn’t make us “good”; it potentially alienates us from ourselves.

The Integrity of Self: Beyond the Moral Ledger

This brings us to one of Williams’s most powerful concepts: integrity. He argued that a moral theory that demands we sacrifice our core projects, values, and even our sense of self for the sake of some external moral imperative is deeply problematic. Imagine a situation where the “morally correct” action, according to a universal rule, would force you to abandon something central to your identity or betray a loved one. Is that truly a moral victory?

Williams suggested that we have a fundamental right to our own “ground projects” – the commitments that give our lives meaning. To insist that we should always be prepared to set these aside for the sake of an impartial, universal moral demand is, for Williams, to demand too much of human beings. It asks us to become mere conduits for moral rules, rather than agents with their own unique moral lives.

The most important thing about a person, from the point of view of morality, is whether he is good or bad. But it is not clear that this is the most important thing about a person, from the point of view of the person.

— Bernard Williams

The “Good Person” Illusion: A Dangerous Simplification

So, where does the “dangerous lie of being a “good person”“ come in? It’s in the very idea that there is a singular, objective, universally agreed-upon standard of “goodness” that we can all measure ourselves against. This illusion creates several traps:

Self-deception: We pretend our actions are driven by pure, impartial motives, even when our deeply personal desires and biases are at play.

Hypocrisy: We judge others by universal standards we secretly struggle to meet ourselves, or selectively apply principles to suit our convenience.

Denial of complexity: We shy away from the tragic choices inherent in moral life, where two deeply held values clash, and no “good” outcome is possible without loss.

Moral alienation: We adopt an external moral identity that doesn’t truly resonate with our internal values, leading to a sense of inauthenticity.

Perhaps the most profound moral act is not to conform to a universal code, but to bravely face the contradictions within ourselves.

Confronting Our Moral Messiness

Williams doesn’t offer a new moral system to replace the old. Instead, he offers a profound invitation: to be honest about the difficulties and uncertainties of moral life. He encourages us to embrace “thick” ethical concepts – like “courage,” “generosity,” “cruelty” – which are rich with contextual meaning and embody both descriptive content and evaluative force. These concepts are rooted in our shared forms of life, not in abstract, universal principles.

His work is a call to acknowledge:

The inevitability of moral conflicts and the absence of clear-cut answers.

The role of luck in our moral lives (moral luck).

The fact that sometimes, there is no “right” answer, only difficult choices with regrettable consequences.

Unlock deeper insights with a 10% discount on the annual plan.

Support thoughtful analysis and join a growing community of readers committed to understanding the world through philosophy and reason.

Conclusion

Bernard Williams reminds us that morality isn’t a science, and being a “good person” isn’t a simple checklist of universal virtues. It’s a complex, deeply personal journey fraught with internal conflicts, difficult choices, and the constant negotiation between who we are and what we believe is right.

The dangerous lie isn’t that we should strive for goodness, but that “goodness” can be found in a detached, impartial, universally applicable moral theory. True moral maturity, Williams suggests, lies not in shedding our personal identity to become a perfectly “moral agent,” but in bravely confronting the intricate, often messy, details of our own, unique moral lives.

It’s an uncomfortable truth, but perhaps a more authentic and ultimately more human one.

Video is unavailable unfortunately